Reuters

ReutersThe rapid spread of mpox – what used to be called monkeypox – in Africa has been declared a global emergency.

A new form of the virus is at the heart of concerns, but there still remain huge unanswered questions.

Is it more contagious? We don’t know. How deadly is it? We don’t have the data. Is this going to be a pandemic?

“We have to avoid the trap of thinking this is going to be Covid all over again and we’re going to have lockdowns – or that this will play out like mpox did in 2022,” says Dr Jake Dunning, an mpox scientist and doctor who has treated mpox patients in the UK.

To assess the threat – despite the uncertainty – we first need to realise this is not one mpox outbreak, but three.

They are all happening at the same time, but affecting different groups of people and behaving differently.

They are labelled by their “clade” – essentially which branch of the mpox virus family tree they come from.

- Clade 1a is causing most of the infections in the west and north of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). This is the outbreak that has been going on for more than a decade. It is spread mostly by eating infected wildlife known as bushmeat. Those who get sick can pass the virus onto people they come into close contact with and children have been particularly affected.

- Clade 1b is the new branch of the mpox family and is causing the outbreaks in the east of the DRC and neighbouring countries. This is being spread along trucking routes with drivers having heterosexual sex with exploited sex workers, with infected people also passing it onto children through close contact.

- Clade 2 is the mpox outbreak that went around the world in 2022 and again had a strong connection with sex, this time predominantly affecting gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men communities (98.6% were men in the UK) as well as their close contacts. This outbreak is not over.

Science Photo Library

Science Photo LibraryTruckers and sex workers

The World Health Organization labelled Clade 1b as one of the main reasons for it declaring a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. This strain has spread to countries previously unaffected by mpox – Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda.

It was first reported this year, but genetic analysis has traced its origins back to September 2023 in the gold-mining city of Kamituga, South Kivu Province, DRC.

“There is a sex industry in the mining city and it has rapidly spread out to border countries because of the massive movement of people,” Leandre Murhula Masirika, a health department research coordinator, tells me from South Kivu.

He said paying for sex was the main way the virus was spreading, but it is then passed from parent-to-child or between children and had been linked to miscarriages.

The outbreak of this new Clade 1b offshoot looks markedly different to Clade 1a.

“It’s really different because the rash is more severe, the disease seems to be going on for longer, but most of all this is really being driven by sexual transmission and person-to-person contact and we haven’t seen any involvement with bushmeat at all,” Prof Trudi Lang, from the University of Oxford, told me on Radio 4’s Inside Health programme.

A key question is why? The answer is either evolution or opportunity.

The new strain does look genetically distinct, but as yet there is no compelling evidence those mutations have made the virus itself more contagious.

Getting into sex workers who have close contact with many other people would also put rocket boosters on an outbreak.

“Transmission through sexual networks occurs more rapidly, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the virus itself is more transmissible,” says Dr Rosamund Lewis, the World Health Organization’s mpox lead.

The virus is not a textbook sexually transmitted infection. However, it is spread through close physical contact and sex obviously involves close contact.

Reuters

ReutersThere is also uncertainty around how deadly the current outbreaks are.

Not all deaths are being recorded as some people are seeking “traditional” rather than hospital medicine. And we have no idea how many people are being infected – some of whom may have mild or no symptoms.

“We just don’t know how many cases there are and for me that is one of the most important unknowns,” says Prof Lang.

History suggests Clade 1 outbreaks are more dangerous than Clade 2. In previous outbreaks up to 10% of people who got sick with Clade 1 mpox died. However, it is not clear how relevant that 10% figure is to the current outbreaks.

And death rates are about more than just the virus. Malnourishment, untreated HIV damaging the immune system or no access to hospital care would all drive up the death rate.

The World Health Organization says 3.6% of known mpox cases died for Clade 1a in 2024. It has no equivalent figure for the new Clade 1b.

Like the early days of HIV

More than 500 people have already died in the mpox outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of Congo this year. The threat posed to the country and its neighbours is clear.

“We have not been able to control the virus in South Kivu,” says Leandre Murhula Masirika.

“We need a massive intervention to control this outbreak and to stop it.”

Prof Lang, who is working with teams in DRC, draws comparisons with the early days of HIV. When I challenge her on this she says it’s a phrase used “not very often and definitely not lightly”.

She says: “That combination of young exploited sex workers, the families, the truckers and obviously the children around all of this who are the vulnerable first victims of this outbreak and this was exactly the same situation in the early days of HIV, where it was really perpetuated by the trucking routes.”

A global threat?

Mpox is not expected to be a Covid-level event. It is already nearly a year since the new strain emerged in September 2023.

The most likely scenario in the UK and similar countries is somebody flies back with the virus and becomes sick.

This has happened multiple times with mpox in the past in the UK and the UK continues to report cases of mpox linked to the 2022 Clade 2 outbreak.

These imported cases could be the end of it or there may be limited spread within households through close physical contact. Sweden had the first Clade 1b case outside of Africa, with no further spread reported.

A more worrying scenario would be a young infected child taking it to nursery or pre-school where they play with other children and cause an outbreak there.

This is the limit of what is being considered likely in the UK.

“No, I don’t think this is going to be a big one,” said Dr Jake Dunning.

“I’m getting a little bit irked and twitchy about people just focusing on what happened in 2022 and thinking that the same will happen.”

Reuters

ReutersThe response would be to find people who came into contact with anyone infectious and vaccinate them, rather than mass immunisation programmes.

It should be easier to stay on top of any imported cases in this way in the UK than in the Democratic Republic of Congo which has added conflict and humanitarian challenges.

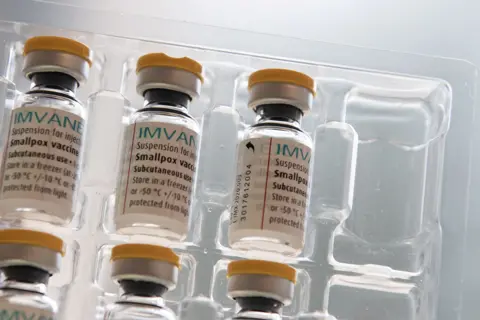

There are still no mpox-specific vaccines but smallpox vaccines work against the disease.

Smallpox and the monkeypox viruses are both Orthopoxviruses and immunity to one leads to protection from the other.

The end of the smallpox immunisation campaigns – after the disease was eradicated in 1979 – is one of the reasons we’re seeing mpox take off now.

Those who did get a smallpox vaccine as children, despite a now aged immune system, should still have some protection.

As will men who were given the vaccine during the 2022 outbreak, although the Clade 1 outbreaks are not disproportionately affecting gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men.

The people with the biggest need for vaccines are the heart of the outbreak in Africa.

Dr Dunning said: “We’re absolutely appalling at sharing tools to prevent mpox, particularly vaccines and that’s indefensible.

“It’s obvious to me that the greatest win for us is controlling these outbreaks at source.”