Santonicola, S.; Volgare, M.; Cocca, M.; Dorigato, G.; Giaccone, V.; Colavita, G. Impact of Fibrous Microplastic Pollution on Commercial Seafood and Consumer Health: A Review. Animals 2023, 13, 1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13111736

Microthreats

Microplastics have become an increasing concern all around the world as we discover the extent of their pollution. When we think of microplastics, an image of tiny, colorful pieces usually come to mind. However, we should set our eyes on a different type of microplastics: microfibers.

Microfibers have become a threat due to their widespread presence in marine environments, which leads to them ending up in commercial fish species, as they can be ingested. This means humans can be exposed through seafood consumption, be it from wild captured fish or farmed species.

But what type of microplastics are there? They are particles of different shapes (fibers, granules, spheroids, fragments, splinters, pellets, or beads) with dimensions between 0.1 μm and 5000 μm. They are highly persistent and can accumulate in different marine habitats. Specifically, fibers are found to be predominant in marine ecosystems, being more than 80% of the total items.

These microfibers can be synthetic, such as nylon or polyester, and natural, like cotton or wool. Natural microfibers are the most abundant ones in the environment, and most of the fibers come from textile industries.

And how are these microfibers generated? More than 600,000 fibers are released in a usual 5kg wash load of polyester textiles! Fishing nets, curtains, carpets and mattresses also play their part. Although, on average, 34.8% of microfibers in oceans are derived from the laundering of synthetic textiles, 28.3% come from the friction of tires.

What marine organisms are affected?

Microfibers can cause physical damage: blockage in the gut, low absorption of nutrients, disturbances in functions such as respiration… It can also cause consequences for biodiversity conservation, ecosystem services, and reduce food availability for the human population.

This is an important research topic, as fisheries and aquaculture are crucial activities that provide a significant part of the worldwide food supply, especially as global fish consumption continues to increase. As this topic rises in popularity and more studies are being made, it was revealed that there’s a considerable number of microfibers in commercial fish species, at levels higher compared to other microplastics. One of these studies investigated the microplastic exposure of different fish species in southern Taiwan, discovering that 96% of ingested microplastics were fibers.

However, the effects after ingesting microfibers may be different depending on the species and environmental conditions. Microfibers can be ingested by wild-captured pelagic and benthic fish (superficial and bottom fish), as well as farmed species. They consume it by foraging, for example mistaking plastic fragments and fibers for food, or incidental consumption from contaminated foods, sediments and waters.

In different studies, some of the fish that were found to be affected were the European hake (Merluccius merluccius) and the red mullet (Mullus barbatus). Fish aren’t the only ones affected; crustaceans are also contaminated. Some of them are the green crab (Carcinus aestuarii), which although only 5.5% of samples in an evaluation turned out to have ingested microfibers, they could transfer them to other organisms when they are eaten, like the eel (Anguilla anguilla). As for bivalve molluscs, fibers are the main microplastic shape found in mussels (Mytilus spp). Farmed bivalves contain more microfibers than wild ones, as they grow in coastal areas and on polypropylene lines.

Life in plastic isn’t fantastic

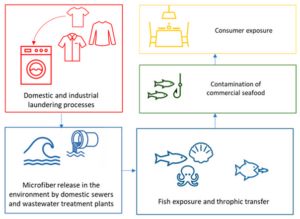

The human population can end up consuming microplastics through their seafood. Eating bivalves is what contributes the most, as people eat it whole. Not only bivalves have this effect, though; small pelagic fish, such as sardines, anchovies and sprats also expose humans to this type of contamination. Figure 1 shows how these microfibers arrive at our table.

Isn’t there any depuration process (purification of impurities or heterogeneous matter) before human consumption? Yes, they undergo a depuration before being sold, which helps eliminate microplastics that bivalves filter. Between 30 and 40% of synthetic microfibers were eliminated after 48h of depuration, although the process is less effective with small particles, as they accumulate more.

Exposure to these microfibers also depends on the type of diet. In regions such as East and West Africa, where fish consumption, including the gastrointestinal tract, is more common, accidental ingestion of plastics has raised concerns. A Korean person could be exposed to 212/particles per person annually through eating oysters, mussels, manila clams and scallops. European minor shellfish consumers could ingest around 1800 microplastics annually, and top shellfish consumers up to 11,000 microplastics annually.

What is concerning about this is that microplastics may carry potentially harmful chemicals or adsorb toxic pollutants from the sea. These could be transferred through the food chain with negative consequences for humans. They could also act as a vehicle for pathogenic microorganisms, but there isn’t a lot of information about this particular threat yet.

The future ahead

There are still a lot of questions that need answers, like the potential negative impacts on aquatic habitats, marine organisms and humans, which are still unknown. Long-term exposure to microfibers and their chemicals in fish and humans needs to be studied further. For this, data collection methods need to be standardized. Including other food groups like grains, vegetables and beef, as they are major sources of nutrients globally! The idea needs to be about promoting processing and cooking methods, not avoiding certain food categories. This issue can be addressed by involving clothing companies, consumers, municipal wastewater treatment plants, etc.

Weaving all these threads together could help us move into a future where new studies will keep microplastics at bay.

I have a degree in Sea Science from the University of Barcelona, Spain. My main scientific interests are about conservation and ecology, especially anything about marine invertebrates. I find them the most fascinating creatures on Earth, strange yet so familiar. On a visit to the beach as a baby, I learned to crawl by going towards the sea at full speed! I enjoy reading, drawing, and writing fantasy novels in my spare time.