How do we make sense of the world? Time spent in Davos last week crystallised my answers in the form of twelve propositions.

Proposition one: the world is menaced “by the sword, by famine and by pestilence”, as Ezekiel warned: first Covid, then war on Ukraine and then famine, as exports of food, fertilisers and energy have been disrupted. These remind us of our vulnerability to unpredictable — alas, not unimaginable — shocks.

Proposition two: “it’s the politics, stupid”. James Carville, Bill Clinton’s campaign strategist famously said that it’s “the economy, stupid”. The primacy of economics can no longer be assumed. Ours is an age of culture wars, identity politics, nationalism and geopolitical rivalry. It is also, as a result, an age of division, within and among countries.

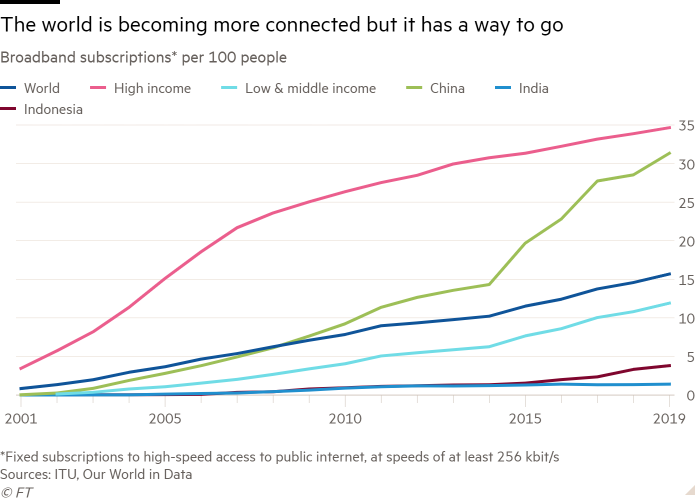

Proposition three: technology continues its transformative march. The Covid shock brought with it two welcome surprises: the ability to carry out so much of our normal lives online; and the capacity to develop and produce effective vaccines with amazing speed, while failing to deliver them equally. The world is divided in this way, too.

Proposition four: the political divides between the high-income democracies on the one hand and Russia and China on the other, are now deep. Prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the survival of an overarching concept of “one world” seemed at least conceivable, however difficult. But wars are transformative. China’s offer of a “no limits” partnership to Russia may have been decisive in Putin’s decision to risk the invasion. His war is an assault on core western interests and values. It has brought the US and Europe together, for the moment. It should be decisive for Europe’s attitude to China: a power that supports such an assault cannot be a trusted partner. The march towards totalitarianism in both of these autocracies must also widen the global split.

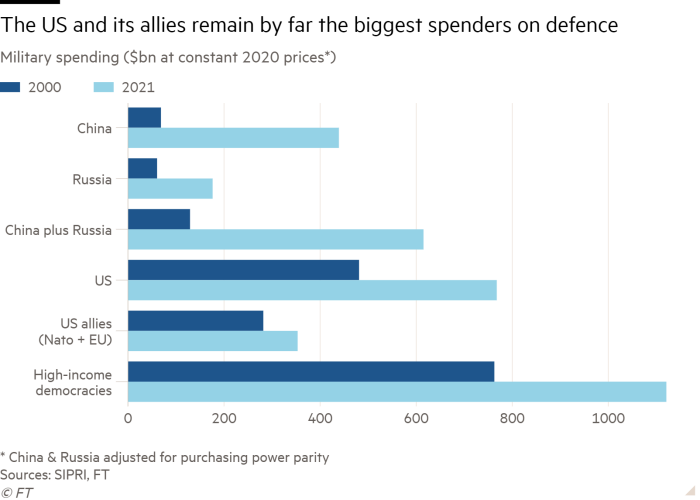

Proposition five: despite the rise of China, the west, defined as the high-income democracies, is hugely powerful. According to the IMF, these countries will still account for 42 per cent of global output at purchasing power parity and 57 per cent at market prices in 2022, against China’s 19 per cent, on both. They also issue all the significant reserve currencies. China holds more than $3tn in foreign currency reserves, while the US holds almost none. It can print them, instead. The ability of the US and its allies to freeze a large proportion of Russia’s currency reserves shows what this power means. Yet western power is not just economic. It is also military. How would Russia’s vaunted military have fared against Nato’s?

Proposition six: yet the west is also deeply divided within countries and among them. Plenty of its politicians were enthusiastic supports of Putin: Marine Le Pen was one of them. In Europe, Viktor Orbán is the most vocal survivor of this troupe. In the US, xenophobic authoritarianism — “Orbanism” — remains a leading set of ideas on the right. Donald Trump’s assault on the fundamental feature of democracy — a transfer of power through fair voting — is also very much alive. Many of these people view Putin’s nationalist autocracy as a model. If they get back into power, western unity will collapse.

Proposition seven: over the long run, Asia is likely to become the dominant economic region of the world. The emerging countries of east, south-east and south Asia contain half of the world’s population, against 16 per cent for all high-income countries together. According to the IMF, average real output per head of these Asian economies will jump from 9 per cent of that of high-income countries in 2000 to 23 per cent in 2022, mostly, but not only, because of China. This rise is likely to continue.

Proposition eight: the high-income democracies will have to up their political game if they are to persuade emerging and developing countries to side with them against China and Russia. Few countries like these autocracies. But the west has lost much support with its failed wars and inadequate help, notably during Covid. Most emerging and developing countries will try hard to stay on good terms with both sides.

Proposition nine: global co-operation remains essential. However deep the rifts become, we share this planet. We still need to avoid cataclysmic wars, economic collapse and, above all, destruction of the environment. None of this is at all likely without at least a minimum level of co-operation. Yet is that at all likely? No.

Proposition ten: The rumours of globalisation’s death are exaggerated. Americans are inclined to think their perspective is the global norm. Frequently, it is not, as on this. Most countries know that extensive trade is not a luxury but a necessity. Without it, they would be miserably impoverished. The more likely prospect is that trade will become less American, less western and less dominated by manufactures. Trade in services is likely to explode, however, driven by cross-border online interaction and artificial intelligence.

Proposition eleven: given the immense political and organisational challenges, the chances that humanity will prevent damaging climate change are slim. Emissions fell in 2020 because of Covid. But the curve remains unbent.

Proposition twelve: inflation has been unleashed in a way not seen for four decades. It is an open question whether central banks will maintain their credibility. High inflation and falling real incomes are a politically noxious combination. Upheaval will follow.

We in the west have to manage profound changes and lethal conflicts at a time of division and disillusionment. Our leaders have to rise to the occasion. Will they do so? One can only hope so.