Control over state policy in 2025 is likely to come down to just a handful of legislative races this fall.

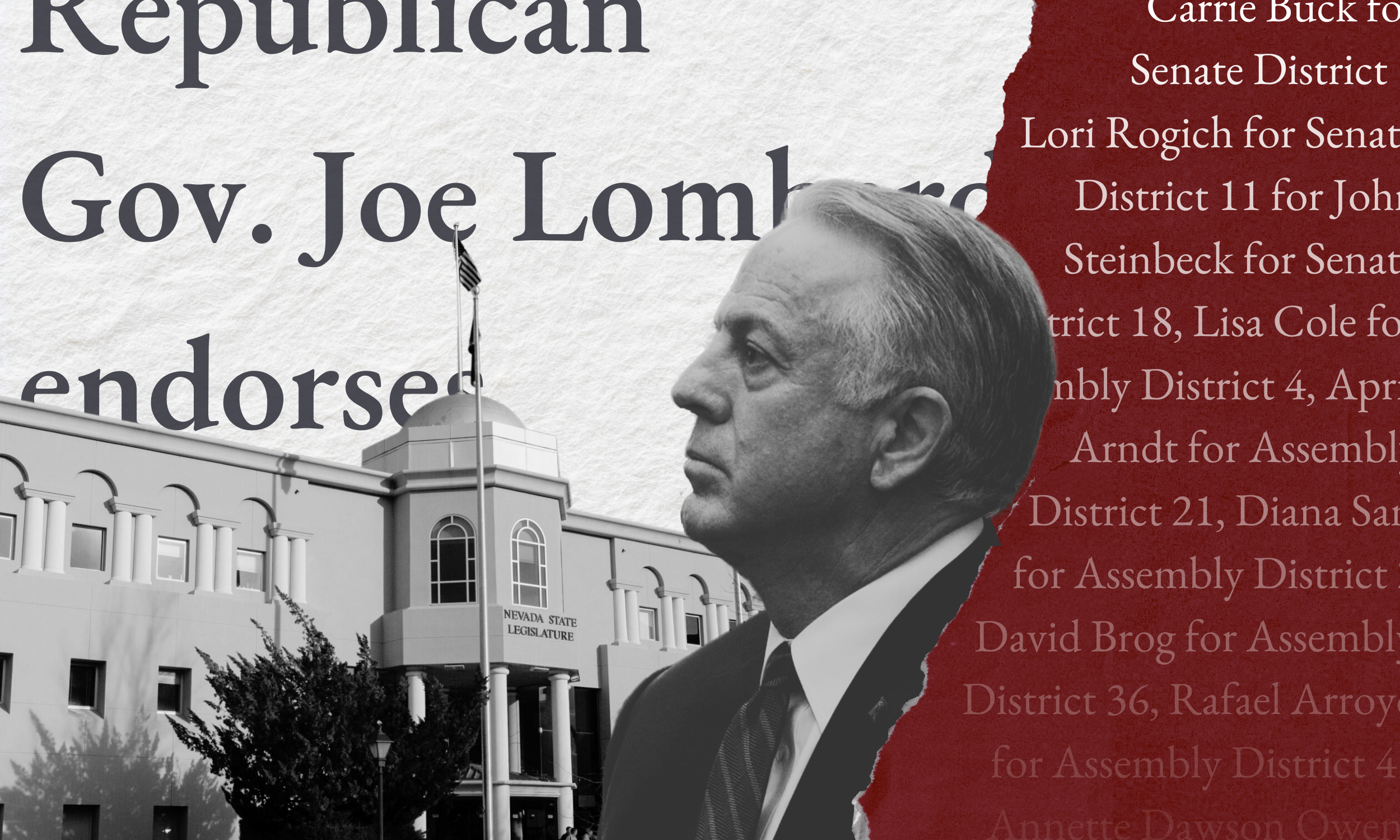

Democrats, who already hold a 28-seat supermajority in the 42-member Assembly, are one seat shy of the 14 seats needed for a two-thirds supermajority in the 21-member state Senate. The party is looking to secure veto-proof supermajorities this election cycle — an outcome that would prove dire for the political relevance of Republican Gov. Joe Lombardo.

For Lombardo, maintaining the power to veto — and with it, leverage over the Democrat-controlled Legislature — rests entirely on Republicans not losing any more ground.

