Why would a self-proclaimed “nervous mom,” whose daughter leaves for college this fall, write a novel that involves a parent’s worst nightmare? “What are you talking about?” Attica Locke recalled telling her therapist, who’d raised a similar question. “That’s just the story.”

The story is Guide Me Home (Mulholland Books, September 3), the final volume in Locke’s acclaimed Highway 59 crime trilogy. Its plot centers on Sera (which sounds a lot like Locke’s daughter’s name, Clara), the only Black member of an otherwise all-white sorority, who goes missing from her East Texas university campus.

The fifty-year-old Houston native admitted that when she writes, “there’s a lot of stuff that’s looking me right in the face that strangely I won’t see until it’s over.” But “over” can be hard to define, particularly in storytelling.

The two previous novels—Bluebird, Bluebird, in 2017, and Heaven, My Home, in 2019—have let readers ride shotgun with Texas Ranger Darren Mathews as he prowls the eastern part of the Lone Star State. On duty and off, the intrepid (yet often intoxicated) Black lawman stumbles through towns that are mired in racism and conspiracies, trying to uphold justice even as he questions his own judgment.

Guide Me Home won’t be the end of the road for Locke’s morally conflicted, emotionally drained protagonist. The author is now adapting her books for television with her sister and writing partner, Tembi Locke. The duo already cocreated From Scratch, a limited series based on Tembi’s best-selling memoir, which chronicled her journey through love and loss following a chance encounter in Italy. It debuted on Netflix in 2022, two years after Locke had begun writing Guide Me Home during the pandemic lockdown.

“I realized if I’m going back and forth,” Locke said of her tandem novel-writing and showrunning duties, “I will be writing this book series until I’m sixty. So I think it needs to close out.”

With the novel finished and the work of writing a show underway, Locke has hit a crossroads with Highway 59, allowing her to look back at where Ranger Mathews has been, where he’s headed, and how her East Texas roots have shaped her narratives.

Highway 59 began as a film script more than two decades ago. After taking her tale of a backwoods murder to Sundance Labs as a fellow there in 1999, Locke landed a movie deal that never panned out. The studio blamed foreign financing challenges, and she blamed “very old narratives that people overseas don’t care about Black life, and they really don’t care about Black rural life.”

The rejection “messed with me,” Locke said. “For a very long time, I just thought, ‘Well, Hollywood doesn’t really care what I think. They don’t really care about the stories that I want to tell.’ ” Disenchanted with the film industry, Locke turned to fiction. She wrote the Houston-set Black Water Rising and its sequel, Pleasantville, as well as the Louisiana-based thriller The Cutting Season. She later found success writing and producing for television (Empire, Little Fires Everywhere). After Bluebird, Bluebird was published, introducing Ranger Mathews, she signed a deal to develop the book for TV. That, too, hit a dead end (though she said it was an amicable decision).

“This has been in my mind and in my soul in some way or another for twenty-plus years,” Locke said of Highway 59. “It gives me kind of a kick to think that we’re here trying it again.”

The “we” is literal. Earlier this year, Attica and Tembi signed a deal with Universal Television that has them developing a still-untitled series based on all three of the Highway 59 books. Asked about collaborating with her sister on a new TV project, Locke summed up the experience in a single word: “joy.”

“What we discovered in doing From Scratch is that we have these complementary skill sets. I hold broad plot really well, and Tembi does interior work really well,” she said. “She will be keeping the heartbeat going, and I’m kind of holding up the structure. And it’s not that either of us can’t do the other one, but those are each of our superpowers.”

The sisters use a shorthand based on decades of shared experiences. At times during a recent writing session, Attica responded with one of two versions of “mm-hmm.” The slow, drawn-out one indicated that she was processing what was said; the quick, enthusiastic version—repeated rapidly three times—meant she was on board with an idea. At the other end of the table, Tembi showed her excitement by bouncing up and down in her seat, breathless and high-pitched as she chimed in to contribute.

At a Pasadena workspace where the Lockes keep separate offices, they took turns playing the big sister. At one point while discussing character development, Tembi (who is older by more than three years) purred, “I’m about to be shady.”

“Go in your corner!” Attica snapped in response.

Later, as their workday wound down, an anxious Attica asked, “Should we work harder?”

Tembi swiftly nipped that in the bud: “Girl, I can’t with you.”

