The sight of a hundred thousand Purple Martins swirling across a South Carolina sky points up the enduring appeal of these gorgeous dive-bombing swallows.

From the Spring 2023 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

On a quiet August morning Captain Zach Steinhauser unties his Bennington tritoon boat from a dock on Lake Murray, a 50,000-acre reservoir about 15 miles from Columbia, South Carolina. The sky is blanketed by thick clouds, imparting a rather unseasonable monochromatic look to the popular recreational area.

“We’re at the tail end of the season, but they’re still there,” he says as we embark on a quick ride to Bomb Island. The 12-acre island—covered in shrubs, trees, and some shortleaf pine along its western shore—was used for practice runs by B-25 bombers during World War II. Today the island is used by another acrobatic flyer that’s the reason for our early-morning sojourn: Purple Martins.

North America’s largest swallow, Purple Martins first arrived on the island in 1988. Every year since (except for 2014, when they mysteriously deserted the island in favor of one 25 miles away), hundreds of thousands of martins have been roosting at this spot in the middle of South Carolina for a few short weeks from July through mid-August. Bomb Island is one of the largest roosting sites for the species anywhere, and by far the largest on the East Coast of the United States. Here the rather loquacious little birds can socialize, rest, and feed on the area’s plentiful insects before they embark on the next leg of their 3,000-mile migration to South America.

On this late-summer morning, what began as a few birds flying overhead soon multiplied into the tens of thousands. Taking off in unison, the tiny black flickers of each individual bird transformed into a monolith above. Contemporary accounts have compared the clouds of Purple Martins around Bomb Island to the ominous flocks in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, or the apocalyptic skies in Netflix’s Stranger Things. But there was nothing sinister about this aerial spectacle of martin masses; it was equal parts awe and action. Birds skimmed the water no more than an arm’s length from the boat; others scooped downward catching insects.

“To the right! To the right!! Here they come!” shouted Steinhauser over the cacophony of bird calls and wing flutters as another, even larger martin flock swooped directly parallel to the boat in synchrony. These massive takeoffs from martin roosting sites are so huge that they can be detected on weather radar.

“How awesome was that?” Steinhauser asked after the excitement concluded. Purple Martin is the one species that has enthralled him for years. While he carries many titles—boat captain, naturalist, photographer, master gardener—Steinhauser at age 30 has long fancied himself primarily as a filmmaker specializing in natural history.

“I always had dreams of becoming a wildlife filmmaker and game ranger in Africa,” he says, wearing his trademark green button-down shirt and backward-facing ball cap. Those dreams changed a bit after he contacted established filmmakers for tips on how to break into the profession. The overarching theme from each conversation: “Buy a camera and find local stories,” he says with a slight chuckle.

And so he did. He first discovered the Bomb Island martin roost as a 5-year-old boy in 1998, while on a family excursion. But he admits he didn’t think much about Bomb Island until he was a young adult obsessed with wildlife.

“I found the perfect story and it was right in my backyard,” he says.

Steinhauser is far from alone in his obsession with the little midnight-blue jet-fighter birds that streak through the air like daredevils and roost communally in extended families. The Purple Martin Conservation Association, based in Pennsylvania, estimates that more than 150,000 active martin colonies across North America are managed by people who maintain artificial nest sites. The PMCA calls these people Purple Martin landlords, and they really love their martins.

“Purple Martin landlord culture is unique,” says Robyn Bailey, project leader for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s NestWatch program.

“I think that people who put up these structures, they are also paying close attention to what’s going on,” Bailey says, noting that martin landlords in NestWatch track data on when the birds arrive in spring, how many eggs hatch, and how many chicks fledge. “This is part of what forms the bond.”

To help finance his budding career as a filmmaker, Steinhauser earned his United States Coast Guard captain’s license and began leading Purple Martin ecotours to Bomb Island in 2018. He soon learned that the species faces a number of conservation woes far beyond the shores of Lake Murray.