But Republicans have struggled to find consistent success. Outside of the 2014 “red wave” election and subsequent legislative session, Democrats have maintained control of both houses of the Legislature since 2009.

Fueled by the “Reid Machine” built by longtime U.S. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV), Nevada Democrats have pumped out electoral wins in recent years. The party further bolstered its structural advantages in congressional and legislative races in 2021 through control over the redistricting process, which saw Democrats redraw state maps.

Across the aisle, with a state Republican Party hampered by fundraising struggles and legal battles, the responsibility to defend and fight for legislative seats has fallen squarely to Lombardo.

While past governors have waded into legislative races, the potential of being pushed into political irrelevance has led Lombardo to significantly ramp up his involvement in these down-ballot races, including financially supporting candidates in races that may not typically be competitive for Republicans.

A year into his first term, Lombardo’s campaign machinery is taking shape with a trio of well-funded political action committees, a dark money group and Lombardo’s own campaign fund, which pulled in a state-leading haul of nearly $1.5 million in 2023.

Already, Lombardo has endorsed eight non-incumbent legislative candidates running in likely competitive districts, providing a public show of support and financial assistance to their campaigns. In a further connection, these candidates and the pro-Lombardo PACs have paid thousands of dollars to the same subset of Republican consultants who helped the governor win in 2022.

The most public-facing of these groups is Better Nevada PAC — the group that received millions of dollars in 2022 from Lombardo’s top campaign donor, hotel baron and space enthusiast Robert Bigelow — which has unleashed attacks against legislative Democrats as being embroiled in a “culture of corruption.”

Quietly, the Nevada Way PAC — a group named after a unique Lombardo locution — has raised nearly $1 million since late 2022 and directed contributions to his endorsed legislative candidates.

And the Service First Fund, a “dark money” group able to accept unlimited donations without needing to disclose donors, has already run ads targeting Democratic lawmakers in seats Republicans are hoping to flip this year.

While multiple layers of campaign support — including myriad PACs, nonprofits used for fundraising and a state party flush with cash — are nothing new for state Democrats, Nevada Republicans have largely lacked such coordination and cohesion — especially on a legislative level.

As Lombardo’s team revs up its new model, the fate of the governor’s power over state policy hinges on its success.

What’s at stake for Lombardo?

The Nevada Independent spoke with seven political experts with ties to either the Republican or Democratic party about Lombardo’s strategy, granting them anonymity to speak freely about the election and state of the races. They generally agreed on Lombardo’s goals: control of the Legislature, veto power and setting himself up for a successful re-election bid in 2026.

Becoming more involved in the legislative campaigns increases the chances Lombardo will have legislative allies who support his priorities of implementing voter ID laws, more stringent criminal justice policies and school choice expansion.

Republicans believe if Lombardo can successfully pass laws aligned with his agenda in 2025, it will all help him at the ballot box in 2026.

Where those familiar with Nevada’s political playing field differ is in characterizing the governor’s strategy.

Democrats say it’s a strategy similar to the one used by Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin, a Republican who spent $15.1 million through his PAC to engage in state legislative races (and campaigned with Lombardo in 2022).

Democrats note that Youngkin’s model failed when Virginia Democrats defended the state Senate and House by tying Youngkin’s supporters to unpopular policies such as Youngkin’s proposed 15-week abortion ban. Similar to Democrats in Virginia and nationwide, Nevada Democrats have pushed messaging on abortion access this election cycle, including criticizing Lombardo for “cover[ing] up his stance on reproductive rights” and hosting an “extreme anti-abortion group at the Governor’s Mansion.”

Abortion access for up to 24 weeks is protected by state law and can only be overturned by a majority vote of the people.

A person familiar with Lombardo’s campaign efforts downplayed similarities between Lombardo and Youngkin, saying Lombardo’s strategy is not based on any existing model but is intended to level the playing field for legislative Republicans in the Silver State and combat Democratic control of the statehouse and the power of the so-called Reid Machine, which aims to cultivate candidates, train Democratic operatives and turn out the Democratic vote.

Democrats are quick to downplay Lombardo’s efforts as not another Reid Machine. They said that their long-running apparatus aimed at activating a unified ground game established by a U.S. senator unburdened by term limits is very different from one launched primarily to preserve power over the Legislature by a governor who can only serve a maximum of eight years.

