PIERRE, S.D. (KELO) — A state circuit judge could decide later this week whether the woman accused of stealing more than $1.7 million from the South Dakota Department of Social Services over a period of 14 years while she worked in the child-protection office can have a forensic accountant and a mental health professional help in her defense.

Her court-appointed attorney, Timothy Whalen, claims in a recent court filing that the mental-health professional is necessary because there is evidence that the 68-year-old defendant, Lonna Carroll, “may suffer from an obsessive-compulsive disorder known as Hoarder Disorder.” He has also requested a continuance in the case because, he says, discovery issues have been in litigation.

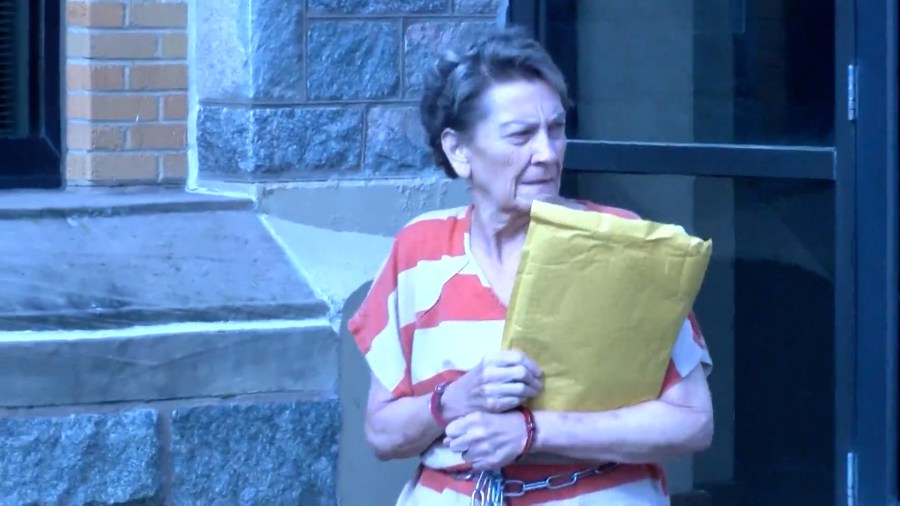

Carroll was arrested on July 17 on charges of aggravated grand theft over $500,000, which is a Class 2 felony punishable by up to 25 years in state prison and a fine up to $50,000; and of aggravated grand theft over $100,000, a Class 3 felony punishable by up to 15 years and a $30,000 fine.

Her arrest came after DSS officials discovered suspicious activities and reported them to the state Division of Criminal Investigation. The state Department of Legislative Audit was quickly brought in to conduct a special review.

At her August 27 arraignment, Carroll pleaded not-guilty to both charges. Circuit Judge Christie Klinger then scheduled a three-day jury trial to begin on December 4. However, on October 1, Carroll’s attorney filed several requests, including one seeking a continuance.

“Due to the discovery issues, the Defendant as of the date hereof has not been provided any discovery and has not had an opportunity to see any of the state’s evidence and investigative materials,” he stated.

Judge Klinger has now set a date to consider those motions. The hearing will be held on the morning of Friday, November 1, one month after Carroll’s attorney first made the requests.

Nolan Welker, the state assistant attorney general prosecuting the case against Carroll, says the state is willing to allow the forensic accountant, with the cost capped at $5,000.

Hughes County is already paying the cost for Carroll’s defense. That’s because Circuit Judge Margo Northrup ordered on July 25 that Carroll was indigent, meaning that Carroll, who had allegedly stolen hundreds of thousands of dollars, couldn’t now afford to hire an attorney to defend her.

Welker however is resisting Carroll’s request for the mental health professional, calling the testimony “unreasonable and unnecessary.” He argued in an October 2 filing that Carroll, who earlier declared to the court that she is not-guilty, has not “pled properly to raise what appears to amount to an insanity defense.” Carroll would have needed to plead “not guilty and not guilty by reason of insanity,” according to Welker.

The prosecution is likewise resisting the continuance request. Welker argued in a separate October 2 filing that the “defense counsel has had the discovery material for approximately one month and, at the time of this filing, over two months remain until trial for Defendant and defense counsel to continue preparations. The Defendant herself now has access to the discovery material while being held on bond.”

