My second semester at Texas State University began last January. I remember the morning of January 24 not because of my new classes but because of the frightening information that appeared on my phone.

My husband Igor Babkin was supposed to have arrived in Mexicali on the U.S.-Mexico border by the time I woke up, but his location on WhatsApp showed: ‘‘Last seen today at 09:22 a.m.”—on a remote desert highway connecting Tijuana to Mexicali.

We’d always share locations, lately so I’d know where to rescue him if it came to that. As a migrant waiting in northern Mexico for a U.S. Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) appointment to request asylum and cross into the United States, I knew Igor might leave for groceries one day and never come back.

The cartels or individual criminals are not the only things waiting asylum-seekers fear. The Instituto Nacional de Migración (INM) of Mexico raids hostels and apartments where migrants find shelter. They milk them for money or deport them.

I wondered: Why did it seem like Igor was on his way to Tijuana, when he was supposed to go the opposite way to await CBP in Mexicali, a less busy port of entry? Had Igor been abducted or arrested? Or was he already dead?

My husband and I are Russians who have actively protested President Vladimir Putin’s regime since 2017 and openly opposed the Ukraine war in 2022. Persecuted and unable to change anything as a children’s art teacher (my husband) and an independent journalist, we realized we were unwelcome in Russia, at least until the war ended. I applied for a graduate program in journalism at Texas State, so I could teach Russia’s new generation to tell propaganda from facts and prepare to restore democracy someday. They are our only hope since older citizens are mostly brainwashed.

In fall 2023, I received my U.S. student visa, but my husband didn’t get a visa to accompany me. So he stayed in Jakarta, Indonesia, which was a welcoming place for Russians and Ukrainians fleeing the war, offering visas to citizens of both countries upon arrival.

Prior to the war, Russians could fairly easily obtain U.S. visas, if they had a nice job or some real estate to demonstrate ties to their homeland. But U.S. consulates and embassy officials now seem to realize no job or mansion can keep a critically thinking young person tied to Russia. At first, Igor only sought a visa linked to mine, thinking that we’d eventually return. As conditions worsened, he decided to apply for asylum, which required travel to a U.S. port of entry.

He traveled alone to Mexico, and signed up via CBP One—the flawed app the U.S. government uses—for an appointment. He’d waited four months. What if I never saw him again?

I called Igor’s landlord in Mexico. (When you are an asylum-seeker waiting in Mexico, you befriend locals despite not knowing much Spanish or English.)

A Colombian with U.S. citizenship, the landlord said casually: “Oh, yeah, they were unlucky to meet the INM. The taxi driver got away with a bribe. They will pop out eventually.’’

What happened to Igor, January 24-27 of 2024, in his own words:

My friend’s 23-year-old brother Misha and I were taking an Uber when police and INM agents with automatic rifles stopped us at an improvised checkpoint. They checked our passports and told us to step out.

They probably didn’t like that Misha’s visa had expired. He had an Electronic Travel Authorization, used for citizens of Russia, Ukraine, and Turkey. Since this was Misha’s first overseas trip, he got less than a month’s authorization.

As an experienced 30-year-old traveler, I got the maximum 180 days to discover Mexico. Little did we know that appointment wait times for CBP would grow so dramatically that even six months would not be enough.

My stamp was valid until March 19, 2024, and I told INM officials they had no grounds to detain me. At different points, different people promised to check and release me. But no one did.

Using Google Translate, the INM agent in Tijuana had asked if we had an amparo—a legal document signed by a judge that can protect migrants in transit in Mexico. We didn’t.

After a day’s ride in a van with bars, we reached the Tijuana Estación Migratoria, where I was given my phone for a couple of minutes and called my wife, Liza. I hoped she could find an attorney to get an amparo. The thought of being deported after waiting 124 days for an appointment was unbearable.

INM officials told us to sign documents in Spanish or in English, though we didn’t understand. We later learned we’d agreed to a ban barring travel to any part of Mexico except Cancún.

The following morning, a lady from the United Nations arrived and told us in English that we couldn’t lawfully be detained in Mexico for more than 36 hours and we should still try to use the CBP app to get an appointment.

Next, we began a 56-hour nonstop journey on a smelly prison bus: Two Russians, some Indians, Chinese, and Hispanics. No one knew where we were going. They fed us, we went to the bathroom in the back, the drivers switched, but kept going. People with rifles accompanied us, so we rode without handcuffs.

