If you don’t like the weather, wait five minutes. It’s an old joke penned by the celebrated writer Mark Twain, who lived in Nevada in the mid-1800s, and it continues to ring true in the Silver State.

In 2024, Northern Nevada was under a blizzard warning in the spring and Southern Nevada shattered heat records in the summer. By fall, most of the state was in some level of drought — despite the 2024 water year wrapping up Sept. 30 with mostly normal numbers.

Now, water scientists and wildfire experts are looking for signs of what 2025 might hold for the state but it’s largely still up in the air — according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center, the region has an equal chance of having above, near or below-normal precipitation in 2025.

“It’s still very uncertain,” said Dan McEvoy, a climate researcher at the Desert Research Institute’s Western Regional Climate Center. “There’s a lot of data gaps in Nevada at the end of the day.”

Here’s a breakdown of how 2024’s water year went, what to expect for the coming winter, and an update on wildfire risk in the state.

An abnormally normal water year

Water years are measured from Oct. 1 to Sept. 30, a timeline that, in the West, coincides with the start of the rainy and snowy season, followed by the melting of the snowpack and a drying period in the summer.

Despite a dry start to the 2024 water year, late-season storms in February and March left most of Nevada and California with near-normal precipitation.

Atmospheric rivers — rivers in the sky that drop large volumes of rain and snow when they hit land — picked up in January, February and March and included a four-day blizzard in early March that dropped as much as 7 feet of snow in some areas. With the late-season storms, Nevada ended the water year close to normal — the state averaged 70 percent to 130 percent of normal precipitation.

“It was unusual how close to average everything was,” McEvoy said. “We never seem to end up right at average.”

With memories of last season’s Miracle March storm and the big winter of 2023, some Tahoe ski resorts are predicting they will open in early to mid-November — despite temperatures that, to this point, have been largely balmy and dry.

It’s not just Tahoe skiers who look forward to big snow years, though. Nevada ranchers and farmers rely on snowfall for everything from irrigation to better pasture conditions for livestock.

But NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center’s forecast through January doesn’t offer much insight into the coming year.

“There are some signals to suggest closer to normal precipitation. But one storm can make or break the situation, especially across much of Nevada,” said state climatologist Baker Perry.

A La Niña watch is in place, which could lead to warmer and drier conditions in Southern Nevada, although dry conditions are already in place for many Nevadans.

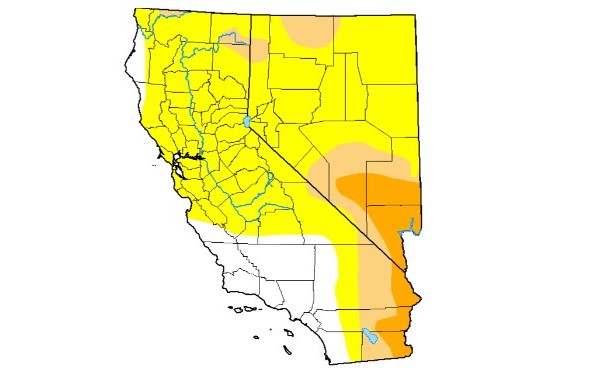

More of the state is in some type of drought condition than a year ago this month, with roughly 2.1 million Nevadans living in areas inflicted by drought, partially brought on by a lack of summer monsoons.

“This year, in Southern Nevada, when you expected to get moisture from the summer monsoon, it was extra dry,” McEvoy said.

In June, less than 2 percent of California and Nevada were considered to be in drought or abnormally dry. By Oct. 1, all of Nevada was considered afflicted by some type of drought conditions. Portions of Lincoln and Nye counties and almost all of Clark County are considered in severe drought.

As Clark County remains dry, so, too, does the reservoir it pulls most of its water from. Lake Mead on the Colorado River remains 33 percent full. Earlier this year, the federal government shifted Nevada, which pulls water from Lake Mead for the Las Vegas area — from a tier two water shortage to a tier one shortage. The shift is a less restrictive level of conservation, but one that still equates to a reduction of 21,000 acre-feet water for Southern Nevada, or 7 percent of its standard allocation of 300,000 acre-feet of Colorado River water.

An acre-foot is enough to cover 1 acre of land in 12 inches of water. Through conservation efforts, Southern Nevada uses less than its annual allocation each year.

That tier one designation will continue into the 2025 water year.

Wildfire danger remains high

This year, wildfire danger has remained high, an effect of the summer’s extreme heat.

As of Oct. 24, 742 fires had burned more than 99,000 acres statewide. The human-caused Castle Ridge Fire earlier this month in Elko County accounted for about a quarter of that acreage.

More than half of the fires were caused by humans and about 70 percent of all acreage burned thus far was caused by human-sparked wildfires, according to State Firewarden Kacey KC.

Last year, following the extremely heavy snow year of 2023, just 1,300 acres burned in Nevada. An average of about 500,000 acres burn each year in the state, KC said — a combination of extremely low burn years such as 2023 and devastating fires such as the 2018 Martin Fire near Winnemucca that burned about 1 million acres.

And despite the cooler temperatures, wildfire season is still active statewide, KC said.

“We feel different in the fall, but the vegetation hasn’t recovered. It’s [almost] as dry as it was in August,” she said, noting that some of Northern Nevada’s most devastating wildfires near urban areas occur in late fall and early winter.

“We are still in extreme to moderate [wildfire danger] across the state … until we get a really good wetting system — rain or snow in the higher elevations,” KC said. “That’s when we go ‘OK, we can breathe for a second.’”