“I, like everyone else here, believe that … everything possible to liberate Palestine and end the genocide in Gaza must be done,” a senior studying history at the University of Michigan (U-M) told me on April 25, three days after U-M students erected an encampment outside the Hatcher Graduate Library.

The U-M student encampment remained in place from Monday, April 22 until Tuesday, May 21, when officers from U-M’s Division of Public Safety and Security (DPSS) cleared more than 100 tents from the Diag while pepper-spraying students. (DPSS has declined to comment on this article, citing an “open and currently active investigation.”)

The student, who asked to be referred to as “R.” to protect his identity, went on to explain the goal of the Tahrir Coalition, the collective of student groups responsible for organizing the encampment: to convince university officials to divest $6 billion of U-M’s total endowment, which was valued at $17.9 billion as of June 20, 2023, according to a factsheet published by U-M.

Those $6 billion, R. says, are “invested either directly in companies or in managed funds that placed that money further into companies that build weapons of war [and] technology for the apartheid [Israeli state] … that contribute to the genocide in Gaza and the occupation in Palestine at large.”

The Tahrir Coalition has objected specifically to U-M’s investment in companies like Skydio, a manufacturer of military and tactical drones that sent more than 100 drones to Israel as of November 25, 2023; the Israeli spyware firm Oosto; and the Israeli-based surveillance company Attenti, which whom the Michigan Department of Corrections has contracted, among others.

“Making the University of Michigan divest fully those $6 billion from the genocide … would be a huge blow against the apartheid state of Israel and for the liberation of Palestine,” R. said. “That’s why we’re aiming for that.”

The encampment was erected almost five months after the Central Student Government issued two resolutions (13-025 and 13-026) that called on U-M officials to divest. On November 30, U-M leadership canceled votes on those resolutions, and President Santa J. Ono issued a statement indicating that future votes would not be allowed.

“The proposed resolutions have done more to stoke fear, anger and animosity on our campus than they would ever accomplish as recommendations to the university,” Ono claimed. (The office of President Ono has declined to comment on this article.)

In January, the U-M faculty Senate Assembly passed a resolution condemning the university’s “unwarranted interference in the free expression of opinion, and calls on the University’s leadership to protect and encourage the practice of deliberative democracy within the student community.”

(That resolution passed in a vote of 50-5, with two abstentions.)

By Thursday, April 25, the encampment was humming with activity, and one graduate student described the mood as “positive, very hopeful, [and] optimistic.”

Representatives of the Tahrir Coalition estimate the encampment began with approximately 50 campers; by the first night (April 22), they had reached 90, and by April 27, more than 150 students had joined the protest.

“It’s been a little astonishing — the drive to do everything possible,” R. said.

“People are spending their entire [lives] right now working for divestment,” he continued. “The mood has been committed, but there’s a sense of joy and spiritual strength to that commitment, as well. Knowing we’re all in this together, knowing we’re all in solidarity in this struggle, knowing we’re in solidarity with people halfway across the world … there’s joy, there’s commitment, and there’s resolve for divestment from Israel.”

“Palestinians have been oppressed for almost a century now,” said Zainab Hakim, an undergraduate senior studying art history.

“I think it is everybody’s moral imperative to fight for a free Palestine in any way that we can … It is especially, especially our responsibility, as students at University of Michigan, where our endowment is invested in Israel and therefore is also funding the genocide … to make sure that we can stop this.”

“This week, next week, as long as it takes — divestment always; divestment first and foremost,” Hakim said.