Welker stated a continuance would result in prejudice to the state’s prosecution.

“Witness memories fade over time. The Indictment alleges that Defendant’s criminal actions go back at least fourteen years. Delaying this trail without adequate reason merely risks the loss of relevant testimony without any clear benefit to the Defendant’s case,” he wrote.

Judge Klinger on September 9 had allowed Carroll’s defense to hire a private investigator, Laura Zylstra of Aberdeen, to review the discovery materials, with a cap of $3,500, for which Hughes County is responsible. “The Defendant is indigent and cannot afford to retain an investigator to assist her in this matter,” Carroll’s lawyer wrote at the time.

The first steps of Carroll’s legal process were handled by Judge Northrup, including consideration of Carroll’s application for court-appointed counsel.

Carroll stated on the application form that she was retired. On the right side, she printed, “Receive Retirement — But accts are suspended.” She listed $3,051 cash in a bank; $50,000 in investments; $165,000 as the value of the house in Algona, Iowa, where she was living at the time of her arrest; a “Chevy Blazer being paid on”; $10,000 in household goods; and monthly expenses of $1,700.

Judge Northrup found Carroll qualified as indigent and appointed Whalen, whose legal practice is based in Lake Andes, South Dakota. Judge Northrup also set Carroll’s bond at $50,000 cash and ordered that Carroll make “no purchases over $2,500 unless approved by court through counsel.”

On the bond form, Judge Northrup listed various factors that she had considered in setting the bond. She then noted, “Pursuant to SDCL 23A-43-21, the Court finds that there has been shown a material breach of a condition of release without good cause which requires that the Defendant remain in custody until this matter is discharged by due course of law.” The form didn’t specifically identify the breach.

Judge Northrup further found that “Release on PR (personal recognizance) bond will not reasonably assure the appearance of the defendant as required” and that “Defendant does pose a danger to any person or the community.”

Whalen cited the requests for a forensic accountant and a mental health professional as reasons supporting the request for a continuance, stating “there is not sufficient time” for them to assist in Carroll’s defense before the December 4 start of her trial.

In his motion seeking the appointment of a mental health professional, Whalen stated, “The services of a psychiatrist or psychologist are essential to the Defendant’s right to present a defense in this matter and to assure that she receives a fair and impartial trial.”

Whalen suggested a $10,000 cap on the cost of the mental health professional’s services. Assistant attorney general Welker resisted the appointment. “It appears that Defendant may be seeking an expert to testify that Defendant has a compulsion which she may have satisfied by committing the alleged thefts in this case,” Welker stated. “If that is Defendant’s theory for retaining an expert, his request is not reasonable and such an expert is not necessary or appropriate for multiple reasons.”

Welker laid out several reasons. “Defendant has not specifically alleged, and the State has not seen any evidence to support, that Defendant did not know the wrongfulness of her actions.” He added, “Even if Defendant intends to argue a diminished capacity defense, the requested expert seems to only bolster the state’s case. Such a request from Defendant is unreasonable and should be denied.”

Welker also pointed out that the allegation by Carroll’s attorney regarding Hoarding Disorder “suggests that Defendant’s motion may be in anticipation of an insanity defense.”

Welker explained, “If insanity is to be raised, examination by a mental health expert must specifically be by psychiatrist and not psychologist.” He then noted that Whalen in an email to the court “indicated that he would use a specific psychologist as his expert. A psychologist would be statutorily inappropriate for the testimony it appears Defendant may be seeking.”

Welker said that “an insanity defense has no basis in the facts or the law” in the case. “Defendant’s alleged criminal conduct happened regularly over the course of multiple years alleged in the Indictment.” He said South Dakota law defines insanity as “the condition of a person temporarily or partially deprived of reason, … but not including an abnormality manifested only by repeated unlawful or antisocial behavior.”

“Based on that definition,” Welker stated, “even if Hoarding Disorder can explain one instance of theft as part of the aggregation during the course of years in the Indictment, such a defense cannot amount to a legal insanity defense in Defendant’s charged and aggregated criminal theft.”

