This story was originally published by Inside Climate News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Emissions from the largest greenhouse gas emitters in the U.S. were down slightly in 2022, but thousands of industrial facilities with substantial emissions remain, according to the Environmental Protection Agency’s recently released Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program data.

Emissions from large industrial sources decreased by approximately 1 percent to 2.7 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2022, according to the annual update of emissions data released on Oct. 5. The data represents emissions from 7,586 industrial facilities across nearly all sectors of the economy and represents about half of all U.S. emissions.

An Inside Climate News analysis of the data highlights the top 10 greenhouse gas emitters as well as the top emitter for each of six leading greenhouse gases: carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorocarbons and sulfur hexafluoride, the world’s most potent greenhouse gas.

The assessment also identified top emitters of CO2 and methane, the two leading drivers of climate change, from each of several significant sectors of the economy for greenhouse gas emissions—refineries, steel mills and liquified natural gas (LNG) export terminals and underground gas storage facilities.

Some of the country’s largest climate polluters slashed their emissions in 2022 or said they are in the process of doing so, either voluntarily or by government mandate.

Moving off this year’s list was an underground natural gas storage facility, the Petal Gas Storage Compressor Station in Petal, Mississippi, a once-leading climate polluter that reduced its methane emissions by 91 percent from 2018 to 2022 and is no longer the highest emitter among gas storage sites. Other industrial facilities remained top polluters in 2022 but said they have reduced, or will reduce, their emissions by 99 percent or more by the end of this year. Still others reported their highest emissions yet in 2022.

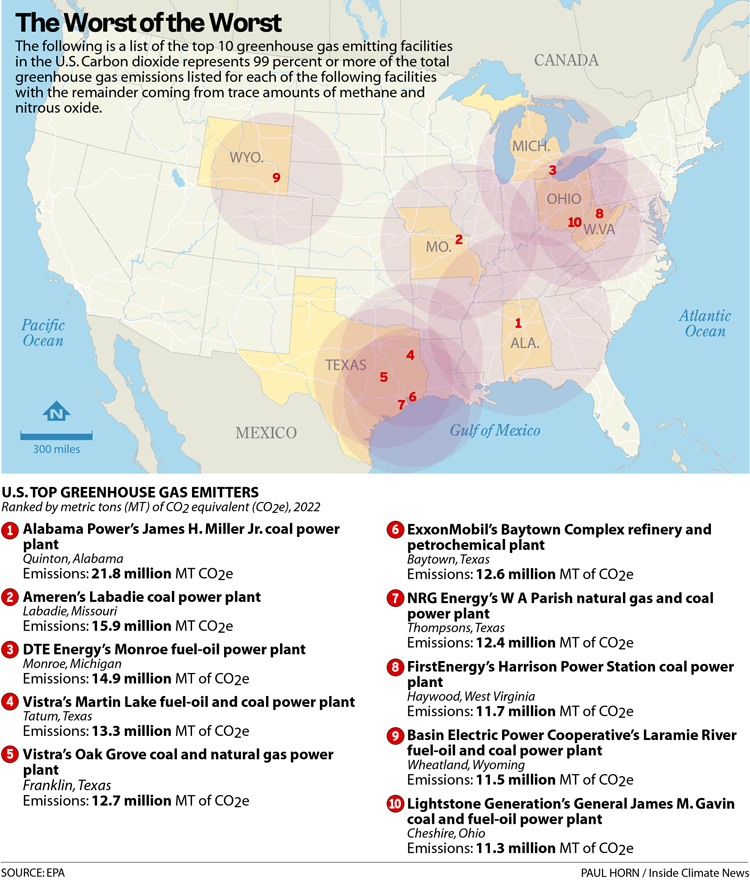

Here are the top 10 climate polluters in the nation, with their greenhouse gas emissions stated in metric tons (MT) as carbon dioxide equivalents (C02e):