However, Lombardo’s endorsements have also extended outside legislative races to include local and congressional candidates, cultivating a slate of Republicans who share his political beliefs. The candidates themselves stand to benefit by association with a popular governor as opposed to the polarizing presumptive GOP nominee.

Jeremy Gelman, an associate professor of political science at UNR, said in an interview that by targeting swing districts, Lombardo’s team is calculating that Republicans less aligned with Trump have better chances.

“They need what is perceived to be a more moderate Republican running in those races, and I think Joe Lombardo knows that,” Gelman said.

One clear example is in Southern Nevada’s Assembly District 2. Incumbent Heidi Kasama (R-Las Vegas) launched a campaign (with Lombardo’s endorsement) for swingy, Democrat-held Congressional District 3 in August, leaving her seat open for another candidate. Clark County GOP Chair Jesse Law announced his bid for Kasama’s open seat shortly before he was indicted for his role in falsely pledging Nevada’s electoral votes to Donald Trump in 2020.

Though Lombardo endorsed Law for Clark County GOP chairman in 2022, Law’s involvement in attempts to overthrow the 2020 election would be a drag on his candidacy and give Democrats a chance to flip the seat. While experts say the district favors Democrats, Kasama — a prolific fundraiser and moderate — won re-election in 2022 by 10 percentage points.

In January, Kasama dropped out of the congressional race to run for re-election to her Assembly seat — in part citing a desire to help Lombardo and legislative Republicans.

“A victory in CD3 would be hollow if the governor was left without his veto ability, and we know how critical that is for our state,” Kasama said at the time.

Where is the money coming from?

Lombardo and the three supportive PACs reported raising roughly $2.5 million in 2023 — a haul headlined by Lombardo’s own $1.5 million fundraising total, which excludes the money raised by his legal defense fund (used to defend a lawsuit related to his gubernatorial primary win and an ongoing ethics case) that is primarily made up of court-ordered reimbursements of legal expenses.

Support for Lombardo came from many of the same donors who powered his gubernatorial campaign, including $20,000 from casinos owned by the Meruelo Group (owner of the Grand Sierra Resort and Sahara Las Vegas). Additional funds flowed in from new donors, including $90,000 from Florida-based alcohol distributor Southern Glazer’s Wine & Spirits, which operates businesses in Nevada, and $50,000 from the Maloof family, prominent business owners involved in sports, gaming and beer.

But no other donor rivaled the Fertitta family, who, combined with contributions from their family-owned casinos, contributed $166,000 to Lombardo last November. Brothers Frank and Lorenzo Fertitta, who sit on the board of Red Rock Resorts and previously co-owned UFC parent company Zuffa, also contributed $500,000 to the Nevada Way PAC just two days before the PAC made contributions to nine Lombardo-endorsed candidates. While state law caps individual donors at contributing no more than $10,000 to a candidate each election cycle, they can give unlimited amounts to PACs.

The pro-Lombardo PACs also collectively brought in $150,000 from The Venetian, the Las Vegas resort previously owned by the Adelsons, a GOP megadonor family.

Pinning down contributions to the Service First Fund — Lombardo’s inaugural committee-turned-dark money group — is more difficult. Because of how nonprofits file and report tax documents, it will be months before the group is required to report information about its 2023 financials, and donors to the group do not have to be publicly reported. A 2022 filing showed that it raised more than $1.3 million and recorded nearly $321,000 in expenses, primarily to “organize inaugural events” for Lombardo. Those figures all came after the group formed in mid-November 2022 and before the end of 2022, and does not reflect any activity from Lombardo’s first year in office.

To capture those missing details, Democratic lawmakers passed a bill on the final day of the 2023 legislative session that would have required state officers to report contributions to their inaugural committees. Lombardo vetoed the bill.

Nevada Democrats have benefitted from similar dark money operations. A dark money nonprofit group called Nevada Alliance gave $2 million to A Stronger NV, a PAC supporting Democratic Gov. Steve Sisolak, in October 2022 just before Sisolak lost his re-election bid against Lombardo. Most recently, the nonprofit gave $500,000 to a group trying to qualify a ballot measure to protect abortion access in the state Constitution.

Where is the money going?

Signs of team Lombardo working in concert can be seen across the campaign finance landscape. Lombardo, the PACs and candidates he endorsed collectively paid more than $291,000 to a trio of top Republican consulting firms last year: November Inc., October Inc. and RedRock Strategies.

