Dan Chapman is a self-described “mountain man” whose career as a reporter, most recently at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, allowed him to write a lot about climate change, water wars, sprawl, endangered species, pollution, coal ash and more. He was looking for a way to tie these disparate environmental issues together when inspiration struck.

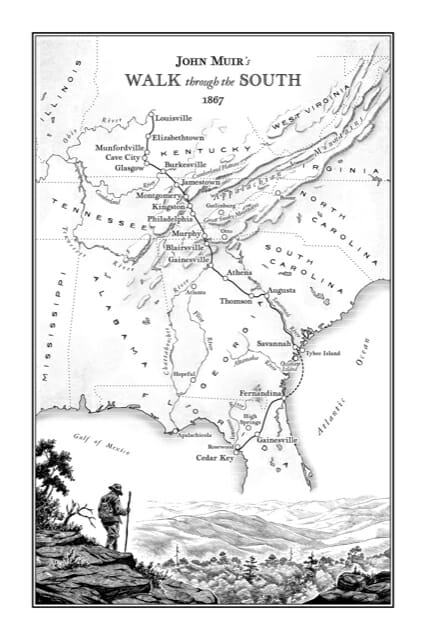

“The light bulb went off when I stumbled upon John Muir’s A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf,” says Chapman, who currently writes stories about conservation in the South for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Muir, literally, gave me a roadmap to follow to highlight the South’s ecological beauty and its environmental woes.”

The result, A Road Running Southward: Following John Muir’s Journey through an Endangered Land (Island Press, 256 pages), chronicles Chapman’s path from Kentucky southward to Florida 150 years after Muir’s expedition along the same path. Part-love letter to the natural world, the travelogue is primarily an environmental cri de coeur about the ecological devastation wrought by global warming and the misuse of dwindling resources.

In advance of his book launch at Manuel’s Tavern on Thursday, Chapman shared his thoughts with ArtsATL on the agony and ecstasy of following in Muir’s footsteps; the baby steps anyone can take to be better stewards of the planet; and his zeal for the South’s biodiversity.

In advance of his book launch at Manuel’s Tavern on Thursday, Chapman shared his thoughts with ArtsATL on the agony and ecstasy of following in Muir’s footsteps; the baby steps anyone can take to be better stewards of the planet; and his zeal for the South’s biodiversity.

ArtsATL: According to one biographer, Muir’s “transformational moment” began with his experience at Bonaventure Cemetery in Savannah. How did his experience in Savannah wind up being foundational to his environmental, ethical and philosophical beliefs? What was your experience of spending a night in the cemetery?

Dan Chapman: For Muir, Bonaventure was life-changing in that a half-dozen days spent amidst the dead gave him a better appreciation of the living, natural world. He decided that all animals, plants, and insects, even “the smallest transmicroscopic creature that dwells beyond our conceitful eyes,” are no less important than homo sapiens. And all will be crushed by man, Muir determined, if efforts weren’t made to protect creatures great and small, as well as their habitats. In short, Muir’s bedrock philosophy of conservation that led to the creation of Yosemite, other national parks, and the Sierra Club was crystallized in Bonaventure.

For me, the cemetery was an honest-to-God attempt to channel Muir, to physically place myself in his boots while thinking “big thoughts” about the environment and man’s never-ending attempts to harm it. By midnight, I was a little depressed (and tipsy) by the damage done to the South’s beauty and biodiversity. In the morning, though, as the marsh magically changed colors with the rising sun and the elegant white herons set about breakfast, my mood brightened considerably. There’s a lot of the natural world to be proud of in the South, I realized. Plus, I didn’t get arrested for trespassing.

ArtsATL: Over the course of your journey, did you ever experience the kind of euphoria or despair Muir described in his journals?

