This past weekend I played a beta version of Mortal Kombat 1. I was part of an “online stress test” organized by NetherRealm Studios so the team could prepare the servers ahead of the game’s official launch. To quickly sum things up: So far, so good.

Mortal Kombat 1 (the number is part of the title) is the twelfth official Mortal Kombat and the second reboot of the overarching story. Set to launch on PC and all major consoles on September 19, it seems, from my view, to be taking a “back to basics” approach. As the first game in the new timeline, it is largely set in Earthrealm. There is room to get visually crazier, in future installments, once the Outworld and the Netherrealm come into play.

A return to Mortal Kombat’s roots

The beta let us test the single-player mode, via an abbreviated Klassic Tower, and play the game’s online versus with a subset of the final cast. The two locations on offer had both night and day variants.. The beta offered no training mode or space for you to test out your moves and combos so you needed to learn “on the job,” although there was an accessible command list for anyone who was experiencing Mortal Kombat for the first time.

My impressions are positive overall, even if the game doesn’t take any wild risks or make any mind- blowing innovations. Everything—even the gameplay aspects new to the franchise—have been done earlier by other fighting game franchises. But it’s done here with a rare sort of polish. The movement feels a bit slower, but it’s as though the developers are laying long-term groundwork for what’s to come—not only for this game, but for the inevitable sequels in the years ahead.

And from that standpoint, this is a very sturdy foundation, upon which there’s plenty of room to grow and elaborate. The core gameplay feels solid, and the characters have a sense of weight and deliberateness to them—a triumph of substance over sizzle.

The online response to the beta has also been positive, especially concerning the new “Kameo” system. You choose your fighter on the character select screen, and then you choose an assist partner, who can jump in and out of the fight on command to execute special moves. Timed correctly, these Kameo assists can interrupt an opponent’s offensive, cover a hole in your defense, or even extend a combo. A move that is unsafe can be made safe with an assist, forcing the opponent to continue blocking instead of being able to punish.The great number of main fighter and Kameo fighter pairing possibilities—especially with the final game’s eventual full roster—feels endless. You and your opponent will need to adjust to numerous variables, on the spot in real time, to emerge victorious.

The majority of the online buzz, post-beta, has been about the high amount of damage possible off of one combo—some balancing can fix this—and the return of “Quitalities,” first introduced in Mortal Kombat X. If your opponent rage-quits midway through a match, their character will either break their own neck or explode into bloody viscera, awarding you the win.

But you know what people aren’t talking about? Oddly enough, it’s the game’s Fatalities. Fatalities—arguably the single most famous aspect of the entire Mortal Kombat franchise—have been quietly shuffled to the background. I’m a longtime Kombatant, beginning with the Super Nintendo’s port of Mortal Kombat II in 1994. So for me, it’s especially jarring to see this shift in priorities. But it’s not entirely unexpected either. I think it’s indicative of a larger desire on the part of the developers at NetherRealm, first apparent with Mortal Kombat X, to be taken seriously by the larger fighting game community. They want the modern-day MK series to be respected for being more than just the sum of its gory parts.

A brief history of punching off your opponent’s head

In the original Mortal Kombat (1992), Fatalities were, at least in comparison to what was to come, simple and straightforward. Johnny Cage would uppercut his opponent’s head off. Raiden would blow up his opponent’s head with electricity. Kano would pull out his opponent’s beating heart and hold it aloft. But this pixelated violence was more than enough to act as the catalyst for a Senate hearing, which indirectly led to the creation of the Entertainment Software Ratings Board (ESRB) ratings system that video games still use.

By Mortal Kombat II (1993), the developers had abandoned all pretense of being realistic. Liu Kang turned into a dragon and bit his opponent in half. Kung Lao bisected his opponent lengthwise. Several of the Fatalities ended in an explosive shower of innards and blood. And each fighter had multiple finishers: two Fatalities, one Babality, one Friendship, and inputs for three different stage-specific Fatalities.

Mortal Kombat 3 continued this trend of self-aware, overblown mayhem. Kabal showed his hideous face to his opponent, whose soul became so frightened that it abandoned its body. Liu Kang crushed you with an original Mortal Kombat arcade machine. And Animalities—long-rumored in Mortal Kombat II—made their debut.

Two things stand out to me from this original trilogy of MK games. First is that each character had unique inputs and conditions that had to be met for the finishers to even work. The joystick / button inputs were one thing, and the spacing from the opponent was another. But some finishing moves demanded additional prerequisites. A Friendship finisher in Mortal Kombat II could only be performed if you won the last round using only kicks. Mortal Kombat 3 made the conditions even more overwrought, in that you had to grant the opponent a “Mercy,” which gave your opponent some extra life, before you could execute an Animality.

