From the Summer 2023 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

As I write this essay, speculation continues to mount across social media, in newspapers, and even in scientific journals on whether the Ivory-billed Woodpecker continues to exist in the U.S. In part this reflects a flurry of recent unconfirmed reports suggesting ivory-bills may have been refound in a number of states, as well as a pending announcement by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on whether to declare the species officially extinct. Perhaps more than anything it reflects the iconic status of the Lord God Bird and its capacity to inspire the imagination of birdwatchers, especially in the U.S.

The last commonly agreed upon sighting was in 1944. In 2005 the Cornell Lab of Ornithology joined in an effort that produced eyewitness accounts and unconfirmed video and audio evidence of an ivory-bill in Arkansas, but despite extensive follow-up surveys it was not relocated. In 2021 the USFWS proposed delisting 11 birds from the Endangered Species Act due to extinction, including the ivory-bill, which has been the subject of continuing debate.

What new evidence has come forward in that time? To date, it comprises difficult-to-interpret photographs, videos, and sound recordings. As a recent New York Times headline put it: A Vanished Bird Might Live On, or Not. The Video Is Grainy. The new evidence certainly falls short of the visual or genomic evidence required to confirm ongoing existence of a species. This is not unexpected. Despite their size, ivory-bills are thought to be elusive, and the tracts of forests being searched are remote. Audio evidence of ivory-bills is surprisingly difficult to interpret because of the paucity of verified recordings, as well as confusing calls by other species or other sounds in the environment.

Nonetheless, for scientists such as myself, numerous pieces of relatively weak evidence do not add up to a compelling case. We need something that stands up to independent scrutiny.

The current evidence seems to suggest that USFWS will declare the ivory-bill extinct. If the USFWS decides not to declare the ivory-bill extinct at this time, it is a statement of hope that against all odds this magnificent bird may still persist. I strongly support the USFWS in making this difficult decision, but either way, the bigger picture that includes declared extinctions for the other 10 U.S. bird species is deeply sobering—not only because each one represents an irreplaceable loss, but because threats to birds and other species are accelerating at an unprecedented rate.

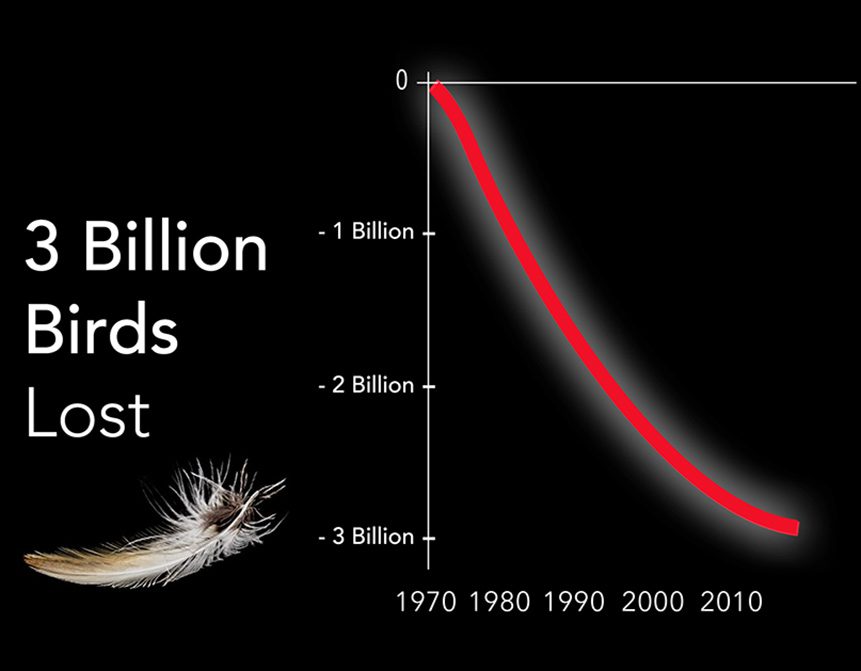

One in eight birds in the world today—more than 1,000 species—are threatened with extinction, and hundreds or even thousands more are in decline. This crisis is no longer restricted to the loss of a few species, but the collapse of entire ecosystems. Three billion breeding birds have been lost from the U.S. and Canada alone in the past 50 years, and the trends are eerily similar across Europe.

The ongoing search for ivory-bills illustrates a powerful conservation lesson: Once populations get down to a few individuals, or a couple patches of habitat, the challenges to bringing them back are immense. This is vividly demonstrated in Hawaii, where birds are in crisis, and where the USFWS recently declared another eight birds to be extinct. In total, 103 out of 142 Hawaiian bird species found nowhere else have now become extinct. If we are to be successful in bending the curve of loss for birds and biodiversity, we need to act much earlier in the extinction process.

The next five to 10 years will be critical to reverse the steep declines of many birds. I strongly believe our focus now should be on broad conservation actions rather than chasing charismatic species. We need to harness the passion catalyzed by the ivory-bill to save species and habitats while we still have the chance, before they too share the fate of this iconic species.

Ian Owens is the executive director of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.