In 1850, progress was passing by the town of Fayetteville. In desperation, its merchants made a bold move that didn’t pay off.

Here’s some background:

Robert Fulton’s original steamboats were made to travel on deep rivers such as the Hudson and Mississippi. As the years passed, designers built steamboats that could operate in more shallow waters.

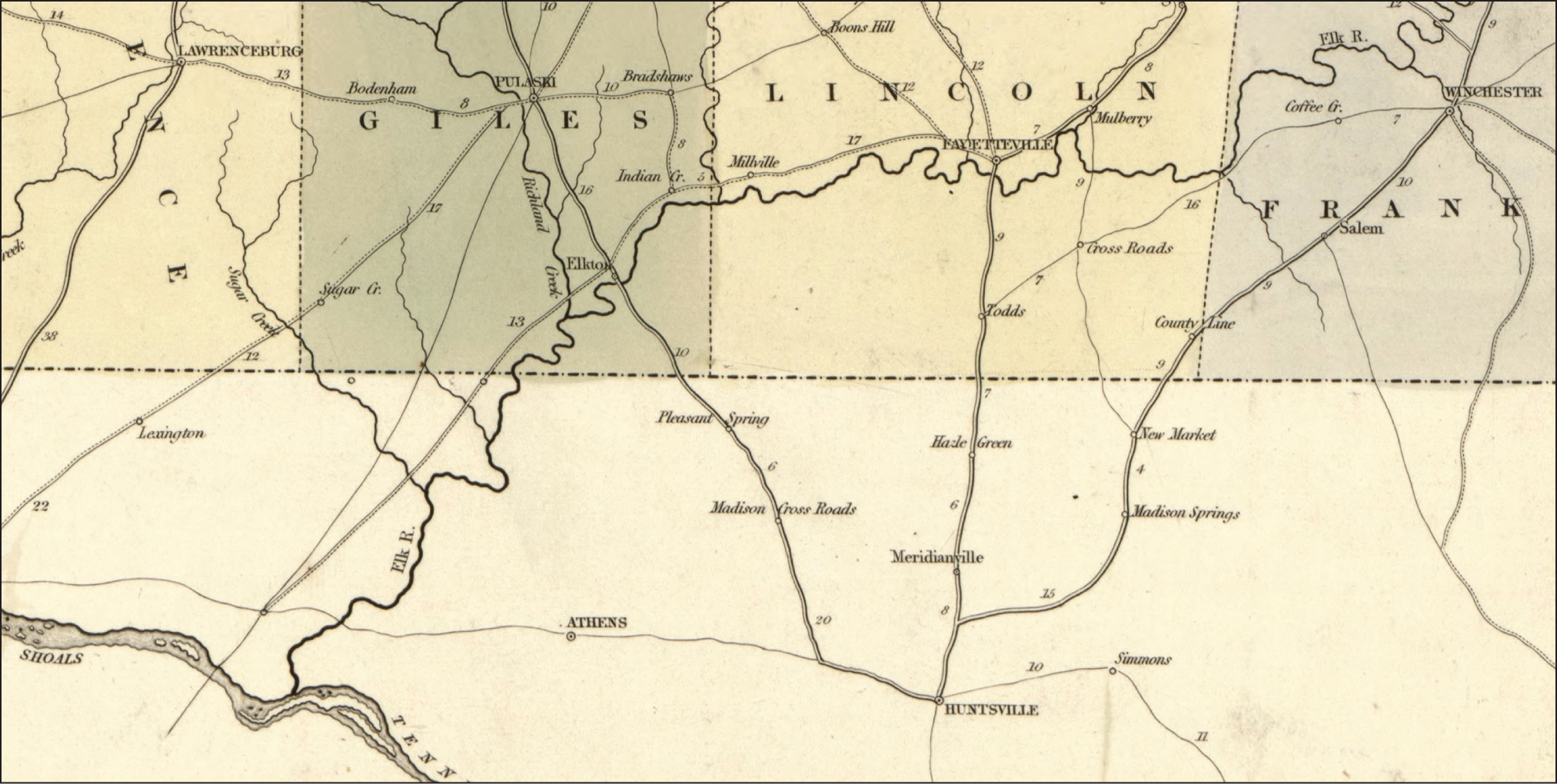

That’s why a steamboat called the Constitution made it to Nashville in 1818 and a steamboat called the Atlas made it to Knoxville 10 years after that. But the Elk River wasn’t as deep or wide as the Cumberland and Tennessee, so no steamboats tried to make it to Fayetteville for many years.

By 1840, Fayetteville was hoping for an eventual railroad connection. But even that development in transportation seemed to be passing the town by. Tennessee’s first railroads to operate near Lincoln County were the one from Nashville to Chattanooga and the one from Memphis to Charleston. The closest Nashville & Chattanooga depot was being built in Winchester (30 miles east of Fayetteville); the closest Memphis & Charleston depot was being built in Decatur, Alabama (60 miles to the south).