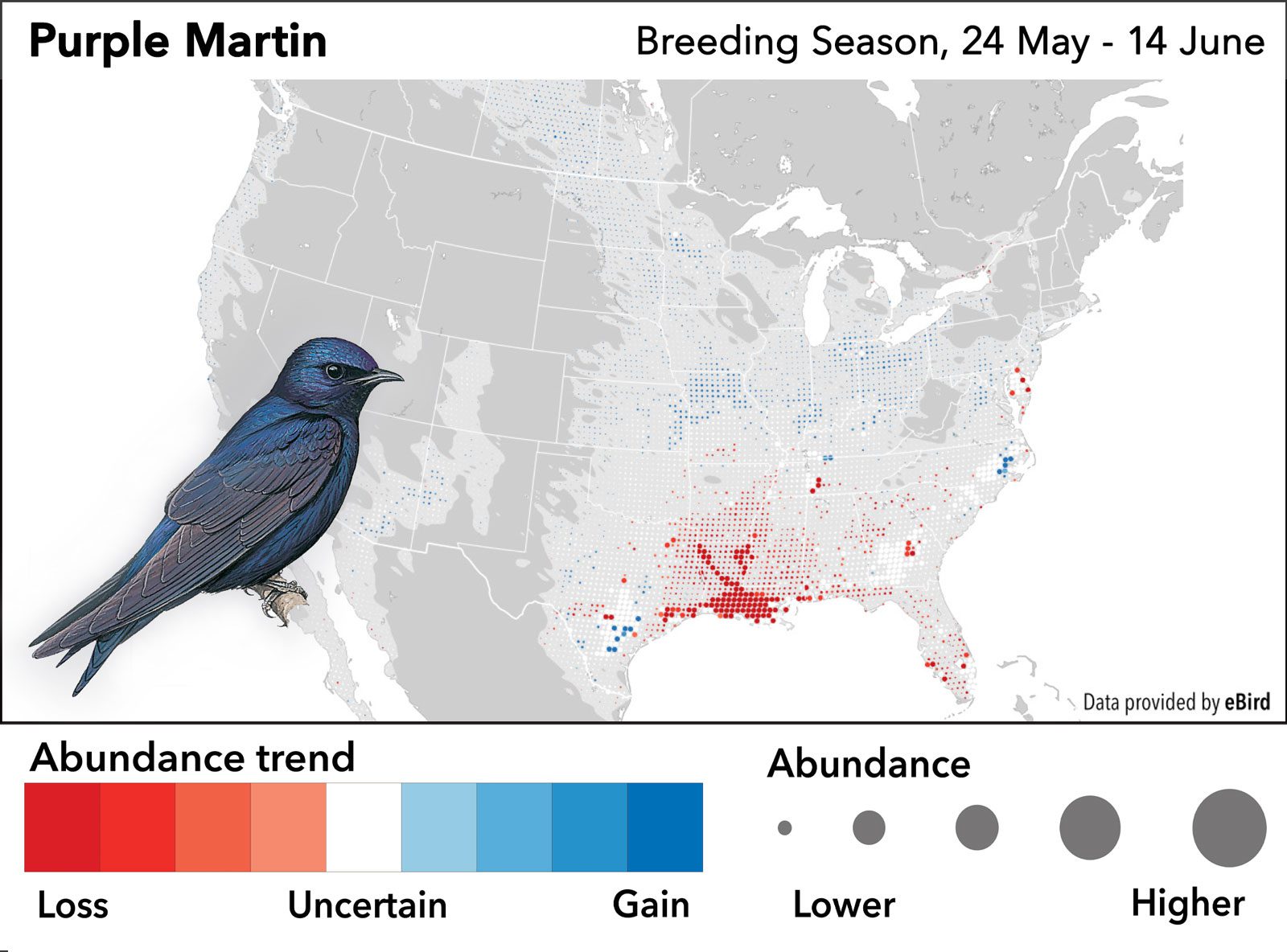

“Overall the general problem is a declining population, 25% to 30% decline over 50 years,” says Joe Siegrist, president and CEO of the PMCA.

The Purple Martin is an aerial insectivore, or bird that hunts flying insects on the wing, which makes the species vulnerable to disruptions in insect prey availability. According to Siegrist, a multitude of factors may be contributing to martin declines, including the direct loss of insects from the widespread use of insecticides and timing mismatches due to phenology shifts from climate change.

