Oct. 31, 1950

Earl Lloyd became the first of three Black players (Chuck Cooper and Nat Clifton were the other two) in the National Basketball Association, paving the way for other African Americans who would follow.

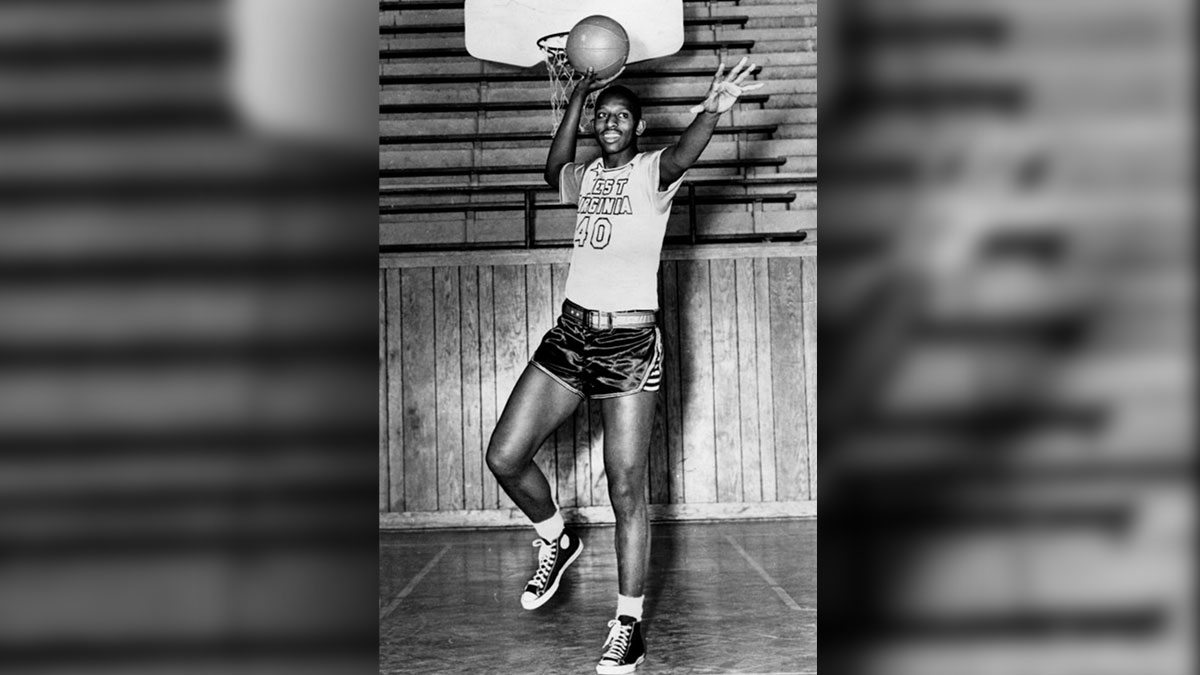

A native of Alexandria, Virginia, the 6-foot-6 phenom became a defensive star at Parker-Grey High School, nicknamed “Moon Fixer.” He received a scholarship from West Virginia State, whom he led to two tournament championships. He became an All-American, and in 1947-48, his Yellow Jackets were the only undefeated team in the nation.

Nicknamed “The Big Cat,” he played his first game on Halloween. “The game was totally, unequivocally uneventful except for the date — Oct. 31,” he recalled later. “Maybe they thought I was a goblin or something.”

The Korean War interrupted his career before he returned to the hardwood, first with the Harlem Globetrotters and then back with the NBA. In 1955, he helped the Syracuse Nationals (now the Philadelphia 76ers) defeat the Fort Wayne Pistons for the NBA Championship.

He and Jim Tucker were the first African Americans to play on an NBA championship team. As a player, he endured prejudice, both in the arena and out, one Indiana fan spitting on him. In 1968, he became the NBA’s first Black assistant coach with the Detroit Pistons and became head coach in the 1971-72 season. He later worked for the public schools in Detroit, running programs that taught job skills to underprivileged children.

In 2003, the Basketball Hall of Fame inducted him, recognizing his contributions to the sport. “It’s easy to be successful when you’re surrounded by the greatest,” he said.

Four years later, his hometown of Alexandria named its newly constructed basketball court in his honor. The year he died, 2015, he became one of eight Virginians that the Library of Virginia named as the “Strong Men & Women in Virginia History.”

The NBA honored Lloyd for his work as a pioneer, but he remained humble. “I don’t think my situation was anything like Jackie Robinson’s,” he said. “I remember in Fort Wayne, Indiana, we stayed at a hotel where they let me sleep, but they wouldn’t let me eat. … Did it make me bitter? No. If you let yourself become bitter, it will eat away at you inside. If adversity doesn’t kill you, it makes you a better person.”