Then, in July 1847, a steamer called the Sam Martin left Decatur and made it all the way up the Elk River to the Giles County town of Elkton (25 miles downstream from Fayetteville). The boat was 121 feet long, 18 feet wide and drew only 16 inches of water (it wasn’t carrying cargo at the time). The captain of the Sam Martin was the hero of the day. He predicted that, “with a little improvement,” the Elk River could be navigable seven months of the year.

At the time, each Tennessee county received an Internal Improvement Fund from the state that was typically spent on roads and ferries. From the moment the Sam Martin arrived in Elkton, Fayetteville newspapers began crusading for Lincoln County’s share of that money to be spent on “improving” the Elk River.

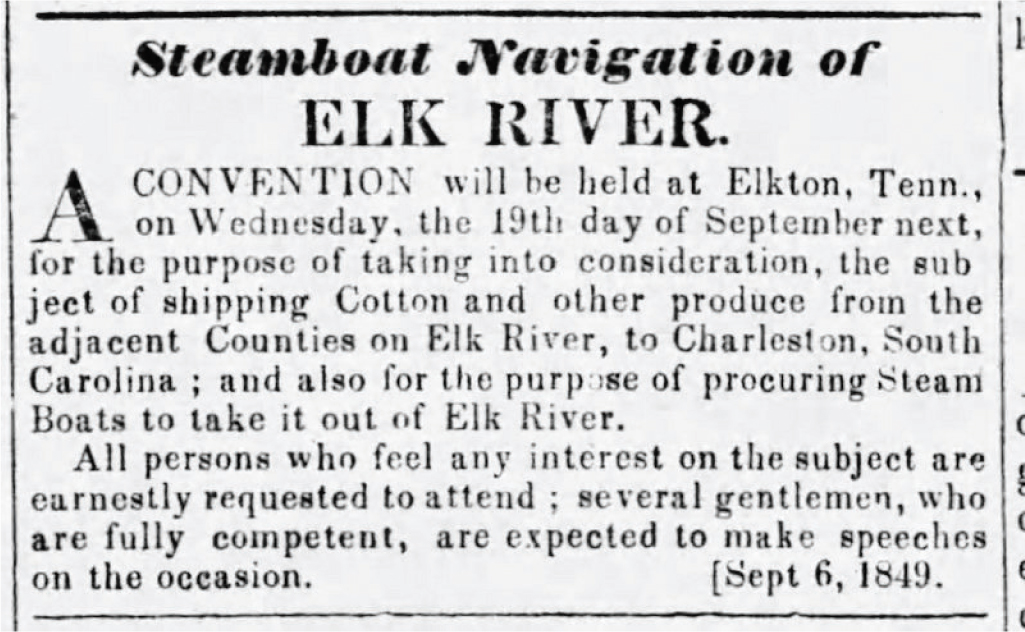

In September 1849 there was a public meeting in Elkton on the subject of steamboat traffic on the Elk River. A few months later, newspapers became boosterish after a second steamboat called the News, then a third steamboat called the George Nicholson, made it to Elkton. “The most incredulous ought, by this time, to be convinced of the practicability of navigating Elk River by steam,” the Pulaski Western Star said in January 1850.

On April 26, 1850, the steamer Union made it all the way to Fayetteville. It was 125 feet long, had 20 state rooms and drew 2.5 feet of water. “At about 2 o’clock, the Union arrived … amid the huzzas and shouts of ‘welcome’ from hundreds of voices on the bank,” the Western Star reported. “Remaining two hours, crowded all the time with visitors, of all ages, sexes and conditions, Captain Spiller kindly consented to gratify the company with a pleasure excursion up the river.”

