Countries must exert greater control over gold imports and companies dealing in contraband supplies of the precious metal from the Amazon region should be punished, Brazil’s government has said.

Sonia Guajajara, the country’s first indigenous affairs minister, called for more support from foreign governments and industry in tackling illegal gold mining, a priority for the administration of leftwing president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

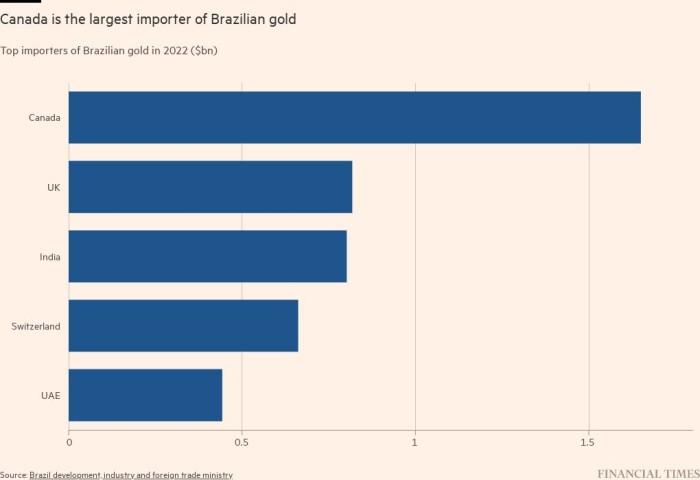

The top destinations for Brazilian gold are Canada, the UK, India, Switzerland and the United Arab Emirates. More than half the 97 tonnes of the country’s estimated production in 2021 showed evidence of links to illegal activities, according to a study by non-profit group Instituto Escolhas.

Guajajara said overseas corporate and state actors had a part to play in the clampdown against unlawful instances of informal or “wildcat” mining, known in Portuguese as garimpo. The practice has long been a leading factor driving invasions of protected indigenous lands and deforestation.

“The international community has a fundamental role in the fight against garimpo. Especially because the majority of companies [buying Brazilian gold] are from other countries,” Guajajara told the Financial Times. “It is urgently necessary to stop this path of gold . . . Governments need to regulate what enters their countries.”

Wearing a traditional headdress at her office in Brasília, the minister urged action to identify and impose sanctions on companies purchasing illicit gold. “Whoever is buying it should be penalised, because we will only be able to combat it when we actually get to the financiers of the mining.”

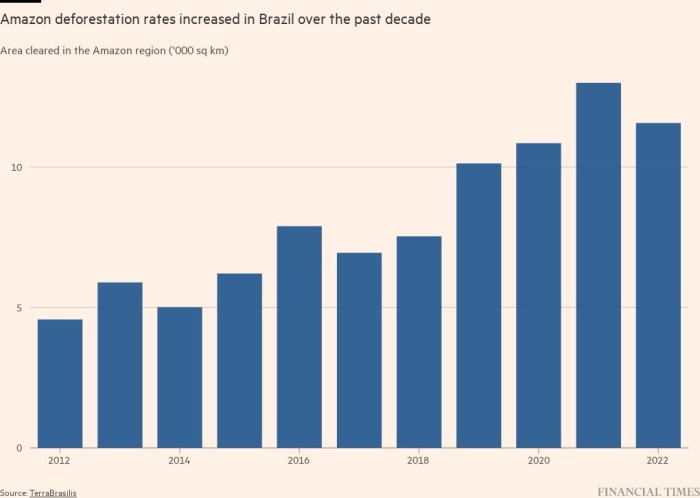

Wildcat mining, which is often associated with wider criminality, increased during the presidency of the far-right populist Jair Bolsonaro, whose administration weakened environmental protections.

Big businesses involved in the trade should make sure they are aware of the gold’s source as well as any links with ecological destruction or human rights violations, Guajajara said, adding that there needed to be greater consumer awareness too. “There is dialogue between various companies to reduce the damage and the impact of this gold, but it’s still not effective.”

The damaging consequences of illegal garimpo were underlined by a humanitarian crisis in the country’s largest indigenous reservation weeks into Lula’s presidency this year. Brasília declared a public health emergency for the Yanomami tribe, who number some 30,000 in an isolated rainforest area near the northern border with Venezuela, after a surge in malnutrition and diseases such as malaria blamed on incursions by illegal gold prospectors.

Small-scale wildcat miners traditionally worked with rudimentary tools to dig, pan and dredge, but the activity has grown in sophistication over recent years, with increased investment and the deployment of heavy machinery.

Campaigners accused Bolsonaro of giving the green light to criminal loggers and miners. He has rejected criticisms of his administration’s record on indigenous and environmental matters.

The total area occupied by informal mining in Brazil, which ranks among the top 15 gold producers, rose about a quarter between 2018 and 2021 to 196,000 hectares, according to environmental think-tank Mapbiomas. On indigenous territories, where mining is outlawed, activity doubled over the same period.

A longtime activist and the first indigenous person to hold ministerial office in Brazil, the 49-year-old Guajajara said protecting forests and biodiversity was a shared responsibility. “That is why it is essential that other countries also commit with financial support.”

Brazilian authorities say they have dismantled almost 300 camps on Yanomami land, where about 20,000 miners had entered, with military operations seizing boats, planes and equipment. Alongside the pollution of rivers with mercury, used to extract gold ore, locals have complained of harassment and sexual abuse by trespassers.

The crackdown coincides with other moves against the illegal gold trade in Brazil. Its revenue service is introducing electronic invoices for gold transactions, aimed at making it easier to investigate and uncover irregularities.

A supreme court judge this month suspended a legal practice that allowed gold buyers to accept the origin of the metal based on declarations made in “good faith” by the seller. He gave the government 90 days to enact new regulation.

Larissa Rodrigues, a researcher at Instituto Escolhas, said companies that purchase gold should disclose their suppliers and implement processes to trace its source. “If a country establishes more strict norms for due diligence, this would help much more than donating money,” she said.

The Brazilian Mining Institute, a lobby group representing industrial miners, said it was encouraging gold certification mechanisms in discussions with foreign states and banks.

“The mobilisation against illegal mining is advancing, but this criminal activity has taken root in the country,” said its president Raul Jungmann. “A joint effort is needed between private initiatives, Brazilian and foreign governments and NGOs.”

The World Gold Council, a trade body for large-scale gold mining, said: “We are progressing efforts to make it increasingly hard for illegally mined gold to enter the formal market.

“At the same time, we recognise the need to support responsible artisanal and small-scale miners and help them to access the formal gold market.”

Additional reporting by Carolina Ingizza