1. Alabama Power’s James H. Miller Jr. coal power plant, Quinton, Alabama. Emissions: 21.8 million MT CO2e

2. Ameren’s Labadie coal power plant, Labadie, Missouri. Emissions: 15.9 million MT CO2e

3. DTE Energy’s Monroe fuel-oil power plant, Monroe, Michigan. Emissions: 14.9 million MT of CO2e

4. Vistra’s Martin Lake fuel-oil and coal power plant, Tantum, Texas. Emissions: 13.3 million MT of CO2e

5. Vistra’s Oak Grove coal and natural gas power plant, Franklin, Texas. Emissions: 12.7 million MT of CO2e

6. ExxonMobil’s Baytown Complex refinery and petrochemical plant, Baytown, Texas. Emissions: 12.6 million MT of CO2e

7. NRG Energy’s W A Parish natural gas and coal power plant, Thompsons, Texas. Emissions: 12.4 million MT of CO2e

8. FirstEnergy’s Harrison Power Station coal power plant, Haywood, West Virginia. Emissions: 11.7 million MT of CO2e

9. Wyoming Municipal Power Agency’s Laramie River fuel-oil and coal power plant, Wheatland, Wyoming. Emissions: 11.5 million MT of CO2e

10. Lightstone Generation’s General James M. Gavin coal and fuel-oil power plant, Cheshire, Ohio. Emissions: 11.3 million MT of CO2e.

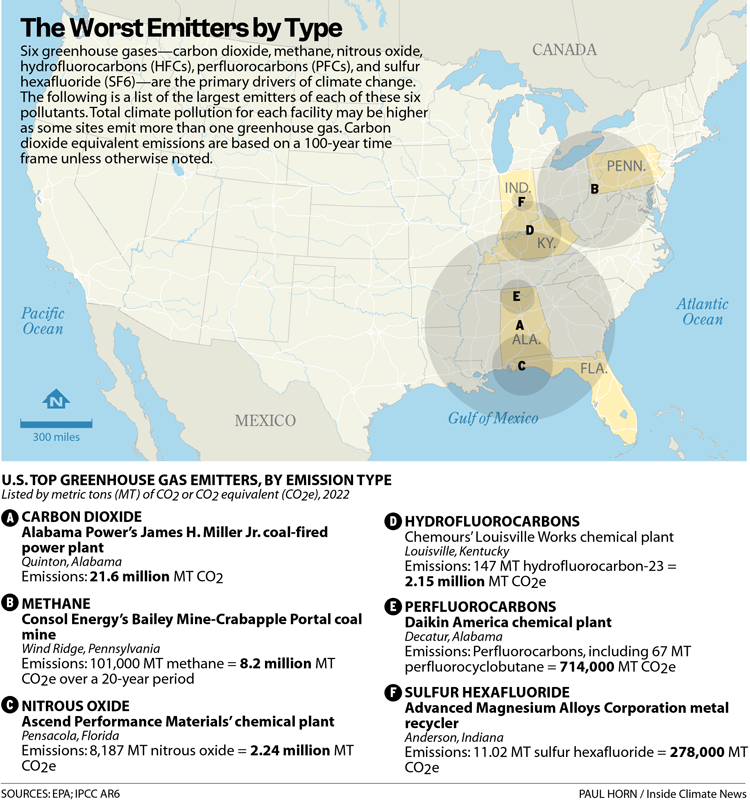

Here are the top emitters for each of the six leading greenhouse gases, listed from high to low in order of emissions:

A. Carbon dioxide

For the eighth year in a row, the James H. Miller Jr. coal-fired power plant in Quinton, Alabama was the largest climate polluter in the nation with 21.6 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions in 2022. Alabama Power, the plant’s owner, was one of the lowest ranked utilities in a recent assessment by the Sierra Club of 77 utility companies.

Teisha Wallace, a spokeswoman for Alabama Power, said nearly one-third of the electricity serving Alabama Power customers originates from clean fuel sources, primarily hydropower and nuclear energy. Wallace did not respond to questions about whether the company had any plans to retire the James H. Miller Jr. plant.

“Plant Miller is a key part of Alabama Power’s ability to dependably serve our customers,” Wallace said.

B. Methane

Consol Energy’s Bailey Mine in southwestern Pennsylvania was the largest point-source of methane pollution in the country for the second year in a row, with 101,000 metric tons of the potent greenhouse gas released in 2022.

Methane is 81 times more effective than carbon dioxide at warming the planet over a 20-year period, making the Bailey Mine’s emissions equal to 8.2 million metric tons of carbon dioxide or the annual emissions of 1.8 million automobiles.

Consol captures and incinerates additional methane that would otherwise result in further emissions. The company earns carbon credits for its methane emission reductions from the Pennsylvania Mining Complex, a group of mines that includes the Bailey mine.

