As President-elect Donald Trump gears up for his second term in January, things might appear bleak for those who want to see the United States tackle climate change. Trump has promised to expand fossil fuel production and undo much of President Joe Biden’s climate agenda, saying he would roll back environmental regulations, cut federal support for clean energy, and withdraw from the Paris climate agreement — again.

But a certain brand of Republican still hopes to push the incoming administration to take on climate change, the “America First” way. In a statement congratulating Trump on his victory last week, the American Conservation Coalition, a Washington, D.C.-based group trying to build a conservative environmental movement, laid out the case for a cleaner future by emphasizing the economy, innovation, and competition with China. “In the 20th century, America put a man on the moon and the internet in the palm of our hands,” the group’s statement says. “Now, we will build a new era of American industry and win the clean energy arms race.”

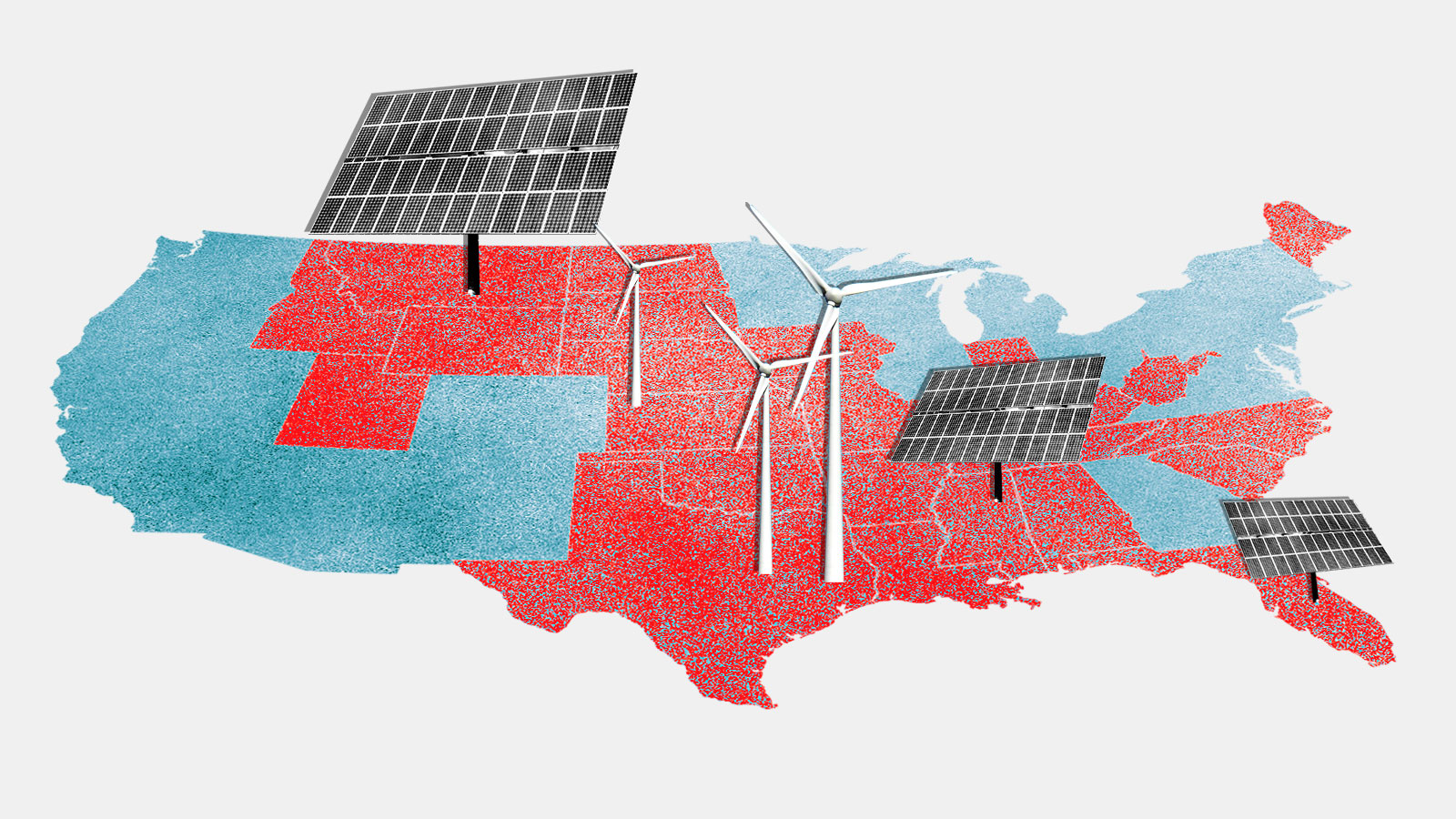

The lines read like they came from a parallel universe where Republicans, rather than Democrats, had prioritized taking on climate change. In reality, the belief that people are driving global warming is one of the issues where the partisan gap has widened the most over the last two decades, and Republican politicians regularly attack climate solutions like wind and solar power.

