I pulled up to the train depot in the East Texas city of Palestine, $220 poorer after falling into a speed trap in the nearby town of Oakwood. The indifferent officer had given me my first-ever speeding ticket.

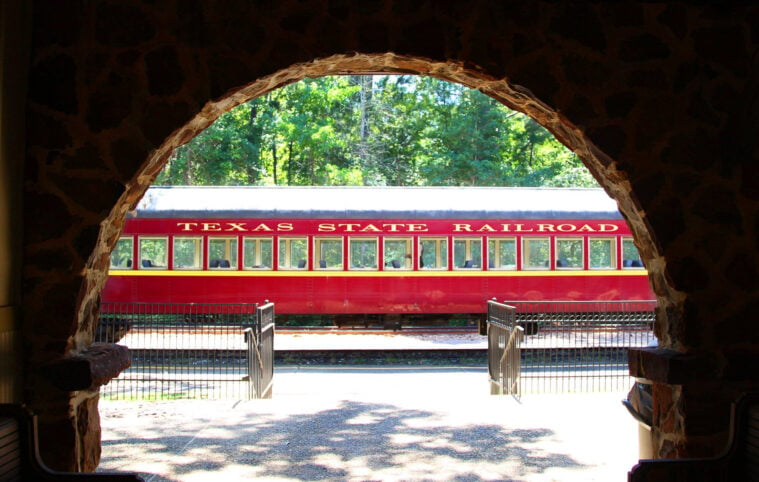

Thankfully, I was scheduled to be a passenger, not a driver, for the next four hours. I arrived early for my historical train ride through the Piney Woods, and there were already scores of passengers lounging at picnic tables and inspecting the behemoth train cars that stood sentinel over the Victorian-style depot.

The Palestine Rail Depot is the western terminus of a line that once connected to the newly constructed Rusk Penitentiary at the turn of the 20th century. The state’s second prison did more than relieve crowding at the flagship facility in Huntsville—it provided a captive workforce to drive the area’s burgeoning iron ore industry. The 25-mile rail line between Rusk and Palestine was largely staffed by incarcerated Texans during its heyday.

After Rusk closed in 1917—iron ore wasn’t gold after all—private companies leased the line before it was granted to the Texas Department of Parks and Wildlife in 1972. To mark the country’s bicentennial four years later, the line reopened as a historical state park. The rails no longer carry prisoners, iron ore, or timber. Now, visitors from all corners of the state come to take a ride on what became, in 2003, the official State Railroad of Texas. Every governor since Dolph Briscoe—who joined the inaugural passenger trip on America’s 200th birthday—has ridden this line.

David and Miranda, a well-dressed Austin-area couple lingering beside the train when I arrived, had their own cause for celebration: They’d stopped off during a road trip to mark their 17th wedding anniversary. Nearby, a group of six graying friends from across Texas was holding a reunion of sorts, reminiscing about previous trips on the very same train. Cary, a 52-year-old model train collector, was celebrating his recent birthday with his wife, Chanda, who bought their tickets.

When our scheduled departure time arrived, I walked up the steep, narrow steps to the top of the glass-topped dome car. There were tables and booth seating, well-suited for groups of four. My seat was at the very back of the car, marked by a single water bottle across from two more as yet unclaimed. An unfortunate couple would be stuck sitting across from a lone traveler with a voice recorder—hardly what they expected, but over several hours of conversation in close quarters, I learned my seatmates had never met a stranger.

My travel companions were James, a retired Dallas police officer with close-cropped white hair obscured by a camo visor, and his wife Lauri, a cancer survivor with a dark brown bob and a bright smile. The parents of two grown boys, the couple had become experienced day-trippers; between them, they had a near encyclopedic knowledge of the best unsung tourist attractions in Texas.

They’d wanted to go on this train ride for decades, and with Lauri’s birthday coming up, they decided it was finally time. Five years ago, James had left the police force after a quarter-century’s service, driven out by a dwindling pension fund and ballooning insurance costs that coincided with Lauri’s cancer diagnosis. Now, he drives a school bus in Forney, which he refers to as his “old man job.”

As we talked, oaks blurred into pines outside our window, and cedar elms cast large, round shadows on the grass below. We passed through Maydelle, where we waved to a pickup that waited at the tracks for us to pass, kids spilling out of its windows and standing on tip-toes in the bed to greet us on our short passage through their town.

We disembarked at the Rusk Rail Depot, where we ate picnic lunches by the still waters of Cherokee Lake. Train staff had told us we could swim if we wanted, but the train might not wait for us if we weren’t out in time. That, and the signs informing us that here, there be alligators, was enough to keep everyone dry.

The return trip from Rusk to Palestine seemed to go by at double speed. As we pulled into the depot, I exchanged email addresses with James and Lauri. I had the nostalgic feeling of a teenager at the end of summer camp—the result of time spent in forced proximity, time with nothing to do but become a temporary community. We enjoyed the journey—and, perhaps my favorite feature of rail travel, there was no risk of a speeding ticket.