Chapman: Lord, yes. I, too, revel in the cascading Appalachian ridges stretching to the horizon. And the dark beauty of a cypress-oak-and-moss-draped swamp. And the limitless possibility of the Gulf of Mexico “stretching away unbounded, except by the sky.” I, like Muir, groove on the incredible biodiversity of the South’s plants and animals and the hidden-away places where they live.

I can’t say I ever despair as much as Muir. I get depressed about the damage done to a mountain peak, a stream, or an underground aquifer. And I’ve apologized already to my children for the sorry state of the climate perpetrated by my generation and predecessors. But I never dip into the heavy melancholia that Muir experienced, whether induced by malaria, an overbearing father, hunger, or his dogmatic religious upbringing. I’m a pretty optimistic chap. And that carries over to the future of the South’s natural world.

ArtsATL: Who/what inspired your curiosity about/appreciation for the natural world?

Chapman: I spent many summers in Vermont as a lad hiking the Green Mountains and sleeping under the stars. Like Muir, I’m a mountain man. When I moved South, first to North Carolina, then to Georgia, I backpacked the Smokies, Nantahala, Pisgah, Cherokee and Chattahoochee national forests and parks. In my work, I’m fortunate to spend time with ecologists, biologists, climatologists, riverkeepers, farmers, oystermen and nonprofit experts who can explain the natural world while imparting their love of the outdoors.

ArtsATL: Was there a turning point when your casual interest evolved into a sense of personal responsibility for preserving/conserving the planet’s natural resources?

Chapman: As a journalist, you keep a professional and emotional distance from the people and subjects you cover. As a human being, though, you can’t help but get angry at the damage done by the “devotees of ravaging commercialism (who) instead of lifting their eyes to the God of the mountains lift them to the Almighty Dollar,” as Muir so eloquently put it. Five years ago, I was casting about for a way to tell folks about the accumulation of environmental problems that, left unaddressed, would spell disaster for the South. A Road Running Southward gave me the freedom to report a straightforward journalistic piece while hammering home the dangers we face.

ArtsATL: Urban and suburban communities tend to yield entire populations who are desensitized to the life cycles of flora and fauna. What are some small steps well-meaning individuals can take to be more mindful and careful stewards of our planet?

Chapman: Look, nobody sets out to destroy the planet, trample the flora or kill the fauna. Most hunters and fishers love the outdoors and pay beaucoup dollars in excise taxes on hunting and fishing gear that goes for the conservation of lands and waters. Our problems, not surprisingly, revolve around greed, selfishness and ignorance. If there’s money to be made, well, the field of wildflowers gets cemented over. Plantation pine trees grow quicker and pay more than a natural hardwood forest. It’s cheaper to build septic tanks — where sewage seeps into the groundwater — than run a sewer line into the country.

Since everything’s about money in this country, you have to put a value on a mountain vista, bubbling stream or natural spring. We must educate people about the “ecosystem service” benefits — clean air and water, carbon sequestration, hunting, hiking, birding, animal protection, forest bathing, etc. — that fields, forests and nature provide. People can put their farms and fields into conservation easements that preserve the land in perpetuity. They can spend a buck more on coffee or cheeseburgers if that dollar benefits the environment. Buy an electric vehicle. Demand renewable energy. Contribute to an environmental nonprofit. Vote the “temple destroyers,” as Muir called them, and their colleagues, out of office. There are many things we can do to better the planet.

ArtsATL: Having to shelter in place at the start of the pandemic opened a lot of people’s eyes and ears to some of Mother Nature’s simple pleasures — including birdsong, the spectacle of fall foliage, watching tides rise and fall — which they’d previously overlooked. In your experience, has the heightened awareness been sustained? If so, has it led to concrete action in the effort to stem climate change?