“Some local and regional declines are much worse, with near extirpation from areas of their historical range in New England. However, those areas can be bordered by areas of long-term increase,” adds Siegrist. “It’s definitely a complex system with different contributions of factors in different parts of the range. It’s a tall order for us to make sense of the data and determine the major factors at play for sure.”

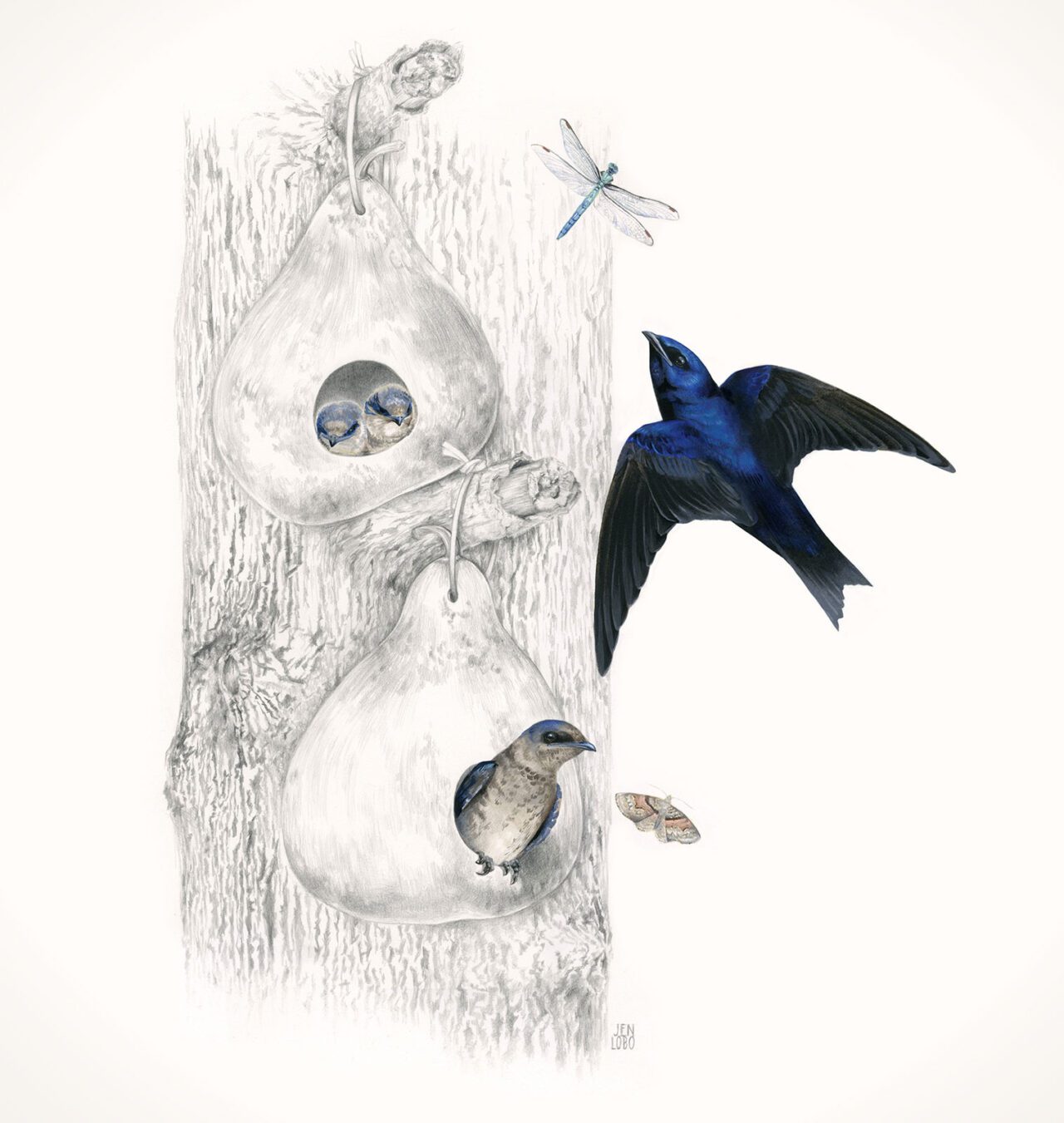

Unlike many bird species in trouble, breeding habitat is not thought to be a major factor in martin declines, because humans have had a net-positive effect in supporting Purple Martin breeding populations over the past century. Purple Martins are one of the few bird species that have shifted to nesting in artificial cavities. Martins never made their own nesting cavities; historically they used cavities created by other species, such as woodpeckers nesting along forest edges, or holes found naturally in cliffs.