Leading the way was November Inc., a Las Vegas-based media and consulting firm led by longtime GOP operative Mike Slanker, that received $140,000 from Lombardo and an extra $6,000 from a combination of Better Nevada PAC and multiple Assembly candidates. October Inc., a firm specializing in fundraising operations headed by Lindsey Slanker (Mike Slanker’s wife), received nearly $79,000 from Lombardo, Nevada Way PAC, Stronger Nevada PAC and a pair of legislative candidates. RedRock Strategies, a firm helmed by Ryan Erwin, Lombardo’s lead strategist from his gubernatorial campaign, received nearly $67,000 from Lombardo, Nevada Way PAC and two legislative candidates.

Lombardo, the three PACs and five of the nine candidates also reported expenses for Florida-based Republican data and advertising firm Majority Strategies, totaling more than $47,000.

Aside from spending on consulting, one pro-Lombardo PAC doled out $30,000 to support Republican candidates in key legislative races. Three Senate candidates received $5,000 each, while six Assembly candidates received $2,500 apiece.

Sen. Carrie Buck (R-Las Vegas) was the only incumbent legislator to receive money from the pro-Lombardo PAC. The remaining candidates include five who are running to unseat incumbent Democrats and three who are running in open seats.

In six of the nine districts where the Nevada Way PAC made contributions, the party registration difference between Democrats and Republicans is within 4 percentage points. The other three races have stronger Democratic leanings, but they are races that both parties consider competitive.

In response to questions about other efforts to support candidates beyond the $2,500 in donations, Better Nevada PAC spokesman John Burke didn’t offer any specifics.

“We fully understand that fundraising is key to success for campaigns. Governor Lombardo’s leadership has been and will continue to be critical to our efforts,” Burke wrote in an email.

How do Lombardo’s efforts compare to past governors?

Nevada governors have for decades engaged in legislative campaign scrums — even in “off years,” when the governor is not up for re-election, according to UNLV history professor Michael Green. Governors are usually committed to their party or their agenda, and “it doesn’t hurt for them to be involved,” he said.

“There’s an old line that [Sen.] Pat McCarran used … ‘When I do someone a favor, I get one ingrate and nine enemies,’” Green said. “But the variation on that is the governor is the one person who can really say ‘no.’ And saying ‘no’ makes enemies.”

Lombardo’s $30,000 to legislative candidates marks a return to Nevada governors pouring resources into legislative races ahead of an election in which they were not running. In 2015, Republican Gov. Brian Sandoval contributed $42,500 to legislative candidates.

In 2019, Sisolak did not pour any money into legislative races — though his inaugural committee directed hundreds of thousands of dollars to a Democratic PAC that supported the state party. A person working closely with the state party at the time said that Sisolak fundraised nearly $1.3 million from 2019 to 2020 as part of a coordinated campaign to help down-ballot candidates.

Midway through Sisolak’s term, lawmakers were running in an election defined by the COVID pandemic, with fundraising hampered amid crippled economic conditions. Ultimately, few seats changed hands in 2020, though Democrats lost their supermajority in the Assembly.

But gubernatorial support isn’t always embraced. Sandoval and Gov. Kenny Guinn — two popular Republican governors who each won second terms in landslide elections (and each by about 46 points) — were scorned by their Republican base after each governor pushed through massive tax increases to help fund education.

After Sandoval secured the passage of the Commerce Tax in 2015 under full Republican control of state government, local parties revolted. The state party denounced him. Republicans who helped Sandoval pass the package were primaried in 2016, even as the governor endorsed and financially supported those who voted for the tax increase and sought to fend off anti-Commerce Tax candidates in the press.

“[Guinn and Sandoval] were anathema to a lot of dedicated Republicans in the next legislative election,” Green said.

But governor and presidential elections don’t happen in the same year, and the two types of election cycles have significantly different electorates, according to UNR’s Gelman. In presidential years, any kind of nuanced messaging about the consequences of a state legislative race — in this case, the potential for a supermajority — “is going to get drowned out amongst 1,000 other talking points.”

“Whether or not voters are paying enough attention to [the Legislature],” Gelman said, “in a cycle where they’re choosing between, potentially, Donald Trump and Joe Biden — it’s a totally different story.”