Millions of people worldwide have chronic kidney disease. Depending on the cause and on comorbid conditions, if left untreated it can progress to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). In the United States, care for ESKD is provided through Medicare — a federally run programme that provides health care mainly for older people. Most people with ESKD receive dialysis three times a week, indefinitely unless they get a transplant. Non-citizens — including undocumented immigrants — are usually excluded from policies that provide standard care for ESKD.

Access to care varies by state, with many people receiving dialysis only when they are critically ill — and they are almost entirely excluded from receiving a kidney transplant. At present, each transplant centre decides whether an undocumented individual qualifies for a transplant, and only California and Illinois provide medical coverage for kidney transplants for non-citizens.

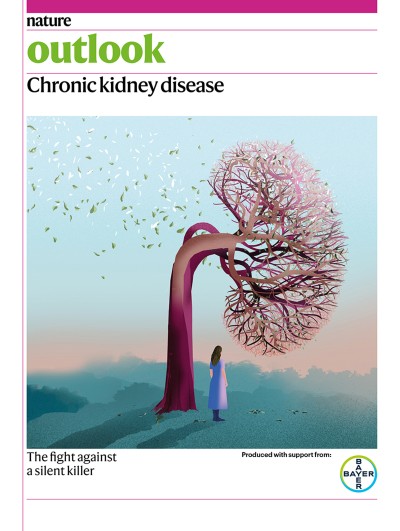

Part of Nature Outlook: Chronic kidney disease

In Illinois, for example, non-citizens qualify for a transplant if they have ESKD and they are in the Medicaid emergency dialysis programme (Medicaid is a US public health-insurance programme for people with low incomes). This policy was approved because transplantation is undoubtedly more cost-effective than urgent dialysis (saving nearly US$72,000 per person per year). The policy excludes people with kidney disease who are not receiving dialysis.

Despite enacting this more compassionate approach, Illinois has yet to see an increase in the number of transplants for undocumented immigrants. One of the reasons is that Medicaid no longer covers many non-citizens in need of emergency dialysis, which automatically disqualifies them from transplantation. Non-profit organizations, such as the American Kidney Fund (AKF) in Rockville, Maryland, cover scheduled dialysis care for those unable to afford it. AKF also covers transplantation costs, but coverage only includes the first year of care after transplantation. Policies continue to evolve, and one signed into law on 6 July 2021 allows non-citizens who receive kidney transplants to obtain coverage for immunosuppressive drugs and post-transplant care through a non-profit organization called the Illinois Transplant Fund in Itasca.

Some factors that hinder transplant coverage for undocumented individuals are closely related at the economic, ethical and policy levels. Current policies focus on how to protect and provide for US citizens first and avoid encouraging illegal immigration and transplant tourism. A federal law enacted in 1996 bans undocumented immigrants from receiving federal funds — a policy intended to remove an incentive for illegal immigration. Undocumented immigrants are also banned both from obtaining federal benefits such as Medicare and from purchasing private health insurance, even if they can afford it.

This lack of insurance is perhaps the most important barrier to transplantation. Medicare spends $27,000 on each transplant recipient each year after the initial cost of about $110,000. But Medicare coverage ends 36 months after a kidney transplant, at which point private insurance companies are responsible for the cost of immunosuppressive drugs. In addition, the possibility of deportation from the United States and, therefore, the potential lack of follow-up care in the country the individual is deported to could endanger the survival of the transplanted kidney.

Defenders of current policies say that there is a shortage of donor organs, and that allowing transplants for undocumented immigrants will worsen the situation. Furthermore, even though a 1986 federal law mandates emergency care for all regardless of their immigration status, solid-organ transplants are explicitly excluded because they aren’t considered emergency treatments. However, this argument ignores the fact that 60% of undocumented immigrants with ESKD have family members who could be living donors. States that provide ESKD care to non-citizens should consider transplantation for those who have living donors.

Strikingly, although undocumented individuals can’t receive organs, they can be organ donors. Organs donated by non-citizens accounted for 3.2% of the total in 2019, but an additional 9.8% of donors had an unknown citizenship status. This creates a troubling situation in which the organs of a large subpopulation can be donated but members of this population cannot benefit from the donation of others.

More from Nature Outlooks

Besides the ethical question raised by this asymmetry, there is also an economic argument for allowing undocumented immigrants to receive transplants. It is true that transplantation and post-transplant care are expensive, but they are more cost-effective than dialysis. Medicare pays around $77,000 for in-centre haemodialysis per person per year. People with ESKD live an average of five years after diagnosis. Assuming the average undocumented immigrant has a post-transplant life expectancy of eight years, kidney transplants are less costly than lifetime dialysis. Furthermore, undocumented immigrants represent a younger population who are, on average, physically independent, able to work and have fewer comorbidities. Undocumented immigrants collectively contribute an estimated $15 billion to state and local funds each year. These younger non-citizens with ESKD can return to their jobs (and therefore pay taxes) after a successful kidney transplant. To provide cost-effective care, states that already provide ESKD treatment to undocumented individuals should expand their transplant policies.

Globally, the approach to organ transplantation for non-citizens varies greatly. In the United Kingdom, foreign nationals can receive an organ if it is not assigned to a resident, but they must pay for the procedure. Most countries do not offer transplantation to the undocumented population. State-led efforts should continue to evolve to ensure equitable transplant access to undocumented individuals, especially given the part that they play in society as organ donors.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.