After that call on January 24, 2024, I didn’t hear from Igor for three days. I didn’t eat or sleep, and spent time online asking for help and telling Igor’s story to warn other Russian travelers. I was crying a lot, not knowing what to do.

I was advised to pay $300 for a document called an amparo, so I contacted a Mexican attorney. The process was surprisingly rapid, but I then had to provide Igor and his friend with the documents.

Igor’s landlord visited the Tijuana detention center on Thursday only to find that no visitors were allowed. A transfer was already taking place. He and his employees shot a video of the bus for me. Finally, at 2 a.m., I got a call from a Russian social media account and suddenly I heard Igor’s tired voice.

The bus had dropped the migrants off at Monterrey, then they boarded a plane. For a while, they flew over the Gulf of Mexico and feared they were being deported to Cuba.

‘‘I don’t know where we are,” he said. “They just let us out in the middle of nowhere.” The INM had taken his money and phone, but somehow his friend Misha had kept his. Igor told me to stop worrying and go to bed. They planned to rent a room and decide next steps later.

GPS data showed me they were in Tabasco, near the Guatemalan border. I provided the amparo electronically, but I knew I needed to get them back to the U.S.-Mexico border for a chance at an appointment. (As our attorney in the States, Emma Tuohy, later explained: CBP One is a complicated lottery system and staying in line relies on access to a smart phone and the app.)

The next day, they bought bus tickets to Veracruz. We thought breaking up the journey to the U.S. border would make it safer. That was a mistake.

A little after the bus left Villahermosa, it stopped at another INM checkpoint. They were okay with Igor’s stamp, but agents detained Misha again—and they got off together. The bus left. They let the Mexican attorney know via phone that the immigration agents didn’t want to honor their amparos, and he contacted authorities to express concerns. By then, Misha had been taken away.

Igor had to walk for hours before getting a private driver through an app.

Upon release, Misha waited for another bus only to be taken into custody again after a three-minute ride. ‘‘They laughed at me, it was funny for them, can you understand?’’ he later told me by phone.

He spent a night hiding from gangs in the bushes.

Igor and Misha reunited and finally reached Veracruz on February 1, then Mexico City on February 11. They lost a couple of weeks deciding whether it was feasible to return to a “good” border in Baja California, next to a more welcoming Democratic state, instead of a city near Texas or Arizona. They also wanted to find out whether that “black mark” in Misha’s passport that created so many obstacles could be eliminated. Unfortunately, Misha couldn’t extend his tourist visa without leaving and staying elsewhere for six months.

In our intermittent phone conversations, I realized that Igor had changed after the abduction. He couldn’t sleep and always seemed irritated with me, especially when I couldn’t talk to him on the phone for hours without doing something else in the background. What freaked me out most was when he said he knew a way out of his always-bad mood: suicide.

From our first meeting in 2019, until he’d been abducted by Mexican authorities last year, Igor had always been my rock, supporting me in achieving things despite my chronic depression and ADHD. Now I had to become his support, which was no easy transition. I was alone in the United States and unable to tell my parents that Igor and I were apart, and that he had never gotten his visa.

Finding a psychiatrist in Mexico for a Russian asylum-seeker is like navigating seven circles of hell. No one wanted to deal with an interpreter. Some said they believed Igor was faking his depression in order to get preferential treatment from CBP. Then a miracle happened. Our new bilingual pen pal Bo (name changed for safety purposes) found a Russian-speaking psychiatrist in Mexico who referred us to a specialist and agreed to interpret the sessions over the phone.

Igor was diagnosed with PTSD and prescribed medications. After a week of taking them, he decided to risk traveling to the dangerous Mexican state of Tamaulipas, home of the Gulf Cartel, then surrendering to a CBP officer at the international bridge over the Rio Grande that connects Nuevo Progreso, Tamaulipas, with Progreso, Texas.

The thought of waiting 157 days in Mexico and then likely going to detention in the United States instead of being reunited with me, was killing him. He wanted to get it over with.

Igor and Misha reached Reynosa by plane on February 26. The INM showed them the amount they had to pay to exit the airport on a calculator as they did with all migrants, but Misha and Igor showed their amparos in response. That meant the travelers were recognized as asylum-seekers and didn’t have to do the typical role-playing that they previously had to in Tijuana. The game is, “We are tourists here.”

Upon reaching the bridge,40 kilometers (about 25 miles) east of Reynosa, Igor was told by cartel members that the crossing process was run by them. There are two lines—one for families with kids, who have priority, and one for singles. Igor and Misha became numbers 71 and 72 in the singles’ line.