One challenge coal mines face with methane capture is that much of the gas escapes through the mines’ ventilation systems in concentrations below 2 percent, far too low to be flared. Consol recently partnered with the U.S. Department of Energy to test a new, low cost method to destroy this low concentration methane gas. Company executives did not respond to a request for comment

C. Nitrous oxide

Emissions of nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas 273 times more potent than carbon dioxide on a pound-for-pound basis, were down 67 percent from 2021 at Ascend Performance Materials’ nylon plant near Pensacola, Florida following the installation of additional pollution controls at the facility. However, N2O emissions from the plant were still nearly twice that of any other facility in the country in 2022 and were equal to the annual greenhouse gas emissions of approximately half a million automobiles.

EPA says that the greenhouse gas emissions from the facility remain unverified for both 2021 and 2022 after the agency identified an error in the company’s report for each of the two years.

“All data reported to the EPA was and remains accurate,” Osama Khalifa, a spokesman for Ascend said.

Shayla Powell, a spokeswoman for EPA, said the company was notified of the error for the 2021 report in 2022 but “has not responded to EPA’s notification nor resubmitted” its 2021 data since November 1, 2022.”

Companies typically have 45 days to submit a revised greenhouse gas report to EPA, provide additional information about their reported emissions or request additional time to submit a revised report.

Powell said that violations of reporting requirements may result in civil penalties but added that “EPA cannot comment on potential or future enforcement actions related to this facility.”

Khalifa maintained the accuracy of Ascend’s reported data saying “we look forward to the EPA re-reviewing our submissions and correcting the status of our facility at their earliest convenience.”

A paper published in the journal Nature Climate Change in July flagged nitrous oxide emissions from adipic acid plants like Ascend’s as having “untapped” and “low-cost” emissions reduction potential and called for “urgent abatement” at such facilities. Nitrous oxide is an unwanted byproduct in the production of adipic acid, a key ingredient in nylon 6,6, a highly durable plastic used in airbags and car tires. Nitrous oxide emissions are also the leading, ongoing source of atmosphere ozone depletion after more harmful chemicals were banned in recent decades under the Montreal Protocol, an international environmental agreement.

Khalifa said Ascend continues to invest in reducing greenhouse gas emissions from all of its facilities with a goal of reducing 90 percent of companywide direct emissions by 2030.

D. Hydrofluorocarbons

Chemours’ Louisville Works was the highest emitter of hydrofluorocarbons in terms of carbon dioxide equivalents in 2022 with its release of 147 tons of HFC-23, a man-made, highly potent greenhouse gas that is an unwanted byproduct in the manufacturing of fluorinated chemicals. HFC-23 emissions from the Louisville Works were equal to the annual greenhouse gas emissions of approximately 480,000 automobiles.

EPA required U.S. chemical manufacturers including Chemours to use or destroy 99.9 percent of the HFC-23 it produces by October 2022.

Chemours subsequently sought and was granted a six-month extension of the October 2022 deadline. EPA spokeswoman Shayla Powell said Chemours now appears to be meeting the emission reduction requirements.

“EPA expects that Chemours has been meeting the 0.1 percent emission standard for HFC-23 since April 1, 2023, if not sooner,” Powell said in a written statement. “Chemours has reported required information concerning these HFC-23 regulations under [federal regulation] 40 CFR part 84 and EPA will assess compliance with the emission standard after the annual reports for calendar year 2023 are due.”

Cassie Olszewski, a spokeswoman for Chemours, said the company aims to reduce its “fluorinated organic chemical” emissions by at least 99 percent by 2030. “The project at Louisville Works is an example of another action Chemours has taken as we work toward achieving our company-wide goals,” she said.

E. Perfluorocarbons (PFCs)

A chemical plant owned by Daikin America in Decatur, Alabama emitted perfluorocarbons (PFCs) with a greenhouse gas equivalent equal to 714,265 tons of carbon dioxide in 2022, making the facility the largest PFC emitter in the country in terms of climate impact.

The Decatur plant’s releases of perfluorocarbons in 2022, equal to the annual greenhouse gas emissions of nearly 160,000 automobiles, was the highest reported for the facility since Daikin began mandatory greenhouse gas reporting to the EPA in 2011.

