[ad_1]

Inequality is on the rise again in the UK, with pay growing fastest for the highest earners, while inflation hits those on low incomes hardest.

Figures published last week by the Office for National Statistics showed average earnings in finance were 25 per cent higher in cash terms in March than the pre-pandemic level, outstripping the 15 per cent growth seen over the same period in mean earnings across the economy as a whole.

In two other high-paying sectors — professional services and IT — pay growth was almost as strong, at 21 per cent, and was driven by pay rises at the top, with the mean rising faster than the median.

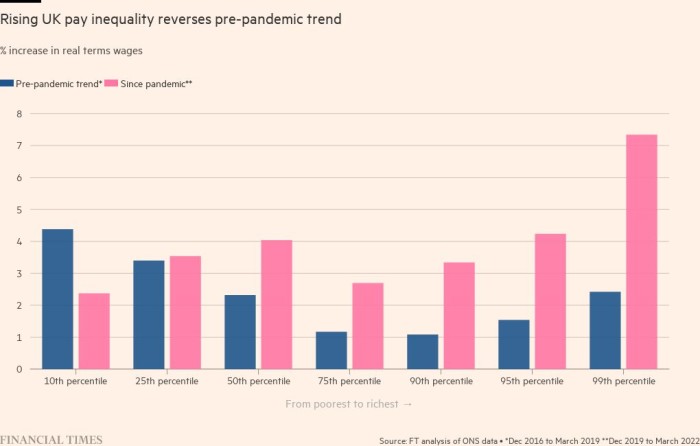

This means the highest paid have been better insulated than workers on low incomes against soaring inflation. The same figures, based on payroll data collected by HM Revenues & Customs — which include bonuses, show that for the top 1 per cent of employees, pay rose by more than 7 per cent in real terms between December 2019 and March 2022. For the tenth lowest paid, real terms wage growth was just over 2 per cent.

“For all the talk about labour shortages driving up low pay, the legacy of the pandemic may be greater earnings inequality,” said Xiaowei Xu, senior economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, whose analysis of the data shows that pay growth for the top 1 per cent started accelerating in October — even before a bumper bonus season widened the gap.

The skew is surprising, given widespread reports of labour shortages pushing up wages in low-paying sectors such as hospitality and care.

But it matches the picture emerging from other official data and from research published this week by the High Pay Centre think-tank. It found that executive pay was rebounding after a period of restraint, with the gap between chief executives’ pay and that of average employees set to widen.

The High Pay Centre, Equality Trust campaign group and the Trades Union Congress wrote to chairs of FTSE 350 companies on Wednesday urging them to freeze fixed pay for executives this year. It called for annual bonuses to be distributed among low paid workers to help them cope with “unprecedented increase to the cost of living”.

High inflation “will push many to the brink, not least those who are already at the sharp end of existing socio economic disadvantages”, the letter said.

The acceleration in pay at the top of companies is a sharp reversal of the trend in the years leading up to the pandemic, when earnings were growing fastest for the lowest paid, partly owing to rapid increases in the UK’s minimum wage.

Research by the Resolution Foundation think-tank, published on Wednesday, showed that the proportion of people on low pay, defined as earning less than two-thirds of typical hourly wages, fell to a record low of 13 per cent last year.

But the latest increase in the national living wage, which rose by 6.6 per cent in April, will not do as much as ministers had intended to raise the statutory wage floor towards median earnings, because average wage growth has also accelerated, while still failing to keep pace with inflation.

Figures published on Wednesday by the research group XpertHR showed the median basic pay increase awarded by employers in the three months to the end of April was worth 4 per cent, the highest since 1992, but still a full 5 percentage points behind April’s inflation rate of 9 per cent.

Xu said earnings data would not reflect the “full extent of the increase in inequality of living standards” because benefits were lagging inflation more than wages and households relying on benefits would therefore suffer a bigger real terms hit to their income.

The Office for Budget Responsibility, the independent fiscal watchdog, said on Wednesday that working-age benefits rates would be 6 to 7 per cent lower in real terms in 2022-23 than in 2019-20, while a 4.5 per cent fall in the value of unemployment-related benefits would be the sharpest in half a century.

This too is a reversal of the recent trend: overall income inequality fell during the pandemic in the UK, as in other developed economies, because the government made benefits more generous while also channelling financial support to workers who were furloughed.

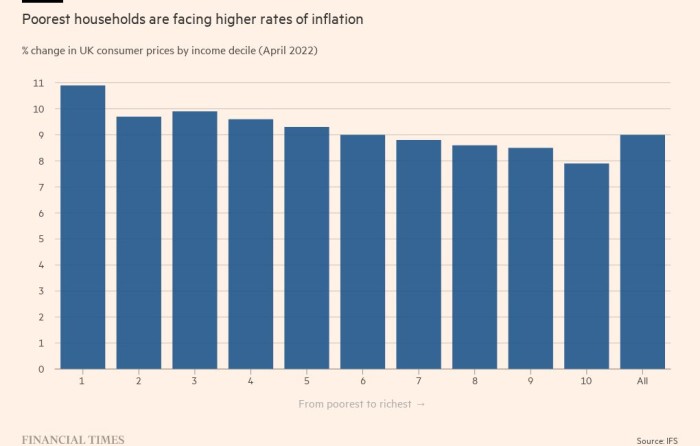

Meanwhile, the poorest households are experiencing a higher rate of inflation than those on middle or high incomes because they spend a higher proportion of their income on food and energy.

The IFS said last week that inflation — which hit 9 per cent in April on the official measure targeted by the Bank of England — was already running at 10.9 per cent for the poorest tenth of households, while the richest 10 per cent had seen prices rise by a more modest 7.9 per cent.

Xu said standard measures of poverty would not reflect this uneven effect, so would underplay the extent to which hardship was increasing.

[ad_2]

Source link