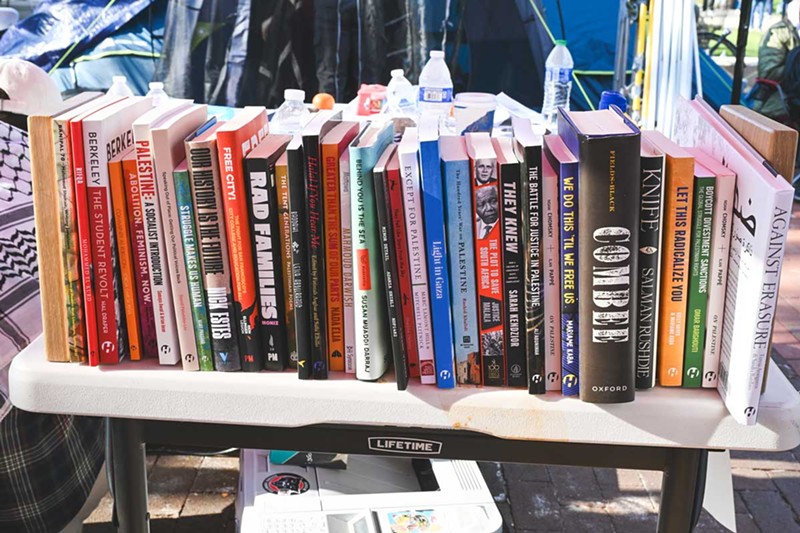

At the encampment, one- and two-person tents surrounded a central hub containing a larger food tent, a station for volunteers, and a small library (the “Liberation Library”), where books, pamphlets, and other forms of media describing the history of Israel and Palestine were made available.

At the food table, donations from local restaurants and other community members were distributed for free, along with bottled water.

“The community has really come together around [the encampment],” Hakim said. “We’re overflowing with donations. We’ve always had more than enough food.”

Doug Coombe

A small library (the “Liberation Library”) at the U-M protest encampment features books, pamphlets, and other forms of media describing the history of Israel and Palestine.

As a whole, the encampment presented a remarkably organized face, with students designated as media or police liaisons and acting accordingly.

Each day, a detailed schedule was posted both on-site and on social media, with teach-ins, workshops on students’ legal rights and de-escalation tactics, yoga and mindfulness sessions, and film screenings.

On the afternoon of April 27, a discussion leader led a group in a reflection exercise: “What is a moment or an experience from the last 200 days that has been difficult for you?” she asked participants.

“I’ve learned so much over the past four days,” said Ekaterina Olson-Shipyatsky, a graduate student in political science.

“Every single day … is packed with teach-ins and art-making sessions and there’s a library where you can read. Even just being in that space and getting to meet people and hear people’s stories about how and why they’ve ended up spending time at the encampment has also been really powerful, profoundly moving, and really educational.”

“Last night the weather was sub-freezing,” R. said, and added that despite the cold, “No one left [the encampment].”

(“I think it got down to 27 [degrees],” another student told me. “I just threw some hand warmers in the sleeping bag [to help] me sleep.”)

“We’re here because we’re committed for the liberation of Palestine,” R. said, “and we will not leave until we do everything we possibly can towards that end.”

Doug Coombe

Many student protesters expressed fear of harm, as well as of professional or academic repercussions.

‘My fear is non-existent in Ono’s and the Regents’ eyes’

“I walk around with my phone in my hand all the time on campus,” a woman who asked to be referred to as “Huriya” told me.

“I walk around with the camera on … ready to press the red button [in case] anybody comes to intimidate me,” Huriya, who was Muslim and wore her hair covered, added. “I should not have to do that on my own campus — I should not feel so unsafe that my camera is there.”

She continued, “But my fear is non-existent in Ono’s and the Regents’ eyes. That’s what’s hurting me.”

Huriya referred to herself as “a very non-traditional student.” She’d begun a degree years before but hadn’t finished; instead, she “waited for my children to be grown” before resuming her studies at U-M.

“I heard it was a very liberal, open-minded university and I thought, ‘This is going to be a place where I feel safe and I feel comfortable,’” Huriya continued.

But after the events of October 7, 2023, “my life was turned upside down,” she said.

Initially, Huriya added, “mentally and emotionally, I was distraught … at what was going on over there — but then I became more distraught at the complacency of our Board of Regents.”

“It is our money [the Regents] use to make those investments, so we should have the right to say where that money goes,” Huriya said, “and we don’t want to kill people — we don’t want people murdered and massacred.”

Everything she’d heard about U-M’s reputation, she said, “was a fallacy — it was all a lie.”

Huriya said her son, a freshman at U-M studying biomedical engineering, had not joined the encampment “because his father does not want him involved.”