But, that same day, the bridge was closed for any new migrant entries since it had reached maximum capacity. No new campers were allowed for a week.

It says a lot about how things were organized that cartel members were apparently the ones to close the bridge, though they collaborated with the INM. The cartel mostly communicated through a proxy they chose among the migrants.

For most of the time Igor and Misha were there, no one could leave the bridge even to buy food. They had to eat what they had brought or what church volunteers contributed. God bless those volunteers for those meals and for concerts they offered in the evenings. Everyone would forget their long wait to cross and become friends no matter what language they spoke.

Then, in late March, the migrants were punished (by the cartel), and the volunteers were no longer allowed access.

On April 5, after 39 days on the bridge—through hot days and heavy rains that swamped the tents, without a decent shower or way to wash clothes—Igor was finally admitted into the United States.

Everyone on the bridge regarded Igor as a veteran because he had waited the longest—he’d first requested an appointment 194 days prior on the CBP One app. He’d suffered serious harm to his mental health during that long wait. But Igor was still sent to the Port Isabel Detention Center. When talking to his Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officer, I was told that despite his multiple mental health issues and the terrible tooth pain he’d been suffering, a problem that later required surgery, he couldn’t be paroled because he was Russian. We needed to wait for a background check.

By 2023, more Russians had continued to emigrate, especially those who oppose the Ukraine war, and more were seeking asylum. Detentions of Russians, even those lucky enough to get CBP One appointments, intensified in the summer of 2023. To me, this was very frustrating because all Igor’s information had been on file in the CBP One app and he could have been checked long before.

Igor’s background check and the paperwork took another 28 days, short compared to the experience of some of our friends. On May 3, he was released. I bought him a bus ticket to San Antonio and went to meet him. After nearly a year apart, we were finally together in Texas.

ICE took his passport, and as an ID, he got a form with his picture and fingerprints. The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services denied his work authorization petition because he was not paroled for a significant public benefit or urgent humanitarian reasons. I thought: Isn’t his work creating paintings in support of Ukraine instead of fighting in Putin’s criminal war a public benefit? Isn’t his abduction for no reason in Mexico, leading to a mental illness, an urgent humanitarian need?

The federal government and the State of Texas might not be supportive. Yet we have been blessed by kind-hearted individuals here who have made us feel welcome as we wait for Igor’s immigration processing.