Second, the inputs for these Fatalities were not universally known or publicized. You had to buy a strategy guide, or have a subscription to Nintendo Power, or rely on word of mouth. The way I learned how to do all the Mortal Kombat II Fatalities was by calling the Nintendo hotline, which offered to send you a printed tip sheet with all of the finishers listed on them. I remember poring over it when it finally arrived in the mail, like I was receiving dark secrets from the mysterious ether.

The relative inaccessibility of the classic games’ Fatalities’ created a sense of exclusivity; it was a secret handshake of sorts that you could even perform these moves and fulfill their conditions, especially in the company of others

Mortal Kombat has fostered this exclusivity in different ways over the years. 2006’s Mortal Kombat: Armageddon opted to make the Fatalities more skill-based. The developers did away with any sort of pre-rendered cinematic cutscene, and instead had the player perform a Kreate-A-Fatality—a series of well-timed moves that would cumulatively end in the opponent’s death.

In Mortal Kombat (2011), Mortal Kombat X, and Mortal Kombat 11, each character had two Fatalities. The developers only gave us the button combination for one Fatality and you had to spend in-game currency in the Krypt to purchase the second.They also, for the first time in franchise history, gave players a Fatality Training mode, which allowed you to practice the spacing and timing of the finishers, apart from the actual fighting. It was very helpful, though in hindsight, it may have removed some of the mystique and exclusivity of these moves, especially if there’s an entire mode dedicated to grinding them out.

Why Fatalities hit differently these days

And something unexpected happened over the past decade or so. Slowly, Fatalities began taking on a negative connotation within the online multiplayer community. Most players now view them as poor etiquette, because they are long and unskippable, and because everyone has already seen them many times. Instead, it’s considered good form to end the match as quickly as possible—with an uppercut or a sweep—rather than gloat and force the opponent to sit through a 15-second cutscene. An additional practical concern arose for YouTube streamers, as constant gory Fatalities could lead to their videos getting demonetized.

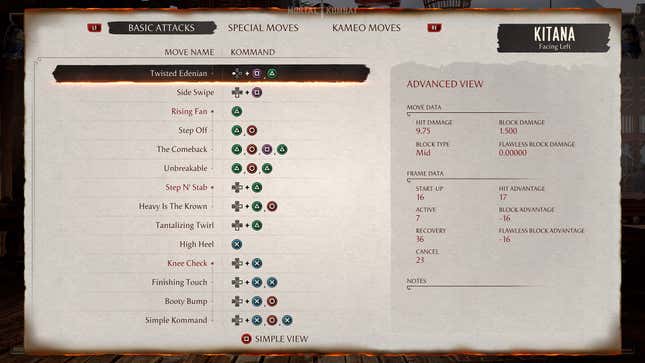

This is also around the time that Mortal Kombat made genuine strides toward being a deep, competitive experience. In Mortal Kombat 11, the in-game move list also showed frame data, so that players could easily see which moves and combos were safe on block, which ones were punishable, and how.

Which brings us to the Mortal Kombat 1 stress test this past weekend. Over the multiple hours I played, I lost a whole lot—certainly more than I won. But not a single person performed a Fatality on me; most opponents either swept or uppercutted me to finish the match, or simply punched me in the face.

Perhaps the ironic thing about this cultural shift is that the Fatalities are easier to perform than ever. For the first time in 20 years spacing no longer matters when performing a Fatality: You can stand anywhere on the screen to perform it. And the inputs to perform them are absurdly simple and shared between every character: it’s just Down, Down, and a button.

The original incentive to perform these executions—as a cool thing rarely seen in an arcade, or as a demonstration of skill and know-how—has been completely diminished, to the point that we’ve now come full circle. Fatalities are now easier to perform than the characters’ special moves but fewer people are doing them than ever before, despite the Fatalities themselves being much shorter, lengthwise, than in recent memory. What a strange set of circumstances.

Fatalities will never go away entirely. But it’s interesting to see how they’ve lost their cultural power and appeal over the years, not from any watchdog group or concerned parents, not from the developers folding to outside pressures, but from a fighting game community that’s simply over them, and cares more about the underlying game than a hyperbolized highlight reel.

And all of this bodes well for the franchise’s ongoing success in the greater fighting game community, as NetherRealm finally has a Mortal Kombat game in which the gore is its least-talked-about aspect. For the franchise’s long-time fans, that’s worth celebrating.