Nesting cavity competition from invasive European Starlings and House Sparrows has long been a problem for all three subspecies of Purple Martins—Progne subis subis, which breeds across eastern North America; Progne subis arboricola, which breeds in western North America; and Progne subis hesperia, which breeds mostly in the Desert Southwest of Arizona and Mexico. Today almost the entirety of the eastern martin subspecies (subis) nests in artificial housings—about 95% of the total eastern martin population, according to Siegrist. The hesperia and arboricola subspecies still nest in natural cavities, such as saguaro cacti and dead snags.

Steinhauser visited Purple Martin colonies across nine states and traveled far south to martin wintering roosts in Brazil, armed with a Sony camcorder and Nikon DSLR camera, to make the documentary Purple Haze: A Conservation Film. The movie, which has been featured at five film festivals and three birding festivals in the past year and is slated for streaming release in 2024, includes Steinhauser’s conversations with biologists as well as the ultra-passionate people who make up one of birding’s most fascinating subcultures—Purple Martin landlording.

The practice of people providing housing for martins goes back centuries to the Indigenous cultures in North America, who would hang dried gourds for the birds to nest in. Kelly Applegate, a Purple Martin landlord and tribal member and commissioner of natural resources for the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe in Minnesota, says that having Purple Martins nest on a tribe’s territory provided security.

“Some tribes kept their meat and fish hanging near the gourds. If a bear showed up to feed on the food supply the tribe would hear the alarm calls,” he says.

Today, becoming a Purple Martin landlord requires an ample investment of money and time up front. A few artificial gourds and an aluminum pole may cost between $250 and $300, while some high-end Purple Martin houses with 12 or more nesting compartments can range up to $2,000. Every spring, houses must be properly cleaned before the birds return between April and May, and then maintained throughout the nesting season. It’s a good thing Purple Martin landlords are an enthusiastic bunch because martin landlording is not a transient hobby or a behavioral phase—it’s a lifestyle.

On a sunny, cold afternoon in early March, Jim Hottel walks with me to the T-14 model Purple Martin house he constructed in 2018 for the retirement community where he lives in Ellicott City, Maryland. The house is like a luxury apartment complex for 14 would-be nesting pairs of martins. Having previously built bluebird boxes, Hottel was convinced by a neighbor to build a Purple Martin house. Upon completion he was persuaded to serve as the inaugural landlord. But Hottel didn’t realize that—unlike bluebirds, in which only one nesting pair uses a box—martin landlording means serving a soon-to-be-booming colony of feathered tenants.

At first he had the laborious task of removing House Sparrow nests every few days. But when the first martins arrived, he became instantly hooked as he looked in to see how his new tenants were doing.

“It amazed me to see the parents waiting patiently, circling overhead, as we checked the nests,” he says.

Hottel was fortunate that he had three nests and 10 fledglings during that first season in 2019. By 2022, the colony had increased to 11 nests and 42 fledglings.

“This was the first time I interacted directly with wild animals in such an intimate way,” says an effusive Hottel, reflecting on the experience. “Seeing the chicks hatch and grow, and observing the parental oversight, was a wonderful experience.”

This early success is not typical. Puzzled, would-be landlords often express their frustrations on social media and internet forums. Even Steinhauser, who set up his first housing in 2018, did not have a nest until 2021. Now he has four active martin nests in six gourds, and he has installed gourd racks for 22 other landlords.

“It can take some time, but it helps to talk to other landlords,” Steinhauser suggests.