As they fine-tuned their pitch for potential networks and streamers, the sisters revealed that a show based on the Highway 59 trilogy may follow a different chronological order than its source material. “We plan to let the show tell us how the story for television should unfold,” Attica said. The approach allows for what she called “shopping in your own closet,” mixing and matching storylines to fit episodic TV. “If somebody pitches something and it’s really good,” she said of the process, “I feel free because I finished a version of [Ranger Mathews] and there’s going to be this new version.”

One thing that won’t change is the books’ Jim Beam–soaked grit, chased with the verdant landscapes that spread out along a stretch of U.S. 59 as it cuts through the Piney Woods of East Texas, from Houston to Texarkana. In Bluebird, Bluebird, Mathews investigates homicides in the fictional city of Lark, near the Attoyac River in Shelby County; the second book lands him in the wetlands surrounding Caddo Lake. The final tale takes place in Nacogdoches County, from the made-up factory town of Thornhill to the very real Stephen F. Austin State University, where the character Sera is enrolled as an undergrad.

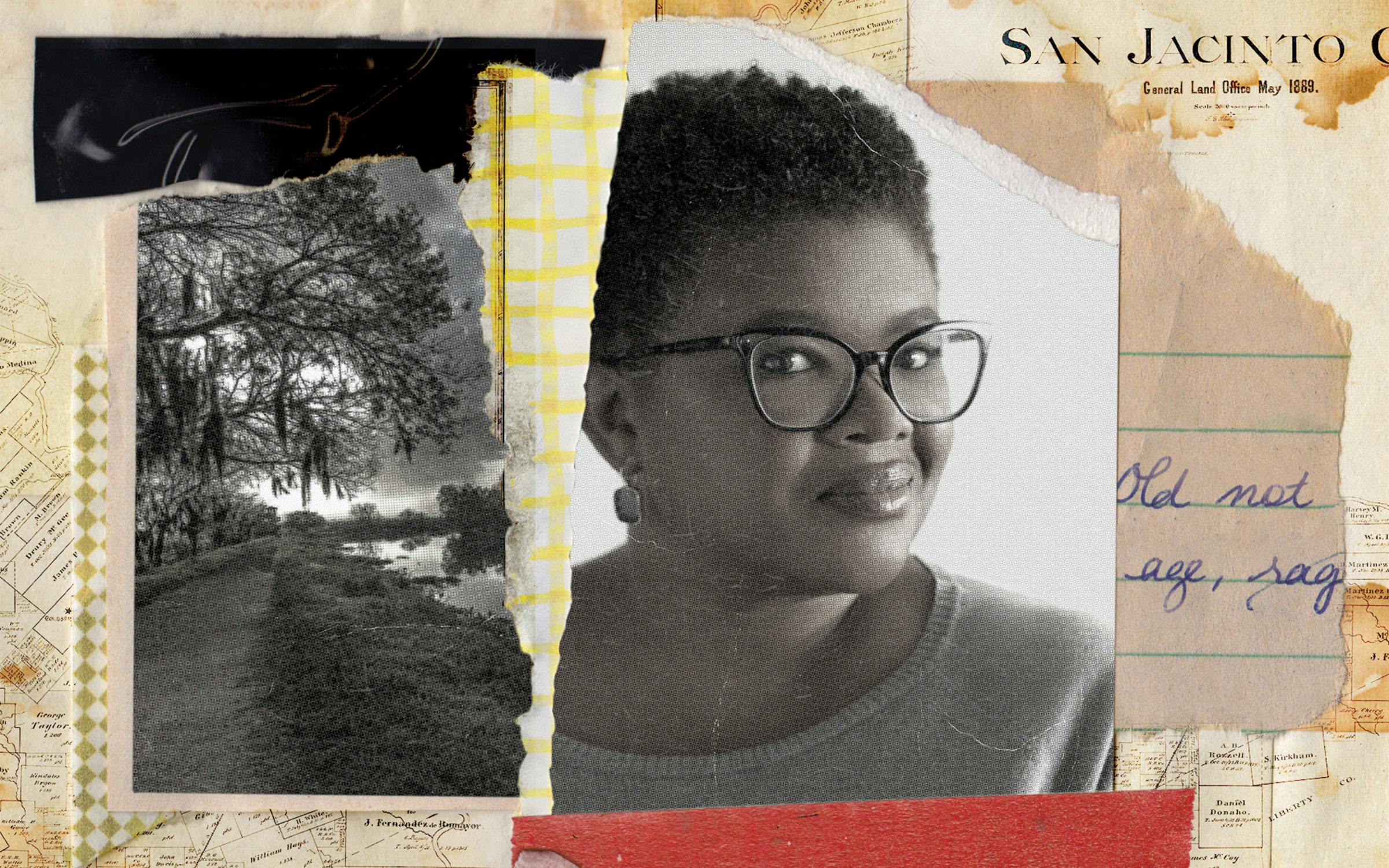

Locke finished her manuscript for Guide Me Home around Christmas 2023 at a home her father maintains in San Jacinto County, about a hundred miles south of Nacogdoches. She described it as a simple ranch-style house, bordered by raw woodland, that sits on approximately a dozen acres that her paternal great-grandfather bought more than a century ago.

“I wrote parts of this book on the land where my grandmother was born,” she said. “When I’m writing Darren’s farmhouse, it’s that space I’m thinking of.”

Seated in a back bedroom of the house that is now her Texas writer’s nook, Locke took inspiration from the rolling hills just outside the window and from the music of Lightnin’ Hopkins. The Centerville-born blues legend is her muse: “He is absolutely, flat-out who I want to be on paper,” she said. “Soulful, kind of sly, kind of funny, sometimes wily, and spare.”

She infused the story with a pastoral feel, recreating the bountiful heirloom-vegetable gardens of local homesteads, the dark green corridors of pine trees, and the red-dirt roads she learned by heart over a lifetime.

Locke finds this terrain and the souls who inhabit it to be fruitful sources of inspiration for depicting a part of Texas she understands and loves deeply. “Maybe why I write about this rural stuff so much,” Locke explained, “is there’s something about being out in the middle of the country with few resources around us, where we’re either going to work together or we’re both f—ed.”

To explain, she recalled listening to conversations between her father and his San Jacinto neighbors—folks who seem to have little in common but take care of each other anyway—about fence repair and feral-hog abatement. “I would be lying if I said I didn’t see a fundamental humanity in agrarian living,” she added.