The primary climate pollutant from the plant was perfluorocyclobutane (c-C4F8), a greenhouse gas 9,540 times more effective at warming the planet than carbon dioxide on a pound-for-pound basis. The 67 tons of perfluorocyclobutane released from the plant in 2022 will remain in the atmosphere for 3,200 years.

Emissions of the gas “essentially permanently alter Earth’s radiative budget and should be reduced,” according to a study published in the journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics in 2019. Perfluorocyclobutane is a byproduct of hydrochlorofluorocarbon HCFC-22 manufacturing, which is used to make polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), or “Teflon,” according to the study.

“We are currently embarking on our next phase of PFC containment at the Decatur plant by capturing perfluorocyclobutane and other greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from process equipment and incinerating them,” Daikin America said in a written statement. “This work will start in 2024 and will be completed in 2025; targeting a 90 percent reduction of our largest GHG emission source (perfluorocyclobutane) by 2026.”

F. Sulfur hexafluoride

Metal recycler Advanced Magnesium Alloys Corporation (AMACOR), in Anderson, Indiana emitted more sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) than any other industrial facility in 2022. On a pound-for-pound basis, SF6 is 25,200 times more effective at warming the planet than carbon dioxide, making it the world’s most potent greenhouse gas. And unlike CO2, which remains in the atmosphere for roughly 300-1,000 years, SF6 sticks around, warming the planet, for 3,200 years.

AMACOR uses SF6 as a “cover gas” to create a protective barrier between the surrounding air and molten magnesium, which is highly reactive with oxygen and can burn if exposed to air. When the liquid metal cools, the sulfur hexafluoride is no longer needed. In 2022 the company released 11 tons of sulfur hexafluoride, climate pollution equal to the annual greenhouse gas emissions of 62,000 automobiles.

AMACOR is aware of the issue and has been working to transition to a different cover gas that is safe and effective for more than a decade. In 2008, the company hosted an EPA study that assessed potential alternatives. Now company officials say they are in the process of voluntarily transitioning to a new, climate friendly cover gas that they expect will reduce their carbon footprint by more than 99 percent by the end of the year.

“No one wants to use SF6,” Jan Guy, the owner and chief executive of AMACOR said. “One of the challenges for the industry has been finding a good alternative.”

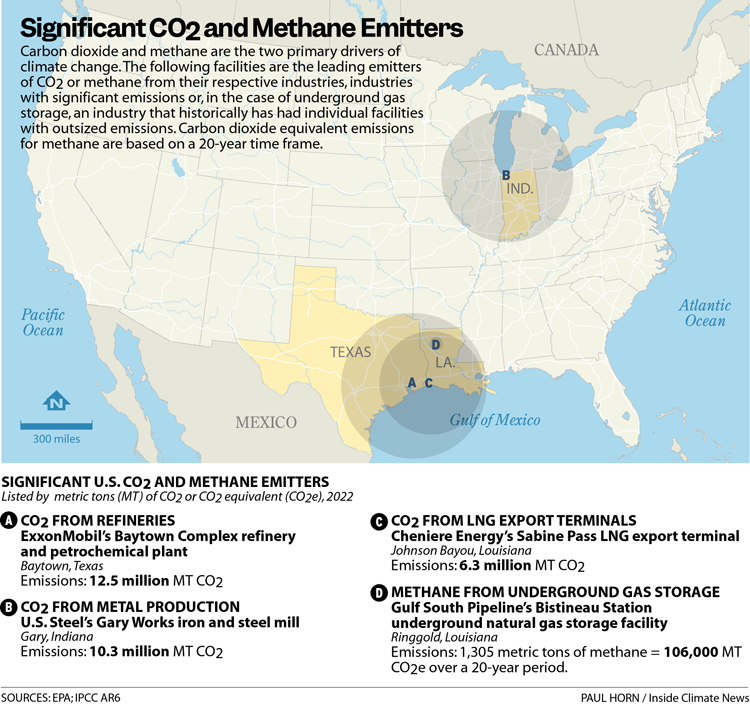

Here are the top emitters from important sectors of the economy for climate pollution—refineries, steel mills, liquified natural gas (LNG) export terminals and underground gas storage facilities:

Carbon dioxide from refineries

Refineries that convert crude oil to gasoline and other fuels are, like vehicles on the road, a leading source of climate pollution related to transportation. ExxonMobil’s Baytown Complex in Baytown, Texas had the highest greenhouse gas emissions of any refinery in the U.S. with 12.5 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions in 2022.