Kelly Applegate has been tending to a healthy, large colony of more than 30 pairs of breeding martins at his home in Mille Lacs for the past decade. But that’s not all; he also tends to martin colonies at his in-laws’ property, at a local park, and at a nearby John Deere dealership. And he has facilitated the establishment of five other martin colonies managed by the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe on tribal land.

Applegate, who also founded the Minnesota Purple Martin Working Group to create a strong network of martin colonies across the state, says the charismatic martins themselves provide the best sales pitch to get people into landlording.

“Get in front of an active colony and let the experience hit you,” Applegate says. “Your first encounter with the bird leaves an impression that you’ll never forget.”

Billy Ray Morgan is another martin landlord in Greenwood, South Carolina, whose enthusiasm and outreach have made him a promoter of new Purple Martin developments. His fascination with the birds began in 1970 when he was a 5-year-old boy, seeing the different types of birdhouses out the window of the yellow bus he rode to school. Morgan still remembers seeing farmhouses with gourds set out for resident martins.

“When I first saw Purple Martins flying around I was in awe,” he recalls.

Many years later in 1989, Morgan—by then an adult with an automobile—visited one of those farmhouses and spoke to the owner about becoming a martin landlord. He left with some advice and his first four gourds. A mere six weeks later, his first nesting pair of Purple Martins arrived, and he has been a martin landlord ever since.

In the decades that followed, Morgan has continued his friendly ways of strolling up to a door and striking up a conversation whenever he sees a home with Purple Martin housing. But these days he is concerned that younger people are not taking up the pastime, and he’s not alone.

A few years ago the PMCA conducted a survey to gauge the age of their membership and social media followers. Tara Dodge, director of outreach at the PMCA, says that most respondents were near or past retirement age: 54% of responses were from people aged 65 to 79, and 12% were 80 and above. The same survey found that less than 1% of respondents were between the ages of 25 and 34, and 4.6% were between the ages of 35 and 49.

Dodge says that, given how dependent Purple Martins in the East have become on humans to provide artificial nest sites, it would be catastrophic for the species if martin landlording were to stop.

“Even if one can’t host Purple Martins, it’s important to get people to care about them,” adds Dodge, who is a landlord herself. The PMCA is currently working on a national interdisciplinary curriculum that they hope to place in schools to inspire children and their families to become martin landlords, or even inspire the teachers to raise martin houses on school property.

Kelly Applegate says that in his work putting up martin housing all over Minnesota, he has seen people of every age, and from all walks of life, get interested in watching martins and taking care of them.

“You don’t need to be a certain way to care for these birds,” Applegate says. “You don’t need to be a conservationist, you don’t need to be a biologist, you just need a passion.”

At one point in his film, Steinhauser visits a massive Purple Martin wintering roost on an isolated island in the heart of the Amazon in Brazil. “The martins use this island similarly to the way they use Bomb Island, and multiple birds tagged [at a breeding site] in Pennsylvania were tracked to this particular site [in Brazil],” he says.

After his return home, Steinhauser learned that another martin at the roost in the Amazon had been previously tagged in Connecticut. It was a poignant moment for him.

“It goes to show how connected this world is, and the importance of conserving habitat for migratory birds on both sides of their ranges,” he says.

Back on that August day when I visited Steinhauser’s boat on Lake Murray, two guests accompanied us for a dusk ecotour to Bomb Island. The sky was filled with the brilliant shades of orange and blue, and we were joined by dozens of other boats bobbing and waiting nearby.

Steinhauser told us that the biggest surprise of his entire filmmaking experience came when a satellite tag that had been fitted to a Purple Martin in Erie, Pennsylvania, pinged just west of the Bomb Island Roost.

“I realized how important this island in my backyard was to this species that makes hemispherical migrations, and how they connect us to the world,” Steinhauser says.

While sharing more facts about the species, the small, dark form of a martin flew over the boat. Then a few more flew by. Then it was over a hundred birds. Steinhauser was quick to scan the sky.

“Here they come!” he shouted.

About the Author

Mark Hendricks is a freelance environmental writer, photographer, and faculty member in the Department of Psychology at Towson University. His next book, on the Central Appalachians, will be released in spring 2024 by Schiffer Publishing.