“My son is an adult and I feel that he needs to make the decisions,” Huriya added. “What I did tell him was, ‘Make the decision that you can live with.’ … Everyone has to do their own thing that they can live with.”

Zainab Hakim, the senior art history major, made a similar plea.

“What you do now — this is who you are as a person,” she said. “This is your moral course.”

The U-M student encampment was erected days before final exams were scheduled to start, and many students could be seen studying and writing papers on laptops as they sat outdoors.

“I think it goes to show that it’s really hard to concentrate on being a student once you realize how complicit your university is in terrible violence committed by Israel,” Hakim said.

“The bigger thing right now is divestment,” she added. “The fact that so many students are willing to [say], ‘I can sacrifice a grade, I can sacrifice a hangout, or a party, or whatever, for this bigger goal is really important.”

“We’re putting cracks in the ice. Their hearts are full of ice,” Huriya said — though it wasn’t clear whether she was referring to regents, other university officials, or to the Israeli government.

“We’re making change,” she said. “It’s a very slow process, but nothing nurtures overnight. Plants need time to grow. The mighty oak becomes strong the longer it actually stays there. … We might not be able to make the war stop, but we will affect some change whether it’s in somebody’s heart or whether it’s a policy.”

After I had turned off my recorder, Huriya mentioned one more detail: she had a heart condition, she said, and unless she received a transplant in the near future, she wouldn’t live long. She wanted to use the time she had left to fight for justice, for good.

Doug Coombe

Despite widespread claims of antisemitism at student protests across the country, a significant number of Jewish students had joined the U-M encampment.

‘A strong Jewish presence’

“I’ve never felt more at home [than here], surrounded by people who are entirely committed to fighting for justice, even when the narrative is constantly attempting to discredit all of that work,” Alex Sepulveda, a Jewish undergraduate studying political anthropology, told me.

When I asked what he meant when he referred to “the narrative,” Sepulveda said, “We have a black and white fallacy which dominates the way in which we conceptualize Palestine. The vast majority of uninformed people see it as a Jewish-Arab or Jewish-Muslim conflict, when in reality it is a Zionist versus anti-Zionist conflict. That black-and-white narrative is the vehicle by which this university and the United States war machine propels their agenda.”

“Within the Zionist Jewish community, we are often told that there is a place that belongs to us, and us only,” Sepulveda continued.

The Israeli state “operates by manipulating Jewish identity and Jewish grief to enshrine this narrative that Jewish safety is only possible within a Zionist state … but Zionism is inherently racist,” he said.

“When people think of Zionism, they think of a Jewish-majority state, and many of them go about their day as if there’s nothing wrong with that notion,” Sepulveda said. “But we need to understand what a Jewish-majority state means. A Jewish-majority state expressly implies Jewish supremacy. It means that … Jews must be entitled to something that others are not.”

Meanwhile, he added, “the Palestinian narrative is wholly excluded from public education and the American political discourse.”

Despite widespread claims of antisemitism at student encampments across the country, I found that a significant number of Jewish students had joined the U-M protest.

“We have more Jewish people on this side right now than on that side,” Huriya told me.

“Look at that sign,” she added, indicating a table in the food tent. “It says ‘Kosher.’ We’re trying to take care of our … Jewish brothers and sisters.”

“Nobody wants to kill anybody or murder anybody,” Huriya added. “We just want to have a right to exist, too.”

And while I was assured by several counter-protesters who declined to provide their names that it is possible to be both Jewish and antisemitic, there was no evidence to suggest any incidents of what U-M President Ono referred to in an official statement as “violence or intimidation,” other than by counter-protesters themselves.

“President Santa Ono and the U-M Board of Regents have referred to the ‘Jewish community’ numerous times in public communications. In every instance, they’ve referred to them exclusively as one and the same with the Zionist community,” said Sepulveda.

That conflation of Judaism with Zionism, Sepulveda said, is “not only anti-Semitic, but a deep manifestation of their cowardice — because they are fully aware that anti-Zionist Jewish people have strong and uncompromising participation within the divestment movement. Yet they refuse to acknowledge their momentum because they know that it would shatter their narrative.”

