I didn’t have much time. I was in the remote town of Altay in China’s far northwest region of Xinjiang, on the mountainous border with Russia, Mongolia and Kazakhstan, thousands of miles from my base in Beijing as a bureau chief for The New York Times.

In this case, my mission was personal: I was seeking records in Altay’s Civil Affairs Bureau on my father’s service in a Chinese army unit six decades earlier. I knew police officers would soon be trailing me, as they did whenever foreign journalists turned up in Xinjiang.

It was 2014. President Xi Jinping had begun enacting much harsher policies in the region, home to Uyghur and Kazakh Muslims. For centuries, control of the area, a vast land of people from myriad ethnic groups living among mountains, deserts and high steppe has been central to Chinese rulers’ conception of empire.

I knew that finding anything about my father, Yook Kearn Wong, was a long shot. But at the Civil Affairs Bureau, I struck up a conversation in a second-floor office with Wei Yangxuan, a young woman who happened to be an army veteran and helped organize activities for military retirees. I asked her if she knew anything about an old army base of mostly Kazakh cavalry soldiers, where my father and a few other ethnic Han soldiers had served in 1952.

She shook her head no.

I knew I probably wouldn’t return to Altay, and that I had only this one chance. Suddenly I realized it was just past 7 a.m. in suburban Virginia, where my parents had lived for decades. Maybe if I called from my cellphone, Dad could tell Ms. Wei about the Kazakh base.

He answered. I told him I was in Altay.

“You’re where?” he said. He sounded incredulous.

I asked him to describe the Kazakh base to Ms. Wei, then handed her the phone.

They talked for a few minutes. I looked out the window. On the plaza below, I saw two parked police trucks. Around each vehicle stood a few policemen in black uniforms and riot gear — helmets, batons, body armor. I thought I saw one of them look up at the window. I quickly backed away.

Ms. Wei handed the phone back to me.

Dad sounded confused, and a bit concerned. “I just told her about the Fifth Army’s base,” he told me, referring to the unit of Kazakh and Uyghur soldiers in which he had worked. “Now you tell me why you’re in Altay.”

The Uniform

My father rarely talked about China when I was growing up in Alexandria, Va. On nights he came home early, he didn’t sit on the edge of my bed regaling me with stories about his life. In that way, he was like many Asian immigrant fathers of his generation, those men who were intent on building something new for their families and focusing only on what was in front of them.

He had only Sundays off from his job at a Chinese restaurant, Sampan Cafe. On some of those days, we watched American football, and we looked at my math textbooks, algebra or geometry or calculus. He knew numbers. I would learn later that he had studied engineering after the army.

Sometimes I watched him put on a red blazer and black pants to go to work at the restaurant. For decades, this was the only uniform I associated with him.

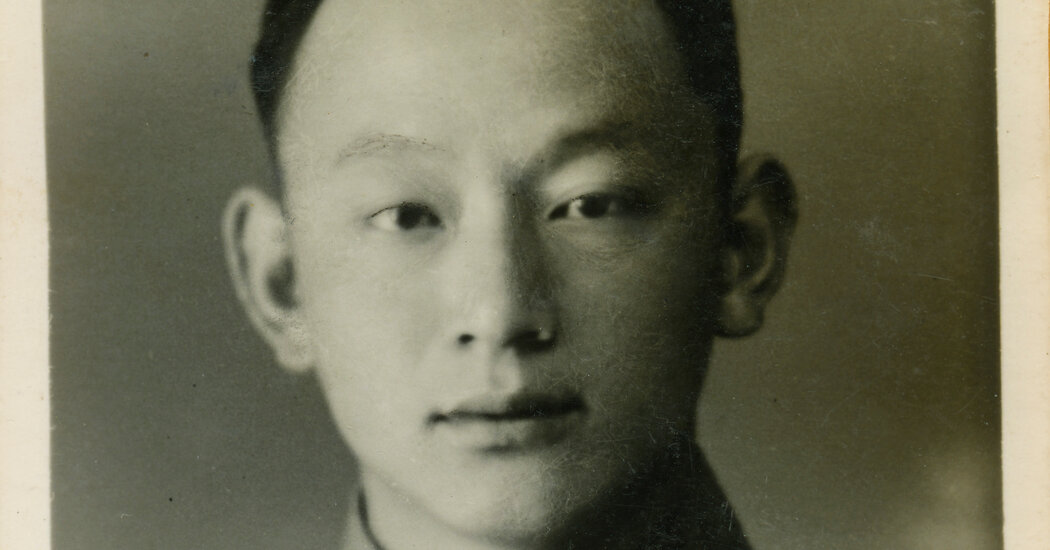

But one day, while I was visiting from graduate school and starting to ask my parents about their upbringings in southern China, Dad showed me a photograph of himself from his days in the Communist army.

