Featuring more than four hundred pieces of jewelry and other opulent objects, “Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity” opens today at the Dallas Museum of Art, the only North American venue for this highly anticipated exhibition, cocurated by the museum and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris.

Done in collaboration with the Musée du Louvre and with the support of the Maison Cartier, the show is remarkable from several angles. It’s a study of the design process, the nature of inspiration, and the evolution of style across centuries and continents. It marks, for many of us, a return to the museums of 3D objects after the COVID-19 pandemic flattened our experience of culture to the digital screen. And, notably, it’s a stunning achievement for the DMA and its director of six years, Agustín Arteaga.

During his tenure, the DMA has enjoyed a string of hits that fused popular appeal with diverse perspectives: Christian Dior’s fashion, Van Gogh’s olive groves, gold regalia from Ghana, and Mexican Modernist art featuring Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. The prestige of this Cartier project tops them all and can be attributed to Arteaga’s long-standing relationship with the 175-year-old luxury brand—he curated a Cartier exhibition at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City in 1999—as well as the DMA’s depth of Islamic art. The museum has held the Keir Collection, one of the foremost collections of Islamic art in the U.S., on a fifteen-year loan since 2014.

The new exhibition reveals how Islamic art exerted a formative influence on Louis Cartier as a collector and, more significantly, on his family business of jewelry and luxury objects, which was founded by his grandfather in 1847. “This topic was something that had been waiting to be explored,” Arteaga tells Texas Monthly. “It is crucial in the development of what is the Cartier style.”

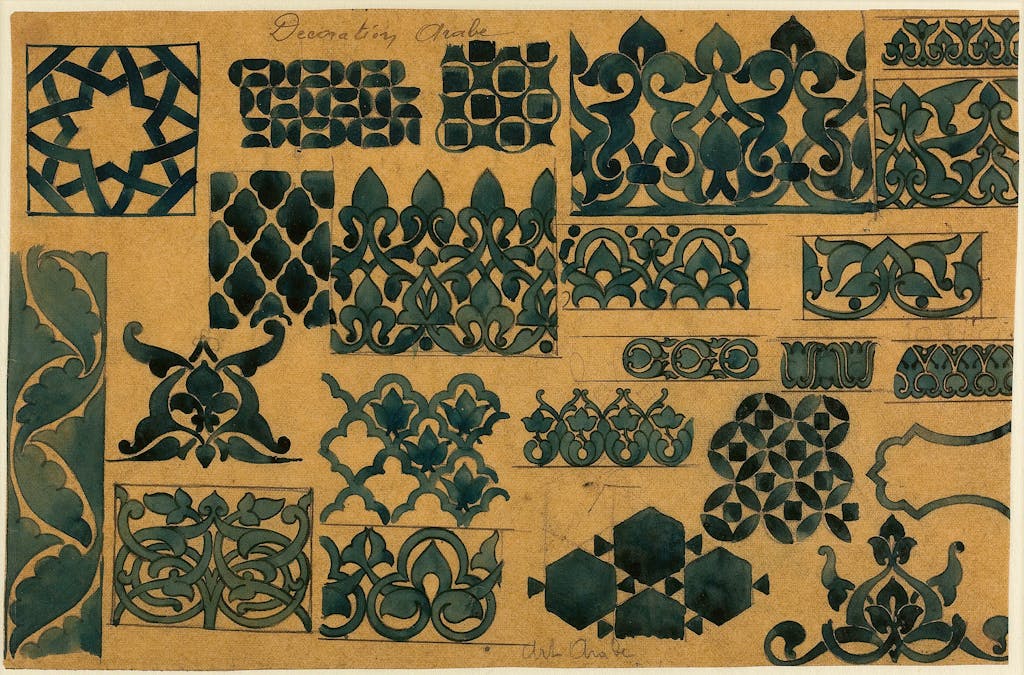

The show’s narrative opens on early twentieth-century Paris, the world capital of style, where colonialism has ignited fascination with art and design from Persia, Arabia, India, North Africa, and beyond. Tight geometric patterns impeccably rendered are one hallmark, but hardly the whole picture, says Sarah Schleuning, senior curator of decorative arts and design at the DMA and cocurator of this exhibition.

“You can explode one manuscript and see in there animals, turbans with ornamentation, incredible interlaced geometric patterns next to reciprocal patterns with finial shapes,” she says. “I think it was the density of ideas and the saturation of new colors that really was so stimulating and so exciting” to the Europeans.

Louis Cartier and his brothers looked to this world for materials, motifs, colors, and techniques that they could import and interpret to expand their style lexicon, which eventually coalesced into the codes of the house. For example, the jewel styles marketed as Tutti Frutti were derived from floral- and leaf-shaped cuts and settings found in Mughal India.

“Cartier is trying to look for new language to speak to the modern moment, but that moment continues to progress through time . . . so he looks back for influences and potential sources of inspiration, to make something that evokes the new in that moment,” says Schleuning, putting “modernity” into context.

In the evolution of the Cartier style, we recognize the broad shifts from nineteenth-century Neoclassicism (rehashing Greco-Roman antiquity) to art nouveau (shaping new materials into fluid, natural forms) to the sleek and structured art deco movement of which Cartier was a vanguard.

Perhaps it goes without saying: the jewelry in this show is jaw-dropping, heart-quickening, breathtaking.

And.

I found myself wrestling with the question of appropriation, because we must. My assessment after absorbing the show is that no single tradition could have given rise to Cartier style. Only Cartier, with its unique alchemy of inputs and individual creativity, could give us Cartier. This show is here to recognize and honor the Islamic influence, and it taught me a lot. Are recognition and honor overdue? Absolutely.

Renowned studio Diller Scofidio + Renfro designed the exhibition, injecting some clever technology. Extreme magnifications of select pieces (a red coral headband, an emerald brooch) and their construction feel immersive and slightly dizzying. A mechanical display morphs continually between a flat surface and a neck form, demonstrating how a complicated diamond necklace conforms to the body. The tech empowers the jewelry by making its intricate beauty more legible.

The pieces that I actually wanted to wear came in the fourth and final section, spanning the era after 1933, when Cartier appointed Jeanne Toussaint director of fine jewelry. With a firm command of Cartier’s modern vocabulary, she amped up the references, exuberant colors, and bold dimensions. The icon of this exhibition, appearing in all the promotional materials, is a 1947 necklace with amethysts, turquoise cabochons, and diamonds arrayed in a foliated bib. It’s excessive, and that’s the point. But it paves the way for colorful and chunky pieces that sync up with contemporary lifestyles and our boundless appetite for mid-century design.

“What we really wanted to focus on is how across time, media, and geography, artists are inspired to create new ideas,” says Schleuning. “They’re always in pursuit of the most modern ideas, and that’s personified by Cartier in the show. What you see are articulations, kaleidoscopes for creativity . . . and we shift that idea throughout the installation. I hope what people walk away with is this incredible idea of what it means to be inspired.”

“Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity” is on display through September 18, 2022.