Ekaterina Olson-Shipyatsky, who co-founded the U-M chapter of Jewish Voice for Peace, said she helped found the group specifically to make it clear that “an active, visible, loud Jewish presence that’s fighting for Palestinian liberation” was active on-campus.

Doug Coombe

The U-M student encampment was erected days before final exams were scheduled to start, and many students could be seen studying and writing papers on laptops as they sat outdoors.

“The university has done a lot of suppression of the movement on the grounds that it’s suppressing antisemitism or protecting Jewish students,” Olson-Shipyatsky added. “So our presence has been really important in pointing out the hypocrisy in that [claim] and showing what a strong Jewish presence there is in the coalition.”

Olson-Shipyatsky referred to claims that the encampment itself was inherently antisemitic as “preposterous.”

“The encampment is a call for the university to end its complicity in genocide. Ending genocide and fighting genocide and fascism wherever they are is the most Jewish thing I can think of,” she said.

“I think every Jewish person should feel called to oppose genocide with the loudest voice that they possibly can. I think every Jewish person should be fighting to get their university or whatever body they’re a part of to wholly disinvest and oppose the genocide.”

She continued, “We have a lot of banners that say ‘Jews Against Apartheid’ or ‘Jews Demand Divestment,’ things like that. We try to hold those up … to make really, really clear to the Zionists that their claims of antisemitism don’t make any sense.”

She added, “I feel called to be here because of my ancestors. I feel called to be here because of the rich tradition of anti-Zionist Jewish organizing … Jews have been fighting Zionism ever since Zionism existed.”

Alex Sepulveda said that “the conflation of Zionism and antisemitism is inherently antisemitic. The notion that Jewish people are a monolith and that all of them support an ethno-nationalist state,” he added, “is a degradation to Jewish culture.”

Asked about tensions between protesters and counter-protesters, who maintained a small presence outside the encampment, many of them holding or wearing Israeli flags, Olson-Shipyatsky said that (as of April 25) she hadn’t “seen any physical violence or physical altercations” between protesters and counter-protesters.

But, she added, “I’ve heard a lot of really, really nasty stuff from Zionists … really heinous stuff.”

Olson-Shipyatsky described a man who, the previous day, had come into the encampment and “was calling us all Nazis, including those of us who are Jews. He told someone that they would be the first in line for the gas chambers.”

“A woman who was with him [said] another Jewish student [was] ‘not a real Jew,’” she said.

Olson-Shipyatsky believed that both the man and the woman were themselves Jewish, but couldn’t confirm this fact.

In a separate conversation, Alex Sepulveda described other confrontations with counter-protesters.

According to Sepulveda, those confrontations reached a peak at a rally held in support of Israel in the weeks following Oct. 7.

While “hundreds of Zionist parents stood on the [U-M] Diag … dozens of anti-Zionist Jewish students staged a silent counter-protest,” Sepulveda said.

“I’ve been to a lot of protests, I’ve seen people get tear-gassed, I’ve seen people get the shit beaten out of them — I’ve never felt more unsafe in my life than at that protest,” Sepulveda added.

“We endured hours of extreme hate speech,” Sepulveda said, adding that the bulk of the vitriol came from parents of U-M students, and not from students themselves.

“They called us Nazis. They told us that we weren’t real Jews. They threatened us with physical violence and many of them did initiate physical violence against us.”

Sepulveda overheard one parent say, “Your mother’s a whore,” and another say, “You should die in a gas chamber” to anti-Zionist Jewish students.

“None of this is new to us,” said Olson-Shipyatsky.

“Visibly Jewish” protesters at anti-war events “hear this kind of stuff all the time” from counter-protesters, Olson-Shipyatsky went on. “But it’s always — it’s kind of always scary.”

Zainab Hakim, an undergraduate organizer with the Tahrir Coalition, told me, “Our usual rule for Zionists … is that if you can avoid engaging with them, that is always the best course of action. They’re never coming to have a meaningful conversation, they’re never coming to learn — they’re always just coming to harass people.”