It had been taken in northwest China in 1953. My father’s eyes glimmered, and his skin had none of the lines of age. He wore a plain military uniform and a cap. I ran a finger over a darkened spot in the hat’s center. A shadow there. That was where the red star had been, he said. The symbol of the People’s Liberation Army of China. Dad had sent the photo to Hong Kong, where his parents were living at the time, and his father had rubbed out the star, fearful of what the British colonial authorities might do if they saw it.

I learned more about my father’s past after 2008, the start of nearly nine years I spent as a Times correspondent in China. I traveled to Guangdong Province in the far south, where both my father and mother had grown up. That prompted deeper conversations with them and with my father’s older brother, Sam.

My father was born in Hong Kong in 1932 but was forced to move to his family’s home village in Taishan County in southern China after the Japanese army occupied the British colony in 1941. He graduated from high school in the spring of 1950, the first full year of Communist rule, then entered university in Beijing that fall. He had been intent on going to school in the ancient city that Mao Zedong had chosen as a capital because he embraced the Communist cause, believing the new leaders would rejuvenate China after the ruinous policies and corruption of the Nationalists.

There he marched with other university students in a parade in front of Mao in Tiananmen Square. China had entered the Korean War to fight the American military, and he soon dropped out of school to join the new air force. He was proud to do his part to defend the motherland against what party leaders said was an inevitable invasion of China by the American forces once they triumphed on the Korean Peninsula.

His plans were dashed, however, when Chinese officers abruptly ordered him to abandon his training in Manchuria and deploy with the army to the northwest, and ultimately to the frontier with Central Asia. Dad’s offense, he suspected, was that his father was a merchant and had returned to Hong Kong with his mother, while Sam was studying in the United States. Because of that, he was being sent into exile.

It was here that the details of my father’s story remained shrouded in mystery. On that trip to Altay in 2014, I hit a wall: The police officers had indeed found me and followed me until I drove out of town. There were limits to what more I could learn in China.

But when I moved to Washington in 2018 as a diplomatic correspondent for The Times and began working on a book about my family and the arc of modern China, I returned to the subject of Altay and Dad’s other work in Xinjiang. I spent dozens of hours interviewing him in my childhood home, and reading letters he had written to Sam after his military service.

I was fascinated by the details of his role in how Mao and Xi Zhongxun, the father of Mr. Xi, had established military control of the northwest, a crucial moment that few people alive today can speak about. It laid the groundwork for Communist rule over Xinjiang and the quashing of independence movements there, and it presaged more recent efforts by Beijing at repressing Uyghurs and Kazakhs through the internment camp system, forced labor and mass surveillance.

Dad witnessed firsthand the early forms of control that have evolved into what we see today, and was a participant in it. The more I talked to him about his past, the more I realized the value in recording his memories, especially those of his time on the northwest frontier.

Mission to Altay

As my father told it, his trip from Manchuria to the far reaches of Xinjiang took half a year. He rode with other Han soldiers in the open back of army trucks that rumbled along the length of the Great Wall and beyond. He was filled with dread about what awaited him, but he was also struck by the beauty of a China he had never seen.

Heading west from Xi’an, the capital of Shaanxi Province, he remembered the persimmons, plump and smooth and the color of burned copper, hanging low from the trees in the autumn light. How sweet it would be to bite into one. Dust trailed the truck as it continued down the dirt road. He was heading into a vast and sere land, a place of ancient paths and towns, many now long gone. A frontier. The warriors who came before them, also gone.

By the time he reached a sensitive area north of the Tian Shan mountains, near the borders with the Soviet Union and Mongolia, snow covered the ground. In the town of Burqin, Kazakhs rode through the streets on horses. To my father and the other Han soldiers, it was a new world, wilder than any they had imagined existed in China.

He finally arrived at the base outside Altay on Jan. 27, 1952, the Lunar New Year, the start of the year of the Water Dragon. There were 1,000 Kazakh soldiers there. His mission, it turned out, was indoctrination.

Each morning, my father told me, Kazakh soldiers gathered in a hall. The Han Chinese political commissar, who was also the highest-ranking officer, sat at the head of the room, and the other Han soldiers sat near him. He did all the talking. With the help of an interpreter, he ran through the party’s lines of propaganda.

He talked about the Communist revolution and how it was ushering China into a new era. He talked about the end of the old feudal society and the elimination of classes. He talked about the leadership of Mao and the proletarian struggle and the need to resist imperialist powers, especially the United States.

Mao’s revolutionary vision was rooted in an uprising of peasants, like the Kazakh nomads here, and not just in the struggle of workers in cities, the officer said. Though the Han were the dominant ethnic group in the heartland, the officer said the native ethnic groups and the Han had equal stakes in the future of China, and the party respected the cultures, beliefs and autonomy of all the peoples.

The routine was the same every day. In the morning sessions, my father sat quietly and listened to the officer. He thought he couldn’t talk about the party yet with others, to teach its doctrines and its ideas. The party was a mysterious beast, something unknowable for now, and he understood it would take time to learn its ways.

