Amy Kerkemeyer // Shutterstock

Cities with the fewest community pools per capita

A community pool.

As temperatures rise across the country this summer, Americans will seek out ways to cool off. In the past, many would have flocked to public pools. However, the modern-day shortage of community pools means many don’t have access—in some parts of the country more than others.

Swimply used 2023 data compiled by Trust for Public Land to map the concentration of public swimming pools per capita. Swimming pools only include those managed by public agencies and do not include wading pools or splash pads, which are tracked separately. The data is self-reported by these agencies and is collected across the 100 most populous American cities.

These cities had a median 1.8 public pools per 100,000 residents—little changed from TPL’s 2013 data, the earliest available.

Throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s, community pools became extremely popular and popped up across the northern United States in working-class, white neighborhoods. Thousands of pools were installed throughout the ’20s and ’30s, attracting millions of swimmers each year. The decline in public pools, beginning in the late 1940s in the northern U.S., can be traced directly to desegregation, when white attendance at public pools went into a free fall.

Other cities closed community pools instead of allowing integration. Mississippi alone closed half of its public pools between 1961 and 1972, according to a study published in the journal Southeastern Geographer. Many pools fell into disrepair as funds were spent elsewhere; in other instances, budget cuts prevented necessary repairs or forced closures. Some cities privatized their pools so they weren’t subjected to desegregation rules.

Rather than public amenities, pools became increasingly exclusive to country clubs, homeowners associations, and people’s backyards. The legacy of racism and segregation in pool access has left 64% of Black children without swimming skills, according to the USA Swim Foundation, and many communities without enough publicly available pools.

