Professional wrestling has often been a family business. In Texas, the sport’s history is synonymous with clans like the Funks, the Von Erichs, and the Guerreros. But few surnames in wrestling history come with a legacy as Texas-sized as Rhodes. To fans across the globe, Austin native Dusty Rhodes was the American Dream, the blue-collar son of a plumber with the slickest tongue in the state, if not the entire wrestling world. Behind the scenes, he wielded tremendous influence as a booker and promoter, responsible for planning the narrative and competitive arcs other wrestlers would perform throughout their careers. In that role, Rhodes was regarded for his creativity, constantly scheming up new stipulations to spice up matches and new ways to tell stories in the ring.

Rhodes died in 2015, but his name lives on in a very real way—not just through the myriad of wrestlers he trained and coached, but also through his sons, Dustin and Cody, who’ve carved their own impressive paths through the sport. In 2019, when Cody Rhodes cofounded the upstart promotion All Elite Wrestling, Dustin was right by his side; the company’s first pay-per-view event was headlined by the brother versus brother bout the two had always dreamed of, which doubled as a tribute to their father in perhaps the only family business where a father would beam with pride over the sight of his boys smeared with blood and tears.

Though Cody has since returned to WWE, Dustin is still hard at work in AEW, bleeding buckets with the best of them, at an age when many wrestlers might be ready to retire. But the 55-year-old Dustin is arguably tougher than ever, writing another page in his storied family legacy every time he steps into the ring. “The passion has come back to me since AEW,” he told Texas Monthly. “It went a little thin towards the end in WWE, and I lost my way because I wasn’t being utilized. I did everything I could possibly think of and had worked with just about everybody. But coming here really opened my eyes. Since day one, it’s been an awesome experience, and we’re just continually growing and trying to get better.”

To casual fans, Dustin might be more recognizable not as himself, but as Goldust, a gender-bending WWE character introduced in the mid-nineties who seemed to have been engineered in a lab to bait headlines and anti-gay reactions. If there was a way to get a rise out of the crowd, Dustin was game for it, whether touching himself sensually in the ring, dressing like Marilyn Manson, or even rocking bondage gear during his matches. As the WWE moved away from shock-and-awe and back toward its family-friendly cartoon roots, Goldust’s transgressive edges got sanded down, but the alter ego still rarely gave Dustin the chance to be himself. Even when he formed a WWE tag team with Cody in the 2010s, the two weren’t billed as the Rhodes Brothers. They were Goldust and his long-lost sibling Stardust, with both their faces hidden under paint.

While the character might not have been his creation, Dustin credits Goldust with forcing him to take risks and think on his feet. “Not every night is going to be one of those top-notch magical nights where the stars align and everything goes perfect,” he said. “But you can have many of those moments over your career if you just continue your growth, continue studying, and not be scared to step outside of your comfort zone. That’s another big thing that I’ve learned since Goldust. I was terrified to do that character, and it felt way out of my league. But it’s when I was scared that the magic happened. Just take a chance. You might surprise yourself.”

With AEW, Dustin’s career has come full circle, not just in its return to an old-school wrestling style, but with an opportunity to represent the Rhodes name. Prior to the sensationalism of Goldust, Dustin wrestled as himself in the WWF (now WWE) and WCW promotions. His persona was all-American and raised right, proudly bearing the surname his father made famous. (His legal name is Dustin Runnels, but to wrestling fans, the Rhodes legacy is more real than any paperwork.) Although it was an honor to carry on the family tradition in the ring, Dustin struggled under his dad’s sizable shadow in the early nineties, and becoming Goldust felt in many ways like an escape from outsized expectations.

“At the beginning, I wanted to be just like my father because he was a god to me,” he said. “I wanted everything he had. Getting into the business as the son of somebody who is such a polarizing figure, people sometimes think [the opportunity] was handed to me, and it wasn’t. Those first couple years, he sent me to Florida and I made twenty dollars a night for two years—just paying my dues, working in front of a dozen people. It took me about six years in the business to figure out that I couldn’t fill my father’s shoes. It’s impossible. But what I can do is take my new pair of shoes, and create something from what my dad created.”