In the afternoons, the visiting Han soldiers huddled in their room, putting their hands near the coal stove to stay warm. It was so cold that the hunks of beef and sheep and horse meat that the soldiers arranged in piles by the wall stayed frozen. Every now and then, outside of the formal sessions, Dad tried speaking with one of the Kazakh soldiers and soon began to learn a few words of their language.

My father told me that relations between the Han and people of other ethnicities in Xinjiang were calm, but I found a darker assessment in a letter he sent to Sam on May 12, 1963, years after he had left Xinjiang. He wrote that the 15 or so ethnic groups he observed had one thing in common, which was “a deep hatred of the Han people.”

Dad described how after 1946, when the Nationalist general Zhang Zhizhong became governor, “the Han were violent and aggressive, actively oppressing the various ethnic peoples, which led the three main regions of northern Xinjiang (north of the Tian Shan) to rise up in revolt.”

As my father began his postings in those volatile northern areas, he hoped the People’s Liberation Army would be able to win the trust of the local groups. Surely Communist governance would be different from the earlier conquests, he thought.

But there were episodes of bloodshed from the start of military rule. In early 1951, a year before my father arrived in Altay, Han soldiers captured a Kazakh insurgent leader, Osman Batur, who had fought for years for nomad autonomy. They executed him by hanging that April. Hundreds of his compatriots fled across the Himalayas into India and eventually ended up in Turkey. Osman became a symbol of Kazakh nationalism.

The Labyrinth

After Altay and a couple of postings in the fertile Ili Valley, my father was sent to the town of Wenquan, near Soviet Kazakhstan, to work on one of the first military farming garrisons set up to control Xinjiang. Senior army officers recommended him for party membership, which filled him with hope.

In 1957, he got the chance to return to interior China and enroll in university in Xi’an to study aerospace engineering. But he soon discovered that he would likely never become a party member. Some officials still harbored suspicions of him because of his family background.

At the same time, Mao threw China into turmoil. During the famine that resulted from Mao’s failed economic policies of the Great Leap Forward, my father had barely enough food on campus to subsist and grew gaunt, with rib bones in sharp relief. His feet became swollen, and he could barely walk. He was one of the lucky ones: Historians later estimated that 30 to 40 million people perished in the famine between 1958 and 1962.

As the famine ebbed, he realized he had to escape China. He managed to flee in 1962 to the Portuguese colony of Macau and then reunite with his parents in Hong Kong. He moved to the Washington area in 1967 with his grandmother to join Sam.

My father managed to avoid the violence of the Cultural Revolution, which Mao ignited in 1966. He told me he likely would have been persecuted by Red Guard zealots, given his family background, and might not have survived. Other family members were not so lucky: A younger cousin who had been a childhood playmate and who was working as a scientist in Shanghai was wrongly accused by Red Guards of being a C.I.A. agent. He killed himself in 1969, leaving behind a wife and two sons.

Decades later, another cousin of his who had grown up in very different circumstances, Gary Locke, would serve in Beijing as the U.S. ambassador to China while I was living and working there.

I marvel at the ways my family’s story has looped like a Möbius strip around multiple generations and around the history of China. Twice, I have stood in Tiananmen Square watching Mr. Xi wave to a military parade, just as my father looked for Mao atop the crimson imperial gate while marching there in 1950.

By moving to Beijing as a Times correspondent, I became a proxy for that immersion in the People’s Republic of China that my father ended in 1962. In a letter to his brother more than four months after returning to Hong Kong, he wrote, “When I think back on these dozen years, it is as if I have gained nothing — a thought that makes me quite melancholic. Normally when I speak to others about this journey, I hide the fact that I was in the army, or that I ever tried to join the party.”

My father turns 92 next month, and he looks back on his years in China now with clear eyes but without that earlier bitterness, having built a life over nearly six decades in America. He even talks about that period with some nostalgia, saying that at least he was part of something larger then, part of a moment when most citizens embraced a sense of national duty and collective purpose.

One afternoon last year, when I was still writing my book, he told me that the Communists had been necessary for China, for reviving it after the war with Japan and the corrupt rule of the Nationalists.

But the party had fundamental flaws. While my father had done everything he could to demonstrate his loyalty, to show he wanted to work for the future of China under the new rulers, even going to the frontier for them, party officials would not bring him into their fold. Mired in their fears, in their ideas of power, in the labyrinth of their own making, they had no reserves of trust or faith or generosity.

Their leaders were no exception, he said.

Years ago, as we sat together in my childhood home after dinner, he told me he still remembered the words to “The East Is Red,” the anthem that most Chinese citizens learned by heart in the 1960s. He cleared his throat and sang the words in Mandarin with no hesitation, even though it had been decades since he had last done this.

The east is red, the sun is rising

From China comes Mao Zedong

He strives for the people’s happiness

Hurrah, he is the people’s great savior!

After he finished, he sat back on the couch and gave me a faint smile. At that moment, he was again the young man in a tan uniform with a red star on his cap riding a horse through the high valleys of the northwest, there at the edge of empire.