Chapman: That’s a great question. I wish I had a great answer. We know that more people took to the mountains and coasts than ever before. Example: the Great Smoky Mountains National Park welcomed a record 14 million visitors last year. Second-home sales in the mountains and along the coasts skyrocketed. And people hungered for greenspace, birdsong and vegetable gardens. But, again, humans are a relatively selfish, short-sighted species. We worry more about Covid-19, inflation, and the Russia-Ukraine war than we do climate change. Large swaths of the world will be uninhabitable by 2100, but, hey, how’s that 401(k) doing? There was a good push by the Biden administration and other nations to tackle climate change two years ago, but events since have relegated concrete action to the back burner. That’s sad. And dangerous.

Chapman: That’s a great question. I wish I had a great answer. We know that more people took to the mountains and coasts than ever before. Example: the Great Smoky Mountains National Park welcomed a record 14 million visitors last year. Second-home sales in the mountains and along the coasts skyrocketed. And people hungered for greenspace, birdsong and vegetable gardens. But, again, humans are a relatively selfish, short-sighted species. We worry more about Covid-19, inflation, and the Russia-Ukraine war than we do climate change. Large swaths of the world will be uninhabitable by 2100, but, hey, how’s that 401(k) doing? There was a good push by the Biden administration and other nations to tackle climate change two years ago, but events since have relegated concrete action to the back burner. That’s sad. And dangerous.

ArtsATL: In the parlance of millennials, John Muir’s record on race was problematic. What was the problem? Did his shortcomings diminish your regard for him as a humanist and environmentalist, or give you pause when deciding whether or not to tell his story?

Chapman: No question Muir was a racist. And I say so in the book. He denigrated Blacks and Indigenous peoples with the usual racist crap common among Whites of his day. It was really disheartening to hear him talk of “Sambo” and “savages.” Muir fans say he was just a product of his time, an out-of-touch Scotsman via Wisconsin who had never really met people of color before so he should be excused his ignorance. And, yes, his views on Native Americans and Native Alaskans became more enlightened as he grew older.

But none of that excuses his hurtful and ignorant words and ways with their not-so-subtle recommendation that the Great Outdoors would be better off without “dirty” people of color. It greatly diminishes Muir as an apostle of preservation and godfather of the modern conservation movement. But it doesn’t make disappear the impact that Muir had over successive generations of (White) conservationists and their creation of the modern conservation movement. His legacy, though tainted, is set. My book is not a biography of John Muir. It’s a travelogue of modern environmental ills with Muir as erstwhile guide, not God. I believe he should be kept in proper perspective.

ArtsATL: What do you want readers to take away after walking in John Muir’s shoes?

Chapman: I want them to see the South of 150 years ago. I want them to compare then to now. I want them to understand the damage we’ve done to this beautiful land before it’s too late. And I want them to get angry and demand change. Change can be as small as pulling a tire from a beautiful creek or voting for the politician who’ll push renewable energy. If you’ve got money, buy an EV, put solar panels on your roof and donate to the wonderful nonprofits that fight to conserve the land and waters. We should be ashamed of the planet we’re leaving our children and grandchildren. Didn’t our mamas tell us to pick up after ourselves?

ArtsATL: How were you changed as a result of researching and writing A Road Running Southward?

Chapman: In reporting for a daily paper, you write about certain places and people in a moment in time. In writing the book, I had a chance to knit all these disparate issues together into a broader-brush mosaic of a region in trouble. It’s the Big Picture of how we got here and where we’re (hopefully) not going. I knew, starting out, about most of the environmental ills bedeviling the South. I knew about the beauty of the mountains, plains, rivers, swamps and coasts. But I was blown away by the biodiversity of the region’s plants and animals. I mean, there’s an absolutely beautiful yellow flower called a “spreading avens” that literally climbs uphill in search of cooler weather. Fascinating. And I discovered a ghostlike shrimp that lives in caves but succumbs to above-ground pollution and climate change. Really, no region’s beauty and biodiversity compares to the South’s. I have a newfound zeal to keep it that way.

::

Gail O’Neill is an ArtsATL editor-at-large. She hosts and coproduces Collective Knowledge a conversational series that’s broadcast on TheA Network, and frequently moderates author talks for the Atlanta History Center.