In addition to his father being an inspiration for his sense of creativity, Dustin grew up at the feet of Texas wrestling legends such as “Captain Redneck” Dick Murdoch and the late legend Terry Funk. “I knew Terry my whole life and I learned a lot of lessons from working with him,” Dustin said. “The first time I worked with him, we didn’t say much because he would just react. He taught me that sometimes it’s okay to switch off the train track that you’re on and take a different route, and do things that aren’t planned, because it’s organic. Those organic moments that you weren’t even thinking about in the back are what people remember, because they can feel that it’s not planned.”

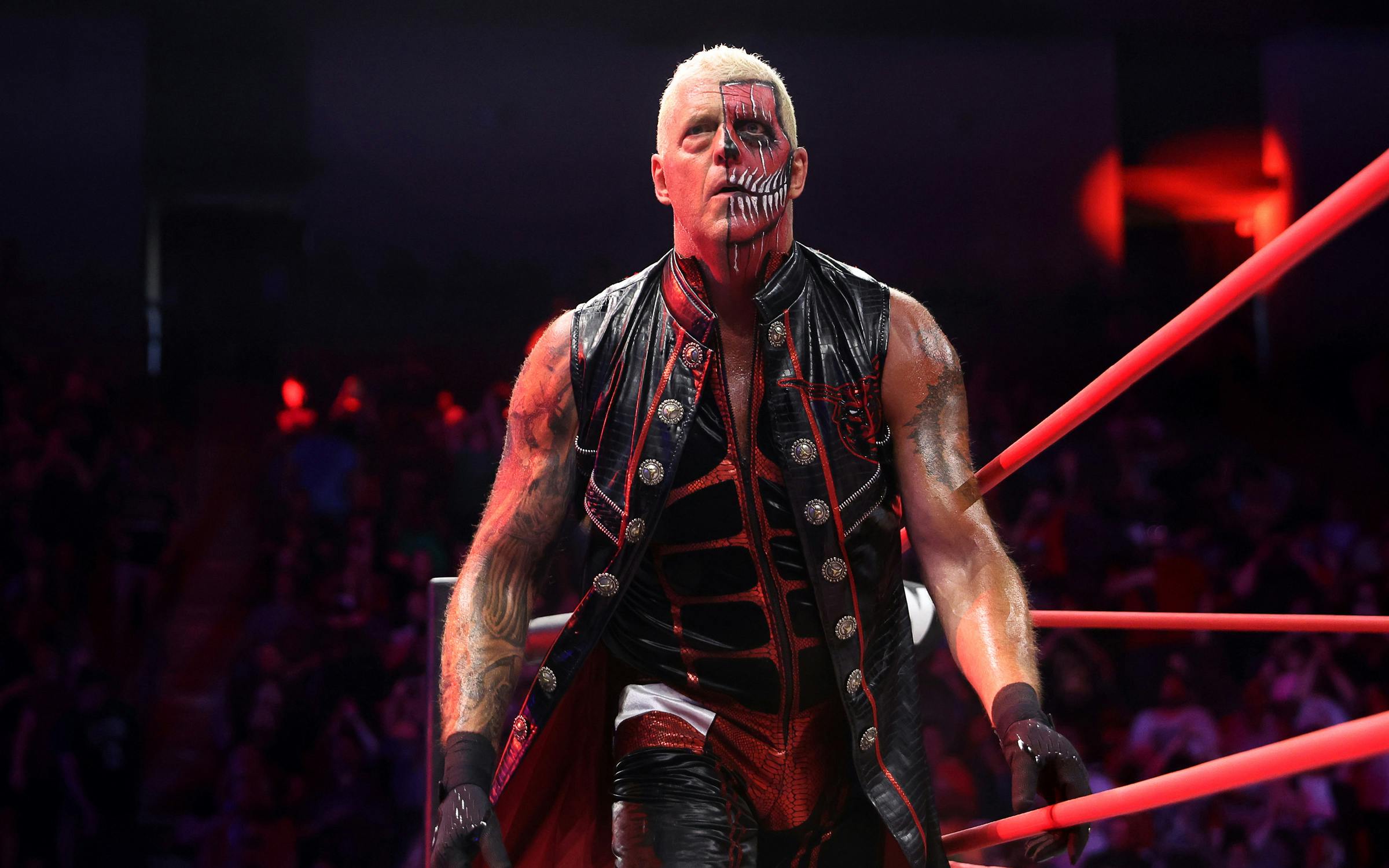

Re-embracing his title as the Natural has been a return to form for Dustin, but he doesn’t shy away from his time in WWE. “I still like to paint my face, which is why I do half,” he said. “So you get Dustin Rhodes, and then you get a little bit of my past.” It’s his way of recognizing both sides of himself—the over-the-top performer who will do anything to entertain a crowd, and the real human being who has overcome tremendous adversity.

