You’ve heard “orthographic mapping” during discussions on literacy teaching and the science of reading. So, what is it? Short answer: Orthographic mapping is the mental process that happens when the brain learns to read words automatically.

What orthographic mapping is—and isn’t.

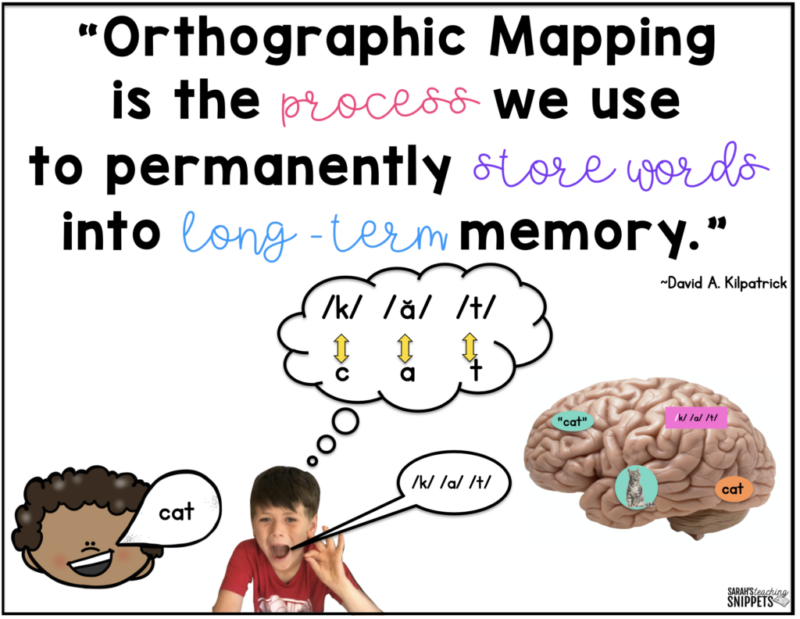

The idea of orthographic mapping was first proposed by Linnea Ehri in the 1970s. Other notable reading researchers, like David Kilpatrick, echo its importance. Orthographic mapping is what happens when different processing systems in the brain work in concert to connect a word’s spoken sounds, written letters, and meaning. For instance, a student sees the letters “r-e-d,” links them with the sounds /r/ /e/ /d/, and calls up their knowledge of the color red. Once these connections happen enough times, the word is stored in the student’s long-term memory and they can read and understand “red” automatically.

Orthographic mapping is not memorizing the shape of words, or even the letters of a word in order. Young kids may first learn to recognize their names, or words like “mom,” “dad,” or “love,” by how they look, but this isn’t a sustainable pathway to fluent reading. It’s linking a word’s meaning, its sounds, and its letters enough times for orthographic mapping to occur that leads to reading.

Why is orthographic mapping important?

Understanding this key process in learning to read can help you support all students’ reading progress. It can also help you pinpoint interventions that a struggling reader might need.

When orthographic mapping happens successfully, words in print become instantly recognizable sight words—no conscious effort needed. This is what lets proficient readers read efficiently for learning and enjoyment. (Many confuse the terms “sight words” and “high-frequency words.” A sight word is any word a reader’s brain recognizes automatically. High-frequency words, commonly occurring words like “the,” “is,” and “was,” end up being priority sight words for beginning readers to learn because they occur so often in print.)

How does orthographic mapping happen?

Kids in the beginning stages of learning to read usually need many experiences decoding a new word before it’s truly mapped in their brains. We’ve all listened to a child laboriously read a word sound by sound, only to have to do it again (and again, and again) the next time that word comes up. Orthographic mapping of a word has only been achieved when a reader doesn’t have to go through that process anymore. Proficient readers usually need fewer exposures to a word before orthographic mapping happens for them. That’s good news, since by adulthood, most readers have between 30,000 and 60,000 sight words successfully stored in their long-term memories!

Can we teach orthographic mapping?

It’s important to know that there are no orthographic mapping “activities” as there are for other lessons, nor should you be designating a time for it on your classroom schedule. Rather, teaching and practice in three key areas promotes orthographic mapping:

- Phonemic awareness—the ability to hear and work with individual words in spoken sounds. This is important because readers have to be able to break spoken words into sounds to connect them to letters. Learn more at What Is Phonemic Awareness: A Guide for Teachers and Families.

- Letter sound knowledge—knowing automatically how each spoken sound can be represented with a letter or group of letters.

- Phonic decoding—effectively “sounding out” words by connecting written letters to sounds and blending them together. Check out What Is Phonics: A Guide for Educators and Families to learn more.

What is phoneme grapheme mapping?

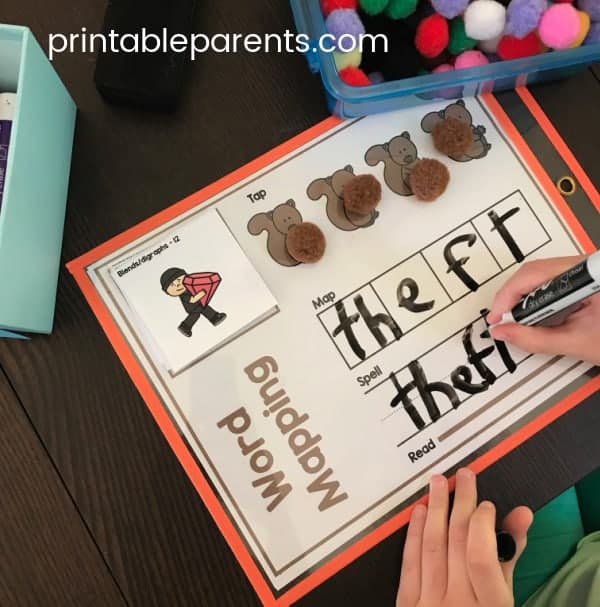

A common, research-backed way to encourage orthographic mapping when students are first learning to read is to guide them through phoneme grapheme mapping activities. These multi-sensory activities give kids practice listening for, isolating, and representing sounds in words. Check out Susan Jones Teaching’s video for a full explanation of using phoneme grapheme mapping activities with phonetically regular words.

Phoneme grapheme mapping is also an excellent way to jump-start kids’ orthographic mapping of a high-frequency word with an irregular spelling, or one that includes a spelling pattern they haven’t yet learned about. For instance, the most effective way to teach a new reader the word “said” isn’t getting kids to memorize the letters. Instead, get them to listen for and isolate the three sounds /s/ /eh/ /d/. Then talk about how in this word, “ai” spells the middle sound. (Want more tips on teaching high-frequency words? Check out our list of 55 Sight Word Activities That Work.)

What books support orthographic mapping?

Decodable books are an important way to encourage orthographic mapping for new readers. They support the sound-symbol-meaning connections that lead to mapping of words in kids’ brains. While tons of schools still have leveled books, teaching kids to guess at words based on context or sentence structure doesn’t have the same power.

Decodable text gives newer readers plenty of chances to practice linking letters with spoken sounds because it’s designed to only (or mostly) include words with spelling patterns kids have already learned. So, if you’ve only taught CVC (consonant-vowel-consonant) words, those are the words a decodable text would ask kids to read. Decodable text series layer on phonics demands in an intentional sequence to progress with your phonics teaching. We recently discovered the decodable readers by Charge Mommy Books. We love how they include both decodable stories and practice activities. They’re great for small groups or at-home practice.

Want to learn more? Don’t miss:

How To Choose the Best Science of Reading Curriculum

Helpful Science of Reading PD Books for Teachers

How To Set Up a Sound Wall in Your Classroom

What Is Reading Intervention? A Guide for Educators and Families