The pollution was the highest annual volume of carbon dioxide emissions from the refinery since ExxonMobil began mandatory emissions reporting in 2010. The 3,400-acre facility along the Houston Ship Channel released more than two times the greenhouse gas emissions of any other U.S. refinery. The climate pollution was equal to the annual emissions of 2.8 million automobiles, according to the EPA’s greenhouse gas equivalency calculator.

Lauren Kight, a spokeswoman for ExxonMobil, said the Baytown Complex emissions reported to the agency also include emissions from the company’s chemical plant and “olefins” plant co-located at the facility. Olefins are compounds used to make chemical products including plastics, synthetic fibers and rubber.

Kight did not respond to a request for an individual breakdown of greenhouse gas emissions from each sector of the Baytown complex. However, Kight said the company is working to reduce emissions at the facility.

“At Baytown, our emission-reduction plans include fuel switching to hydrogen, carbon capture and storage projects, renewable power purchase agreements and energy efficiency projects,” Kight said.

ExxonMobil’s proposed hydrogen project, in development with a consortium of companies, recently received up to $1.2 billion in federal funding.

Carbon dioxide from steel production

Steel manufacturing helps underpin the U.S. economy but is also a leading source of greenhouse gas pollution and toxic emissions that disproportionately impact environmental justice communities. U.S. Steel’s Gary Works, in Gary, Indiana was the largest greenhouse gas emitting iron and steel plant in the U.S. in 2022 with 10.3 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions, equal to the annual greenhouse gas emissions of 2.3 million automobiles.

Amanda Malkowski, a spokeswoman for U.S. Steel, said their Gary mill is the largest integrated iron and steel mill in the country and greenhouse gas emissions are proportional to the amount of iron and steel produced.

U.S. Steel announced an agreement with CarbonFree in March to capture and store 50,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide per year, about 0.5 percent of the facility’s total greenhouse gas emissions, beginning in 2025.

Carbon dioxide from LNG export terminals

Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) is often promoted as a clean-burning “bridge fuel” that can help developing countries wean themselves of dirty coal power while transitioning to renewables. Emissions of methane—the primary component of natural gas and a potent climate pollutant—throughout the fuel’s supply chain have largely debunked such “bridge fuel” claims. However, in addition to methane emissions associated with the fuel, LNG also has significant carbon dioxide emissions that go beyond the burning of the fuel by end users. To liquify natural gas, large amounts of energy are used to cool the gas to -260F, the point at which it becomes a liquid and takes up far less space. That energy typically comes from burning large amounts of natural gas, a process that results in significant carbon dioxide emissions.

Cheniere Energy’s Sabine Pass facility was the largest greenhouse gas emitting LNG terminal in the U.S. in 2022 with 6.3 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions.

Emissions from the facility, which Cheniere describes as “a marvel of modern infrastructure,” have climbed significantly nearly every year since the terminal came online in 2016 and are twice that of any other U.S. LNG terminal. Carbon dioxide emissions from the Sabine Pass terminal in 2022 equaled the annual greenhouse gas emissions of 1.4 million automobiles, according to the EPA’s greenhouse gas equivalency calculator.

Cheniere is now seeking federal approval to expand the Sabine Pass facility’s capacity by an additional two thirds of existing capacity and says the expansion would help to further displace the use of “coal and other more GHG [greenhouse gas] emission-intensive fuels” outside the U.S. Company officials declined a request for comment.

Methane from underground gas storage

Gulf South Pipeline Company’s Bistineau Station gas storage facility was the largest methane emitter among gas storage facilities in the U.S. in 2022, with 1,305 metric tons of methane released, equal to the annual greenhouse gas emissions of approximately 25,000 automobiles. The primary source of methane emissions reported from underground gas storage is from leaks in the compressors that pump gas in and out of the underground storage reservoirs.

The Petal Gas Storage facility in Petal, Mississippi was the largest methane emitter among underground gas storage facilities in 2021, but reduced its emissions by 91 percent from 2018 to 2022 by fixing or replacing leaky compressors. Both facilities are owned by the same parent company, Boardwalk Pipeline Partners.“We are currently in the process of making methane emission reducing enhancements to the equipment at Bistineau,” Jillian Kirkconnell, a spokeswoman for Boardwalk Pipeline Partners said. “This work is scheduled to be completed by the end of this year.”