Dustin has also helped pass a torch to the next generation of Texan talent. “To me, Texas is really the greatest country,” he said. “Us Southerners love wrestling—especially Texans. Our grannies loved it, and our granddaddies loved it. The wrestling landscape has changed dramatically, but people still want a good story, and I think there’s a place for psychological storytellers like myself who can get the audience intertwined and wrapped up in what I’m doing.”

Recently, Dustin defended the Ring of Honor tag team championship alongside Houston native Sammy Guevara in a deliciously gruesome bunkhouse brawl, a down-and-dirty match variant that Dustin’s dad originated. In a bunkhouse match, wrestlers can use any weapons available to them, from bull ropes to shovels to garbage cans. The competitors often forgo their normal ring costumes for blue jeans and boots before a bunkhouse bout. For one iconic bunkhouse match in 1994, Dustin wore a Texas Longhorns tee with the sleeves cut. “I love the violence,” he confided. “I can just try to explain it like this: When you bleed, it makes things more electric. People see it and they’re shocked, and I want that. I treat everything like a cinematic experience. I call [wrestling] a violent ballet. Some people don’t like to call it a dance, but I do. It’s all about the timing.”

Dustin also currently holds the six-man tag team championship in Ring of Honor—the storied independent promotion now owned by AEW—with Marshall and Ross Von Erich, the sons of fellow Texas wrestling scion Kevin Von Erich. His contributions to the future of wrestling go far beyond Texas, though; Dustin has also played a major role in supporting women’s wrestling at AEW.

“I’ve realized I’m a really good teacher, and I’m proud of myself for that,” he said. “I love when I see these young kids, like in our women’s division, who work with me every single week. Before we’re even supposed to be at the building, they’re training with me. And when I see them go out and do something in a match that I taught them and it works, that’s the greatest payoff. To see them succeeding and getting better is truly amazing. It has nothing to do with money. This is me giving back to the business.”

When he’s not on the road with AEW, Dustin can be found at the Rhodes Wrestling Academy, located right outside of Austin in Leander. “I always wanted a wrestling school, but there was just never time to do it,” he said. “I’ve finally had time to open up and we’re about three years in business right now and pumping out really good students. I teach them a lot of things that other schools don’t teach.” But true to the secretive nature of professional wrestling, Dustin would rather keep those tricks of the trade in the family: “I’m just going to keep those things private because I don’t want anyone else to start teaching them.”

Dustin has teased the possibility of retirement at several points in his AEW career, but he seems unlikely to hang up his boots anytime soon: “I always think I can give a little bit more, because I’m still passionate. Here I am, fifty-five years old, and I’m hanging with the kids and putting on some tremendous matches. I don’t think I’ve had a bad one since I’ve been in AEW, to be honest. It’s shocking to me that I’m still able to do it and that I’ve had a plethora of meaningful matches here in my fifties. Yes, my body is beat up, and I hurt, but I rehab all the time. I’m in the gym every single day, no matter what.”

Pain is ever present in the life of a professional wrestler, and Dustin has endured his share of wear and tear. “Professional wrestlers are some of the toughest individuals in the world,” he said, hitting a reflective note. “We’re a special breed, and by that I mean we’re crazy. Who in their right mind wants to go out and take a bump on the cement? You look at the NFL, basketball, baseball—they all have offseasons, but we’re year-round. We’re constantly going. The train never stops.” In the next breath, he was quick to credit wrestling with keeping him alive—or at least keeping his blood pumping.

“I truly believe that if you sit, you’re gonna die,” he said. “If you keep moving, you’re gonna be okay. It’s a thing I say every day—keep stepping. If I can reach people to just get that in their head, to keep moving forward instead of living in the past, I think that’s a positive thing.”