In June of 2000, the Texas Observer’s longest tenured editor, Lou Dubose, bade farewell with a note poetically titled “The Phones Were Ringing.” He recounted a time, three years prior, when a draft of a story—involving the Ku Klux Klan and a curious GOP voter registration strategy in a Texas border county—had gotten loose and was circulating like journalistic contraband. Calls were streaming into the Observer office as people sought out a copy of the still-unpublished issue. Then, with little ado about himself, Lou said goodbye: “It has been a wonderful thirteen years. It’s time to go.”

Since the late ’80s, Dubose had not only edited the Observer but written for the publication at a prodigious rate, with a special emphasis on Mexico and Latin America. He’d been “the heart of this office and the Observer,” wrote Michael King, his co-editor in the late ’90s. The following month, a reader from El Paso wrote in describing his reaction when he realized that the editorial about phones ringing was actually Dubose’s farewell: “‘Shit,’ I said out loud to my wife Lee, ‘Lou Dubose is leaving the Observer!’ But Lee was already asleep. Oh, well. I had my own little epiphany of sorrow.”

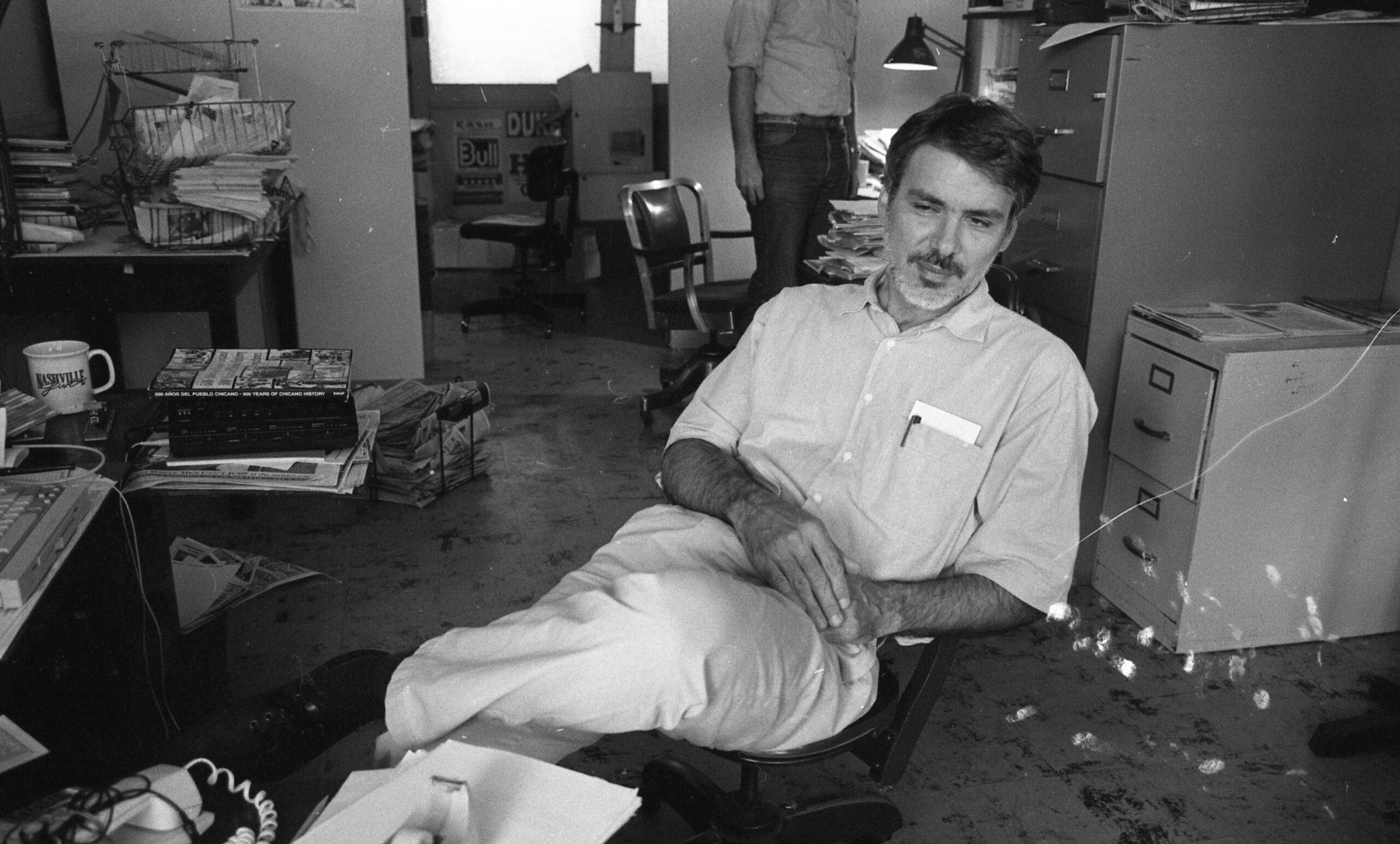

Between 2000 and 2007, Dubose went on to co-author some six books chronicling the George W. Bush administration, three co-written with Molly Ivins. He then spent about a decade editing The Washington Spectator, a D.C.-based progressive politics publication. Now 76, he splits most of his time between Hawaii and Spain and is working on a novel. In October, he was back in Austin for a bit, and the Observer caught up with him at the KOOP radio studio to chat about his career, the state of media, and the hazards of meeting book deadlines with Ivins.