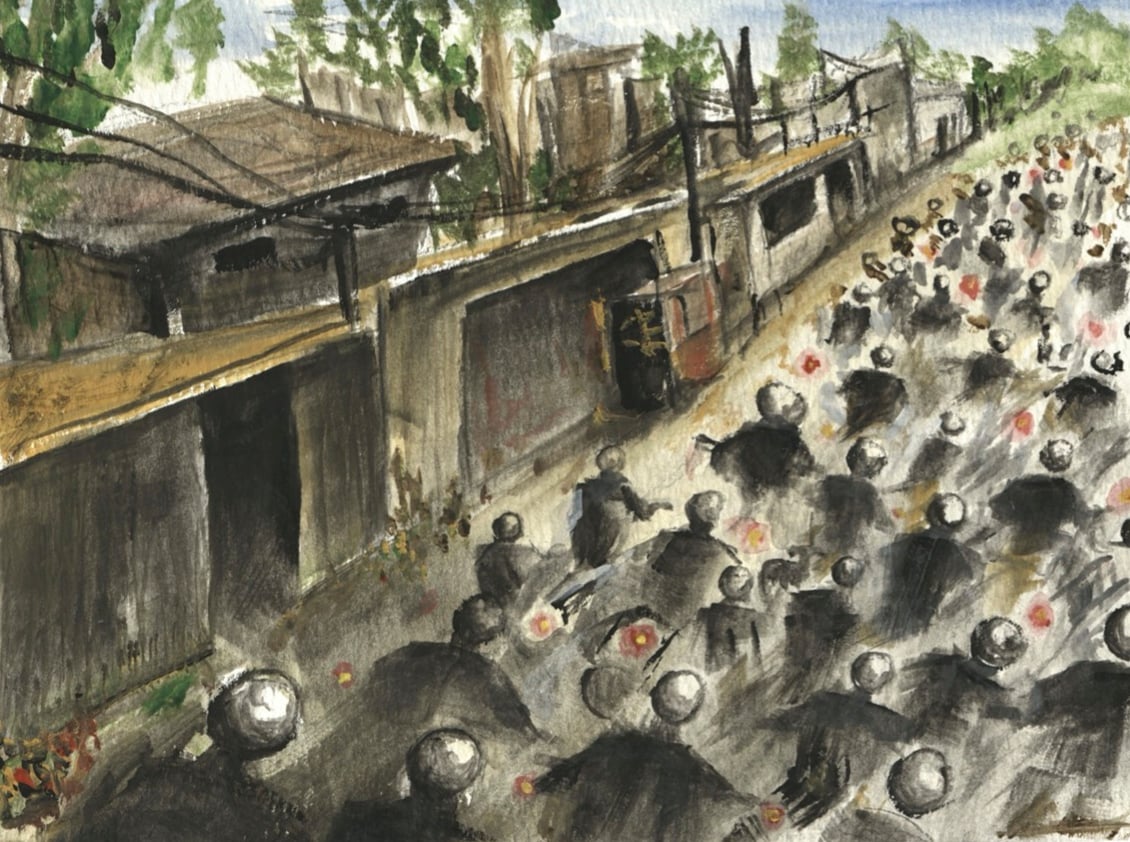

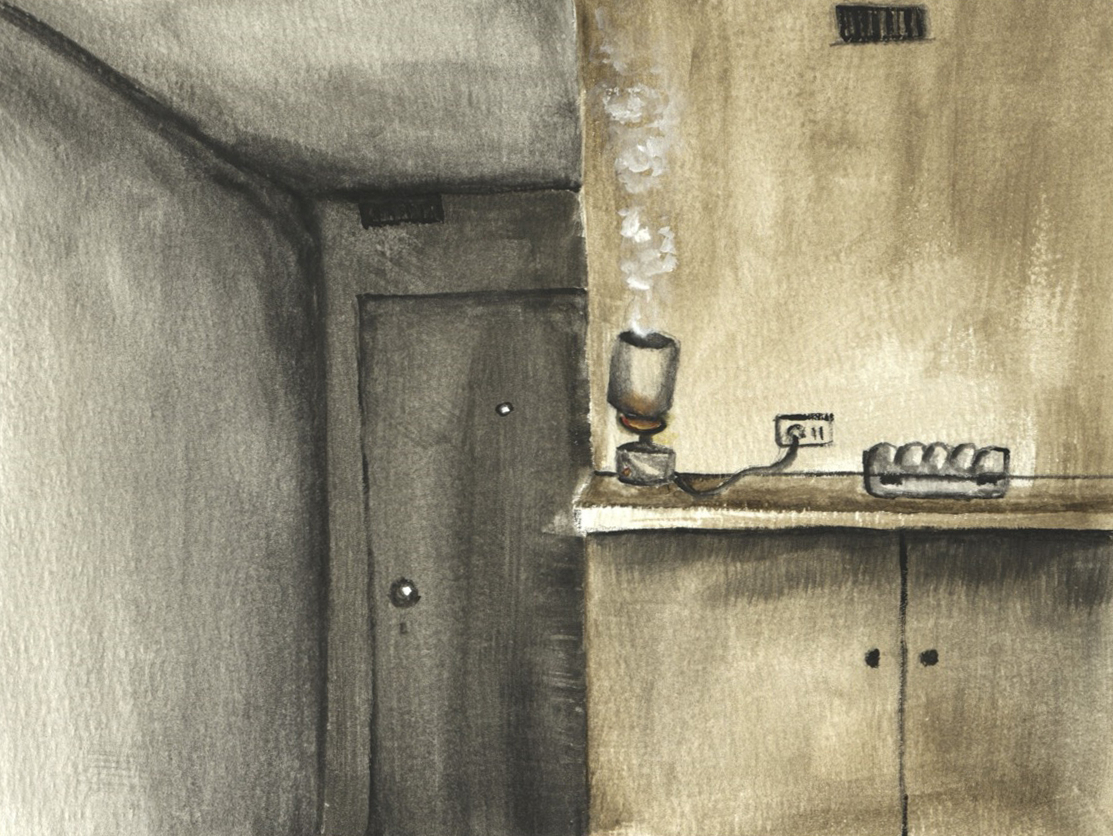

I am studying journalism, and Igor is learning English and continuing to create watercolors. He has joined the Wimberley and San Marcos Art Leagues to share his art and his story, and he also shares his work on his website.

Igor’s first defensive asylum hearing is scheduled for December 2026. After that, Igor will have a final hearing—which could be delayed months or years because of backlogs. Only then will a decision be made about his asylum application. In the meantime, he paints, since here he fears no persecution for his political pieces.