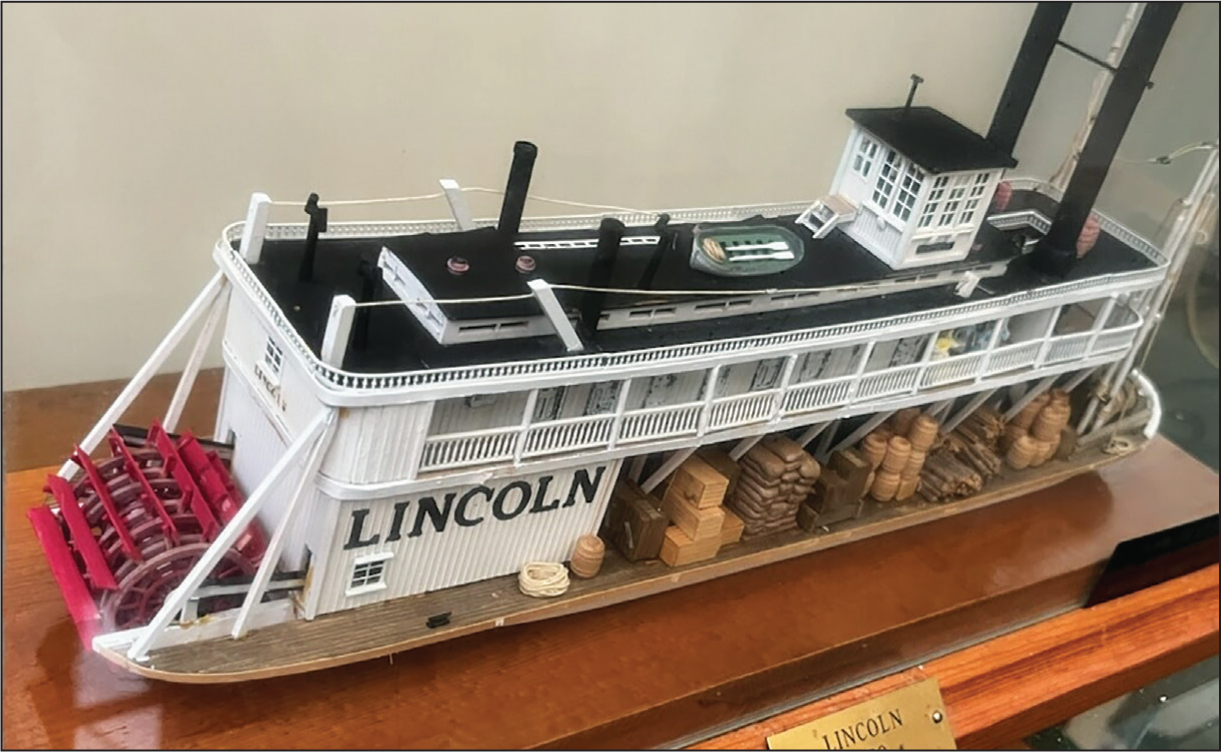

Steamboat fever took over Fayetteville. The Elk River “is soon to become a great thoroughfare of commerce, bearing upon its bosom the products of a fertile soil and an energized industry,” the Western Star proclaimed. Within a matter of days after the Union’s visit, 60 Lincoln County merchants invested $100 each and sent a representative to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to have a new steamboat built from scratch. To honor their home county, the merchants decided to call the boat Lincoln.

(I’d like to point out that it is a coincidence that the first steamboat that came to Fayetteville was called the Union and the one citizens ordered was called the Lincoln. Neither name had anything to do with Civil War sentiments. Lincoln County was named for Benjamin Lincoln of Revolutionary War fame; in 1850, almost no Tennessee residents had ever heard of Abraham Lincoln. Furthermore, the use of the word “union” in 1850 was not a statement of anti-Southern sentiment.)

The steamboat Lincoln left Pittsburgh on Nov. 10, 1850. It traded on the Tennessee River for a couple of months. Then, on Tuesday, Feb. 18, 1851, the Lincoln made it to Fayetteville. “The captain says she can safely carry five hundred bales of cotton downstream and four hundred up, and at the same time conveniently and comfortably accommodate a number of passengers,” reported the Fayetteville Observer.

It was the most optimistic moment in Lincoln County history and was immediately followed by one of the most tragic. On Feb. 24, 1851, a tornado annihilated Fayetteville and left the town in ruins, destroying a Presbyterian church, several stores and about a dozen homes. “The wind roared and blew with fearful violence, a perfect hurricane, amidst which could be heard the shrieks of women and the screams of children, falling houses, crumbling walls, timbers dashing against timbers,” reported the Daily Nashville Union.

The Lincoln had a brief and unprofitable existence. A display at the Lincoln County Museum today maintains that its smokestacks were, at least on one occasion, knocked off by tree limbs hanging over the Elk River. And in early May 1851, the Lincoln hit a boulder in the dangerous part of the Tennessee River known as the Suck, just downstream from Chattanooga, and sank in shallow water.

The Lincoln was raised, but Fayetteville history maintains that the steamboat didn’t make money for two reasons: one, the questionable navigability of the Elk and Tennessee rivers, and two, the eventual construction of the Winchester & Alabama Railroad — a branch line of the Nashville & Chattanooga connecting Fayetteville to the outside world.

Lincoln County invested heavily in the Winchester & Alabama Railroad. The first locomotive rolled into Fayetteville on Friday, Aug. 19, 1859 — by which time, it was probably a bad idea to mention the steamboat Lincoln or the word “union” at a respectable Fayetteville social event.

Note: This column is dedicated to Lincoln County native Adm. Frank Kelso (1933-2013), who was chief of naval operations when I was a lowly lieutenant.