TO: From your 13 years at the Observer, is there one story that still jumps out that you remember as the most meaningful for you?

Oh, there’s so many. You know, one of the most meaningful stories I did was a story that documented a Republican voting scam that was out in Val Verde County, in which the Republican Party was pitching registration to former residents of Val Verde County who were at the Air Force base. And they were voting from all over the world, some of them thinking that they could maintain their Texas residency and therefore not pay income tax where they lived. But they had registered thousands of military voters, and so that story in particular—when you think of what’s going on today—and it ended up with a Klansman on the cover, a former Klansman who was running for county commissioner in Val Verde County.

This was the story referenced in your farewell editorial. You wrote that this was an example of local media in Texas not being able to cover what the Observer could.

The same can be said about Nate Blakeslee’s extraordinary Tulia story. I mean, no one got it up there, nor did any of the other big dailies to whom it was probably pitched. I think that has always been an important function of the Observer. There are local stories where local newspapers would not touch them—and 1733757668 they’re also so under-resourced.

In the same farewell issue, your co-editor Michael King wrote that you “presided over the Observer longer than any of the other storied editors who have led the legendary staffbox since 1954.” I’ve found myself the newly minted editor-in-chief, so can you tell me your secret?

Yes. Be fortunate. You know, be fortunate enough to recruit, which the Observer is doing now, great talent. We struggled for my first seven or eight years, and Michael came on and Michael was a really talented editor. Then, when someone like Karen Olsson walks in the door and says, “I’d like to be an intern.” And you look at her and she has a math degree from Harvard, and you think, well, this is interesting. Then someone like Nate walks in, and Nate really insinuated himself into a job by being a volunteer freelancer using our office and then stayed. Two extraordinary talents. I mean, two of the finest writers in Texas to this day. That was the secret: The Observer attracts talent, dedicated talent committed to progressive journalism.

Around the time you left the Observer, you started co-writing a string of books with Molly and others about the Bush administration.

Yes, and here is the Observer story that has to do with my writing books. Molly invited me to San Antonio to meet a prominent ACLU lawyer, and we were driving over to San Antonio, and she asked me if I would be interested in collaborating on a book with her, and I mean, are you kidding? With Molly, writing a book. So that was Shrub. And the proceeds from that book went to the Observer. I got $25,000 because I couldn’t do it for nothing, but it generated hundreds of thousands of dollars for the Observer.

Thank you.

No, don’t thank me; it was Molly’s decision!

Thank Molly. What was she like as a co-author?

Oh, Molly. Kaye Northcott will tell you that Molly is a woman who never met a deadline. I mean, she met a deadline, but the deadline was on the hour or maybe a couple of hours later. So there was a time when Random House required printed paper rather than an electronic file. So I swear I would run to the car and race into FedEx to get the copy to Random House by their deadline. She always took it right to the end, but she was great fun to work with, and, you know, she had a concept of how a story should be told, and she loved it.

The Observer has always had this role where it’s independent journalism, and it’s also in relationship with the broader progressive movement in Texas. But the state has proven so resistant to change. From where you sit: Do you still see a role for journalism like the Observer does, and do you see a path to change in this state?

Yes and no. I think the Observer is critically important. When you consider the reduction in the capitol staff of most of the big dailies, who else will write and provide the sort of critical coverage that the Observer does if it disappears? So I really do see a more essential role now. And if there is a change, I think the Observer will have a place in bringing that change about.

But the path to change—it’s dark. It’s not entirely hopeless, but there’s not a lot of hope there at the moment. Would you agree?

I mean, I would have never thought when I moved to Texas in 2015 that Ken Paxton in particular would still be in office.

Astounding. Just astounding.

The thing I try to tell people is that what we do doesn’t change that much depending on the political climate, because we do a lot of investigative journalism. There’s always investigative journalism to be done. We try to keep our moral compass and our wits about us. And, maybe one day, you know, you can’t lose hope.

Right.

Well, thank you, Lou, I think—

One more story about Molly.

Yes.

When she was dying, the week before she died, she was at Seton. I went to see her. She was semi-conscious. I had been working on the book we were doing then, which was published after she died, Bill of Wrongs. I went to the hospital. She woke up and saw me. She smiled, and she gestured for me to get close to her because her voice was so low. I thought this was going to be the moment when she would say goodbye and we’d been through a lot together and how much she appreciated me. And she said, “Call the Observer, make them get the names of the 10 Democrats who signed pledge cards for Tom Craddick.” And that was her. That was Molly. So I’ll close with that.

This interview, which is part of the Observer’s 70th anniversary coverage, has been edited for length and clarity. Support for our 70th anniversary interview series has been provided by KOOP Radio in Austin, which permitted its studios to be used for recordings.