Swimply

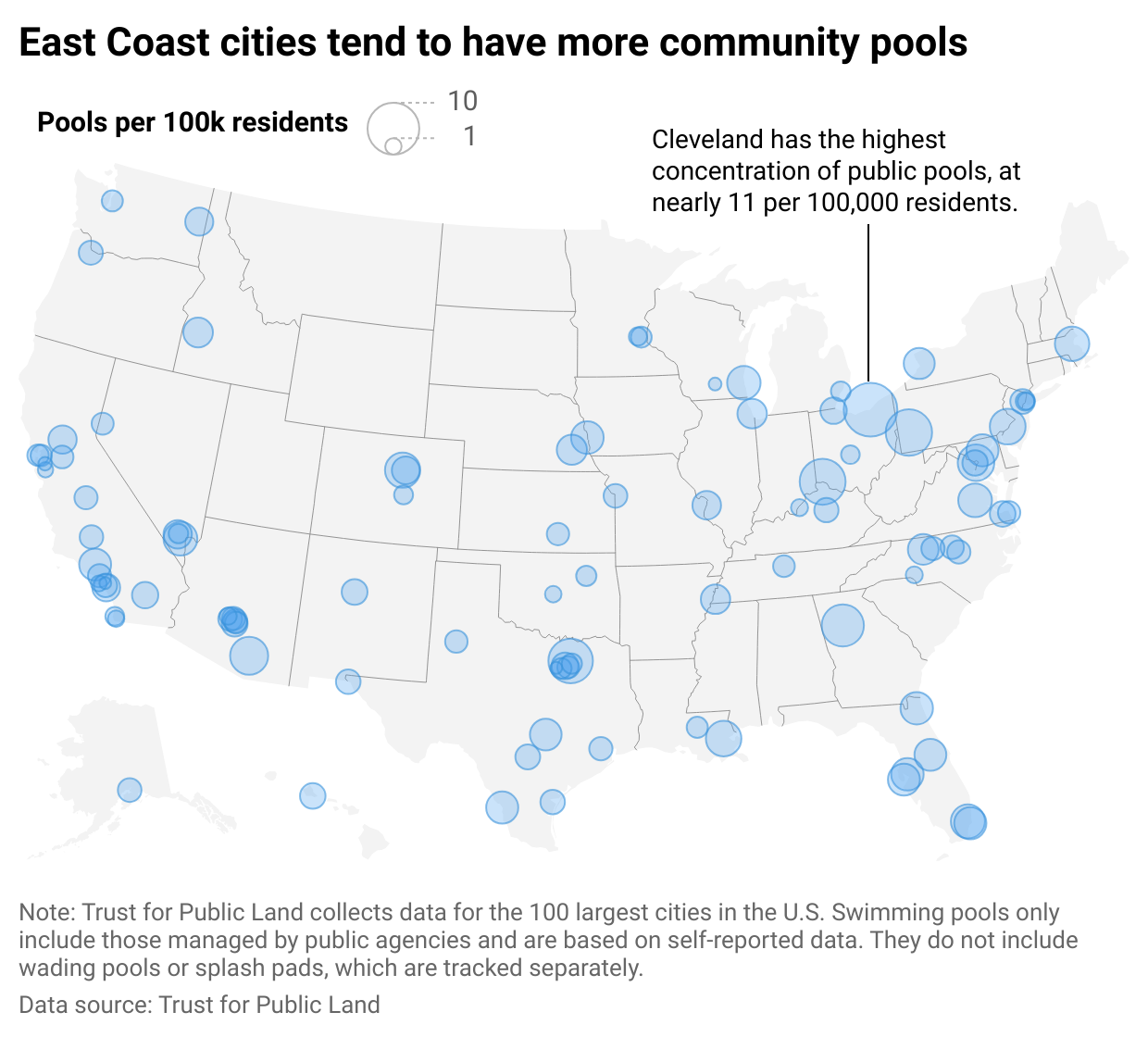

Public pools are more common in eastern US cities

A map of the U.S. showing larger blue circles for cities with higher concentrations of public pools and smaller circles for cities with lower concentrations.

Cities on the eastern half of the U.S. tend to have higher concentrations of public pools. Even the YMCA, a leader in community swim programs, is most prevalent in eastern states, with much lower concentration in the South, in the Mountain Region, and on the West Coast.

Of the 100 cities measured in the public pool data, 13 had fewer than one public pool per 100,000 residents. Anaheim, California, and Forth Worth, Texas, are tied for having the fewest community pools per capita, at just 0.3 pools per 100,000 residents.

In Orange County, where Anaheim is located, fewer than half of the county’s 34 cities have at least one public pool that isn’t located at a school. In 2014, Fort Worth closed five of its seven pools, all of which were located in low-income Black or Hispanic neighborhoods. The city’s 2008 aquatics master plan found the pools slated for closure were losing roughly $30,000 each year, at a cost to the city of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Madison, Wisconsin, and Fremont, California, came in just behind Anaheim and Forth Worth, with 0.4 pools for every 100,000 residents. Cleveland topped the list for having the most public pools per capita, with 10.8 for every 100,000 residents.

With fewer public resources, nonprofits—most notably the YMCA—have provided lower-cost swimming options to people who can’t afford or don’t have access to privatized facilities. Some also access pools through local gyms, though these typically offer exercise-focused forms of swimming rather than the casual dips characteristic of public pools.

Many areas with limited pool access have developed splash pads or spray parks—less expensive water features to provide a place for people to play and cool off. Others have natural water bodies with public beaches and swim areas, which are available for free. For instance, Seattle has three major swimmable lakes, as well as public beaches along the Puget Sound. San Diego, known as California’s Beach City, has few public pools but an abundance of public beaches. Texas has a strong “swimming hole” culture, with natural springs and manufactured lakes spread throughout the state.

These swimming areas create free and natural areas for residents to cool off, but they do come with some added danger. Unlike public pools, many aren’t monitored by lifeguards—even those with murky water, rocks, currents, sudden drop-offs, vegetation, and aquatic wildlife. Still, with added caution and preparation, these water bodies can provide much-needed relief on hot days.

Some cities are taking creative approaches to expand pool access. In 2023, Louisville, Kentucky, provided funding for people to get free summer passes for the YMCA and an amusement park. New York’s SWIMS capital grant program infuses $150 million into safe swimming opportunities for New Yorkers, including $90 million for municipal swimming projects in underserved communities. Among them, the city plans to install a floating pool within one of the city’s rivers or bays.

Public pools have also had to innovate to attract people and ensure their continued operations. Some are adding aquatic play equipment amid necessary renovations, like in Alva, Oklahoma. In Excelsior Springs, Missouri, city officials added an inflatable dome to make the city’s outdoor pool available year-round, and others are using COVID-era federal funds earmarked for outdoor recreation to revive their pool facilities.

Story editing by Nicole Caldwell. Copy editing by Paris Close. Photo selection by Lacy Kerrick.

This story originally appeared on Swimply and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.