On October 2, the assistant attorney general also gave the court notice of the state’s intent to file direct evidence that is admissible under the “other acts” provision of South Dakota criminal law known as 404(b) for the “purpose, such as proving motive, opportunity, intent, preparation, plan, knowledge, identity, absence of mistake, or lack of accident.”

The 404(b) filing included claims by the prosecution about Carroll’s employment in the child-protection office of the state Department of Social Services.

“While working as a ‘Program Assistant’ for DSS, Defendant was able to use DSS’s internal processes to make fraudulent expenditure requests for children in DSS custody. Although these expenditure requests normally require various levels of DSS approval before payment is dispersed, Defendant was somehow able to override the required approvals and avoid proper oversight.

“Defendant used a procedure with her expenditure requests that was not followed by any other DSS employees,” the filing continued. “Further, once the funds for the expenditure requests were dispersed, Defendant appropriated those funds for her own personal use instead of leaving the funds in dedicated savings accounts for the child designated in the expenditure request. It is through this process that Defendant was able to acquire and thereby take, or exercise unauthorized control over, the money which the state is alleging Defendant stole in this case.”

Carroll’s final hourly wage when she retired was $21.09, according to a state listing. Her last known address in Pierre was an apartment on the city’s north side.

The 404(b) filing goes on to list various types of evidence that the prosecution seeks to present against Carroll:

“The Defendant’s legitimate known salaries, wages and other income.

“That Defendant appeared, both in financial statements and to others, to be living beyond the means of her legitimate known salaries, wages, and other income.

“That the Defendant frequented or excessively frequented retail stores and establishments in Pierre and elsewhere, including online.

“That at least one retail clothing boutique in or around Pierre would regularly call Defendant to let Defendant know that the boutique had received a new shipment of clothes in.

“That the Defendant’s apparent clothing and food purchases appeared to the Defendant’s co-workers to be beyond what Defendant would have been able to afford on her known salaries, wages, and other income.

“That Defendant was known to her DSS co-workers as an excellent dresser or that she never wore the same outfit or clothing twice to work and that Defendant had an abnormal amount of different clothes and shoes.

“That the Defendant possessed or drove vehicles and made other large asset purchases for herself or others that may have been outside the means of her legitimate known salaries, wages, or other income.

“That the Defendant rented or utilized multiple storage units in Pierre or elsewhere, and any testimony or evidence regarding the contents found in those storage units which relate to Defendant’s spending or financial behavior.”

Prosecutors also want to introduce 404(b) evidence and testimony regarding Carroll’s personal and interpersonal behavior at work and elsewhere during the 14-year period covered by the indictment, including:

“That the Defendant would refuse to take direction from supervisors and if any person attempted to provide oversight or direction to the Defendant, Defendant would often refuse to talk to that person for multiple days.

“That the Defendant became combative with her coworkers and supervisors at work when DSS requested Defendant cross-train another employee on Defendant’s job duties and role within DSS.

“That the Defendant became combative with her coworkers and supervisors at work when DSS attempted to alter, modify or improve existing supervisory and practical structures and procedures including regarding DSS expenditure request software and procedures surrounding Defendant.

“That the Defendant retired from her position at DSS shortly after cross-trainings and other procedural and oversight changes became mandatory implementation at DSS.

“That the Defendant did not leave behind a ‘Legacy File’ when she retired as all employees are required to do. Legacy Files are meant to include a description of an employee’s job duties and how to perform them.”

The prosecution’s filing argues that the 404(b) evidence are relevant because it may show motive for Carroll’s alleged acts and may show Carroll’s “willingness to allow people in her professional circle to get close enough to uncover her crimes or end her ability to continue them” as well as why she chose to retire.

Two other former state government employees from the Pierre area await arraignment on criminal charges regarding motor-vehicle titles in the South Dakota Department of Revenue. Lynne Hunsley and Danielle Degenstein currently are scheduled to be arraigned on November 12.

The Legislature’s Executive Board on Tuesday authorized the Government Operations and Audit Committee to issue subpoenas for Revenue Secretary Michael Houdyshell and motor-vehicles division director Rosa Yaeger.