On April 27, I approached a small group of counter-protesters to ask if they wanted to comment on claims like these. When I said, “Can I ask you a few questions about why you’re out here today?” an older woman with a Hebrew accent responded, “Why are we here? To support the Jewish students who are passing by and feel, maybe, intimidated.”

“I understand that there are quite a few Jewish students inside the encampment,” I said.

“Why wouldn’t you interview them to see why are they there and not here?” she said.

When I told her that I had, in fact, interviewed students from the encampment, she asked, “What did they say?”

I told her, “I’m really hoping to hear about your opinion.”

“From which newspaper are you?” she asked, and I told her. “What is it?” she said. “Which kind of newspaper?”

Up until now, their group had consisted of two women and two men who appeared to be in their 50s and 60s, as well as a young man who seemed to be a student and stood, silently, with an Israeli flag slung across his back and knotted beneath his chin.

Now, two more young men approached. “Hey, excuse me, guys?” the first one asked, and then mentioned a petition. “We were wondering if we could maybe get a few signatures,” he said.

The woman who had spoken to me asked what their petition was for.

“We’re not totally sure what we’re petitioning for,” the first student said, while the other laughed. “Just, you know, hopefully that these people will leave,” and he indicated the encampment.

The petition, said the second student, “kind of gets the vibe of not being really sure what’s going on. So [we’re] trying to go along with that.”

The woman asked again what the petition was for. “You need to know,” she insisted.

“Just to get these people to leave,” said the first student.

“We’re just a little confused with everything that’s going on,” said the second student.

“You need to write it down,” the woman told them.

“I didn’t really think that through,” said the second student.

“Yeah, we probably should,” said the first.

The woman asked if they were freshmen.

“No, we’re Jewish students,” the first said. “We’re messing with the people at the protest. We’re just, we wanted to—”

Then the woman interrupted them. “You are on tape,” she said, nodding at my phone, which I was using as a recorder. “She tapes you.”

When the first student realized I was a reporter, his tone shifted. He said he found the encampment “a little disruptive, I’m not going to lie.”

The second student said, “I think, personally, everyone has a right to protest in whatever way they want as long as it’s not causing any trouble. I don’t think this is really causing trouble to the point where it should be stopped. I mean, yeah, it’s definitely disruptive, I would say — but it’s allowed within our country—”

“However,” the first student interrupted, “if the protests go to a point where they’re hateful, I do think they should be shut down, and I’m a Jewish student, and I’ll be honest, I haven’t totally felt safe on campus.”

“If you want to go to the graduate library, you have to pass through them,” the woman said, “and the signs … they have there are really uncomfortable — more than uncomfortable — they call for hate.”

I mentioned that multiple students from the encampment had described incidents of harassment by counter-protesters.

“But you see there were no protesters here,” the woman said, gesturing vaguely.

Then one of the students said, “Having gone to protests for things in support of the Jewish students on campus, there have been hateful things said to me and other people around me that have really hurt us, as well. So I would say that’s definitely a double-sided thing.”

Eventually, the woman asked for my name, and when I told her, she lingered over my surname.

“I’m Jewish, too,” I confirmed.

“Being anti-Zionist is antisemitic,” one of the men said. “You can be Jewish and be antisemitic.”

‘A faceless movement’

With one or two exceptions, aside from Jewish students, none of the students I interviewed consented to having their full name or their real name used, out of fear of reprisal or punitive action by university officials or others in the community.

Various students described incidents by “doxers,” or people who attempted to enter the camp and photograph its inhabitants with the express purpose of exposing their identities. To thwart these attempts, many students wore masks and sunglasses.

The doxing “requires us to take a lot of extra safety measures regarding anonymity,” said Hakim, the undergraduate studying art history, as well as “making sure we know who’s in our community.”

This was confirmed by a graduate student who asked to remain anonymous.

“Part of the whole anonymous thing is for safety concerns, because a lot of the students that started camping here are students of color,” he said.

“The other part,” he continued, “is to really enforce the fact that this movement is a faceless movement.”

He then referred to doxing events from the fall of 2023 in which the identities of various protesters had been publicly revealed.