Locke’s observations of East Texas and its residents are part of what make the Highway 59 series so compelling to read. She engages the senses—the smokiness of red cedar, the thrum of a Chevy truck engine, the glow of a traffic light in a town’s lone intersection—to such effect that even the most metropolis-rooted reader feels they, too, are riding those roads.

With the trilogy completed, Locke hopes she’s offered readers—both outside of Texas and within—an honest view of its complexities.

“My region of the state is worthy of literature, deep thought, and love. East Texas is so not classically beautiful, but so wonderful and raw and evocative and rich and all of these things,” Locke said. “I like that that is written down. If I’ve added to that kind of canon, then I feel very happy and proud.”

Locke has pointed out that her family decided long ago to stay in Texas, despite painful aspects of its history. “My ancestors held strong to a belief that the state’s future would be brighter than its past only if people like us were willing to roll up our sleeves and do the hard work of change,” she wrote in the pages of Texas Monthly in 2012. But that’s not something she chose to do. Instead, she relocated to Los Angeles in 1995 to pursue a career and live as what her father called a “Texan in exile.”

She returns to the state for holidays, celebrations, and reunions with relatives, including a bevy of extended cousins on her mother’s side and three generations of her father’s family. But, Locke adds, “I don’t think I could ever live there again.” She cited what she calls the state government’s anti-transgender, anti-woman, and anti-immigrant policies. “[But] there’s this fantasy that the things that I find distasteful are contained within the borders of my home state, which is not true. I can’t bring myself to hate the state. I will always love what made me.”

Ranger Mathews exemplifies by proxy the mixed feelings that Locke holds about Texas. In due time, those pines she’s rhapsodized about on the page for years will come into full view on screen. And by taking Highway 59 in a different direction, she will invite new audiences to grapple with the culture that still sustains her Texas kinfolk but that she can only revere from a distance.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, a portion of your purchase goes to independent bookstores and Texas Monthly receives a commission. Thank you for supporting our journalism.

Leigh-Ann Jackson is a Washington, D.C. native and former Texas Monthly intern, who now lives in Los Angeles with her husband and their dog.

This article originally appeared in the September 2024 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “An Author Writes Her Way Home.” Subscribe today.