But in recent years, behind the scenes, congressional Republicans have been talking to one another about how their party might be able to address rising carbon emissions. Even red states like Arkansas and Utah have quietly passed bipartisan policies that help the climate, though they’re often less ambitious than what Democrats propose and are rarely promoted as “climate action.”

“I don’t think progress will stop,” said Renae Marshall, who researches bipartisan cooperation on climate change at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “I think it’ll just be harder.”

Republicans aren’t a monolith, as 54 percent of them say they support the U.S. participating in international efforts to reduce the effects of climate change, and 60 and 70 percent, respectively, say they want more wind and solar farms. Younger Republicans in particular are also less supportive of expanding fossil fuels, Pew Research surveys show.

“Climate change is less polarizing than we think,” said Matthew Burgess, an environmental economist at the University of Wyoming. “Let’s notice that, and say that out loud, and work with that.”

For an example of what’s politically possible, take the Energy Act of 2020, signed by Trump during the last year of his presidency. The law, which passed through a Democratic House and a Republican Senate, included investments in renewables, energy efficiency, carbon capture, and nuclear energy. It also phased down the production of hydrofluorocarbons, so-called super-pollutants that are thousands of times more potent than carbon dioxide at warming the atmosphere.

Now with both the Senate and the House of Representatives in their control, Republicans see an opportunity to reform the permitting process for new energy projects. The idea is to make it faster and easier to approve both fossil fuel projects as well as clean energy ones. The United States’ recent surge in oil and gas development has already imperiled the world’s climate goals, so support for loosening rules for permits could backfire, but the American Conservation Coalition sees it as essential.

“During a second Trump presidency, we can expect robust permitting reform efforts, making it possible to build again in America, paired with an energy dominance agenda that will put American energy first on the world stage and reduce global emissions,” said Danielle B. Franz, the coalition’s CEO, in a statement to Grist. “We advise those in the climate community to approach the second administration with good faith over skepticism.”

Even if progress stalls at the federal level, precedent suggests that Republican-led states might pass energy policies that reduce emissions. During the same era Trump was last in office, from 2015 to 2020, Arkansas, South Carolina, and Utah enacted legislation to pave the way for expanding solar and wind power. Of the roughly 400 state-level bills to reduce carbon emissions from that time period, 28 percent of them passed through Republican-controlled legislatures, according to Marshall and Burgess’ research.

Their analysis showed that these laws, which carried bipartisan support, had some key things in common. They tended to expand choices for energy rather than restricting them — think of removing red tape for solar projects, as opposed to banning new gas stoves. The bills that got bipartisan support were also more likely to emphasize the concept of “economic justice,” meaning that they aimed to help lower-income people, rather than use language related to race or gender. “The best way to depolarize it is to get it as far away from the culture wars as you can,” Burgess said.

The rare Republican politicians who talk openly about climate change often distance themselves from their Democratic counterparts. “I think anybody that’s had a chance to hear me talk about climate understands that I do it from a very conservative perspective, so much so that the left would say, ‘You’re not serious about it,’” said Representative John Curtis from Utah, who was just elected to the Senate, in a conversation with reporters last month.

Curtis started the Conservative Climate Caucus in 2021 to get House Republicans talking to each other about climate change and thinking through what a conservative-friendly approach to the problem might look like, with the goal of offering alternatives to “radical progressive climate proposals that would hurt our economy, American workers, and national security,” according to the group’s site. The caucus now has 85 members.

“It kind of serves as this, like, glue, this social capital glue, that helps them talk about climate together when they might not have otherwise,” said Marshall, who is keeping an eye on the caucus. Liberals sometimes question the usefulness of talking to Republicans about climate change, she said, but she believes bipartisanship is necessary for long-term progress.

Even with Trump’s expected onslaught on regulations, Burgess expects U.S. greenhouse gas emissions to continue to steadily decline in the coming years, since states and businesses are doing a lot to cut carbon emissions. He also thinks that the climate policies Congress passed during the Biden era might be protected: They either passed with Republican support, or, in the case of the Inflation Reduction Act, which invests hundreds of billions of dollars in green technologies, mostly benefit Republican districts. Biden’s climate policies, Burgess said, “are almost perfectly designed to be bipartisan” — so it’s possible they might survive a second Trump administration mostly intact, in spite of all the bluster.