Those incidents had prompted many in the community — both supporters and opponents — to “put some people’s faces … to that movement, and it’s been a struggle to try to separate those faces from the movement.”

He added, “Even if there are key leadership people,” the encampment itself was “about the community — it’s more about a collection of student organizations,” than about any particular individuals.

Ekaterina Olson-Shipyatsky echoed this idea.

“I really want to emphasize that this is a collective project and it’s really only possible by all of us deciding to be here and all of us deciding to put our bodies on the line … for this cause,” she said.

“I think there’s a lot of narrative about there being leaders who are brainwashing the masses, or college students being indoctrinated, and all of this stuff. I see this in the media all the time,” Olson-Shipyatsky added. “I just really want to emphasize that this is a choice that we’re all making. We’ve all been watching a genocide unfold over the last seven months, and this is something that we all feel called to do as a collective.”

When I asked Olson-Shipyatsky if she worried that her involvement with the encampment might endanger her role as a graduate student, she said, “I guess now we’ve seen enough that I know it is a risk. We’ve watched students at Barnard and Columbia get suspended [and] get evicted from student housing.”

She’d witnessed repressive measures at U-M, too, Olson-Shipyatsky said.

“I also have watched, over the last few months, as my peers who are Graduate Student Instructors here face repression for talking about Palestine in the classroom, for talking about Palestine in the workplace. So repression of speech related to Palestine and retaliation for talking about Palestine is not something that’s new at this university and it’s definitely a risk that I’m aware of and that I carry with me.”

Olson-Shipyatsky added, “I would hate for that to happen,” referring to the risk to her position. “I love being a grad student. I really care about my research. I care about my students. I love my program … But I care about ending genocide more.”

Student protesters also endured several violent encounters with the Michigan State Police and the campus police.

Doug Coombe

Police respond to an antiwar demonstration at the University of Michigan Museum of Art on May 3.

On Friday, May 3, the State Police responded with pepper spray and brute force to a demonstration at the University of Michigan Museum of Art (UMMA) after protesters witnessed university Regents Jordan B. Acker, Sarah Hubbard, and Paul W. Brown entering the building.

Nat Leach, a student who was present at that protest, described a scene of “sobbing, screaming, [and] crying,” as police rained pepper spray on students and used batons and even bicycles as objects of blunt force.

Almost three weeks later, U-M’s Division of Public Safety and Security (DPSS) cleared the encampment entirely after protesters staged demonstrations at the private homes of several regents, including Sarah Hubbard.

Citing concerns for the safety of “students, faculty, employees, university visitors, and protesters,” President Ono ordered the encampment shut down by DPSS officers who used pepper spray and batons to enforce the order.

Four protesters were arrested and turned over to the Washtenaw County Sheriff’s Office where, according to one student, they were held in a cell for approximately five hours without the opportunity to wash the pepper spray from their faces.

On June 3, the Southfield-based Goodman Acker law firm, where U-M Regent Jordan B. Acker serves as a senior partner, was vandalized with graffiti slogans reading “U-M KILLS,” “FUCK YOU ACKER,” and “DIVEST NOW.”

While Acker claimed that “singling out a Jewish board member is antisemitism,” the Tahrir Coalition, which stated on social media that an “autonomous group” was responsible for the graffiti, and not the Coalition itself, “applaud[ed] this action as an appropriate response to political entities and individuals’ enthusiastic support of American imperial complicity with the genocide of Palestinians.”

In a statement, the university said, “Freedom of speech is a bedrock principle of the University of Michigan community and essential to our core educational mission as a university,” adding that it “has long welcomed dissent, advocacy, and the expression of the broadest array of ideas, even those that could be unpopular, upsetting or critical of the university.”

It continued, “At the same time, no one is entitled to disrupt the lawful activities or speech of others.”

The university did not comment on how it would handle the protests if they continue into the new school year.

In the days after the encampment’s closure, students chalked outlines onto the bricks outside the Hatcher Graduate Library where tents and tables had once stood.

“We fed each other here,” one chalk drawing read.

“This is where I celebrated Passover,” read a second.

Another chalk slogan read: “Cops beat and pepper sprayed your classmates here / do not walk through here as if things are normal.”