In their midyear market reports, commercial real estate firms put a spotlight on concerns about “urban doom loops” in downtowns across the country.

The big worry goes like this: COVID-19 leads to remote work, which leads to companies shedding office space, which pushes office vacancy rates to all-time highs, which leads to loan defaults and reduced property and sales tax revenues, which in turn accelerates disinvestment, crime, homelessness and other ills. People flee, and central business districts become ghost towns.

San Francisco is the deeply depressing Exhibit A of this phenomenon, a formerly vibrant and prosperous real estate market that has been shedding hotels and seeing major retail and office space fall fallow. In a recent commentary, the editorial page editor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch made a similar, compelling case about downtown St. Louis falling into a downward spiral, not least because of pro-gun and other anti-urban policies imposed by Missouri state lawmakers hostile to the city.

As for the Chicago Loop, the jury’s still out.

This summer has brought a welcome increase in tourism, foot traffic and fun activities like Taylor Swift and Beyoncé concerts that make downtown a joy during the warm weather and support the local economy.

But lurking within the city’s impressive skyline is a whole lot of empty office space, owned by landlords who owe more in debt than their properties are worth. With rental income drying up, foreclosures or forced sales could follow.

The big real estate firms estimate that the value of office properties could decline as much as 40% from their pre-pandemic peaks.

Among other market ills, Transwestern cited a massive overhang of unused space that tenants are trying to sublet, which isn’t even counted in official vacancy rates. The Chicago-based real estate firm JLL focused on the split in the downtown office market between hot spots such as Fulton Market and the Old Post Office and pretty much everything else. As JLL put it, there are a few “haves” and a lot of “have-nots.”

As this page has observed on several occasions, downtown needs to be re-imagined as a mixed-use neighborhood, less reliant on office commuters and more welcoming to a diverse array of residents. It needs to be safe and walkable, with green space and the kind of cultural, retail and dining options that make people want to put down roots. It needs housing that’s at least reasonably affordable for everyday families. Remaking this economic engine should be a top priority for anyone who cares about the city.

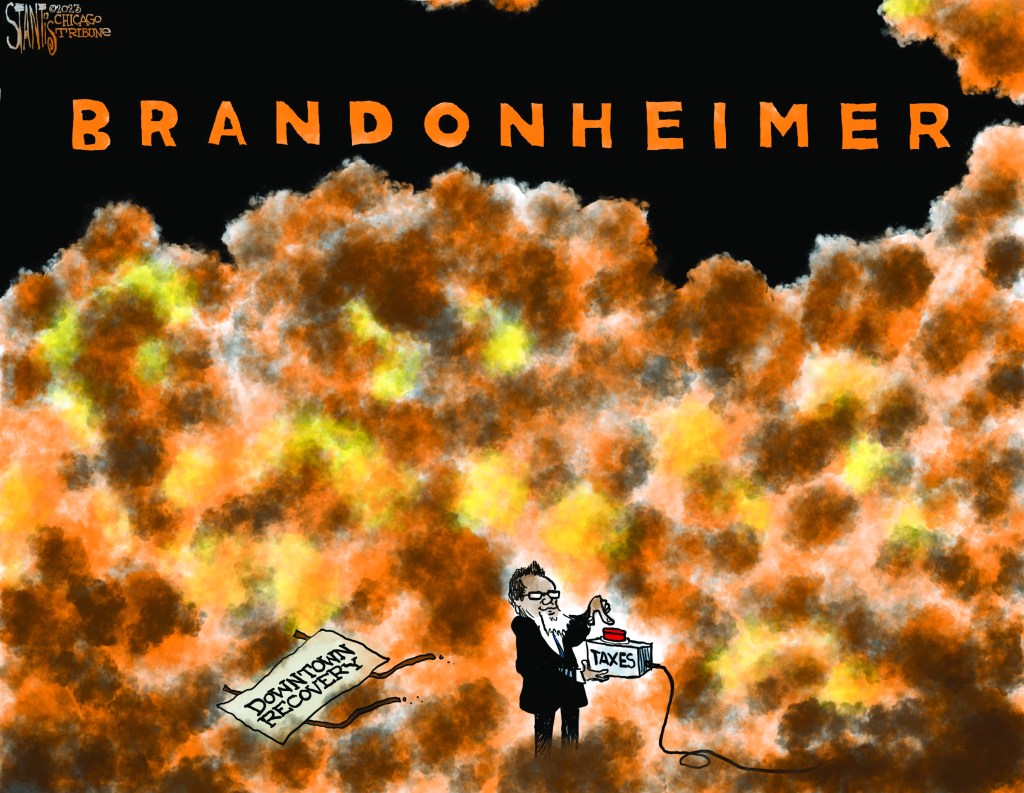

For Mayor Brandon Johnson, who took office in May, a reckoning awaits. Johnson campaigned on raising hundreds of millions of dollars in new revenue to fund projects in neglected parts of the city outside the urban core.

Shortly after he took office, his progressive pals floated a plan titled “First We Get the Money” that fantasized about imposing billions in new taxes, while imagining that those who earned the money would simply hand it over and keep handing it over indefinitely. After the predictable backlash, Johnson retreated from the plan — at least temporarily.

Johnson’s election coincided with a bad time to raise taxes. While the economy overall is pretty good, the outlook is uncertain, and interest rates have shot up. Tax revenues from real estate make up about 20% of Chicago’s revenues, and with valuations of gleaming office towers in major decline, those properties are likely to contribute less. Most of the ideas that Johnson and his fuzzy-math-loving friends have floated would hurt the city more than they would contribute over the long run and make the “urban doom loop” more likely.

Want to run off some of downtown’s top employers? Impose a transaction tax on the financial markets. Want to discourage companies from bringing office workers back downtown? Pass a head tax on each employee, and a tax on suburbanites commuting to the city. Want productive people to leave altogether? Sock them with city wealth and income taxes. Want to chase away visitors? Jack up those already outrageous hotel and entertainment taxes and invent new user fees to make popular events and venues more costly.

Even when Johnson thinks he has a tax idea that could work, he’s wrong. Consider the “mansion tax” he wants to impose on real estate that sells for $1 million or more. As this page has exhaustively explained, what sounds like a soak-the-rich idea that would affect only the upper crust would (as proposed) hammer ordinary folks, hurt small businesses and, crucially, put the city’s real estate market massively out of step with suburbs that charge much less in transfer taxes than Johnson wants.

Ironically, the one tax that Johnson has said he doesn’t want to increase is probably the one where he has the most latitude. Property taxes in Chicago tend to be lower than those in surrounding communities. The city could in theory levy higher taxes by socking it to new property, for instance, or levy for expiring tax increment financing districts, as the Civic Federation noted in a recent research report. It also could simply raise property taxes across the board. It has the legal authority to do so.

Ah, but politically that would be deadly. Chicagoans who supported Johnson understandably want other people to pay more taxes — but certainly not them.

Johnson needs to stop trying to get rich quick by targeting Chicago’s most productive citizens and undertake the arduous work of remaking the city’s core without gimmicks. He needs to partner with real estate owners to sustain the downtown recovery amid the office market crisis. He needs to get busy promoting public safety, workforce development, entrepreneurship and the arts, events and other programs that will keep the heart of the city productive.

Mayor Johnson, downtown matters, and it needs you to be its patron, not a leech.

Join the discussion on Twitter @chitribopinions and on Facebook.

Submit a letter, of no more than 400 words, to the editor here or email [email protected].