University buildings in Kharkiv, Ukraine, were damaged in a Russian missile strike earlier this month.Credit: Viacheslav Mavrychev/Suspilne Ukraine/JSC “UA:PBC”/Global Images Ukraine/Getty

A year into Russia’s war on Ukraine, its effects on global research collaborations might be starting to show up in the scientific literature.

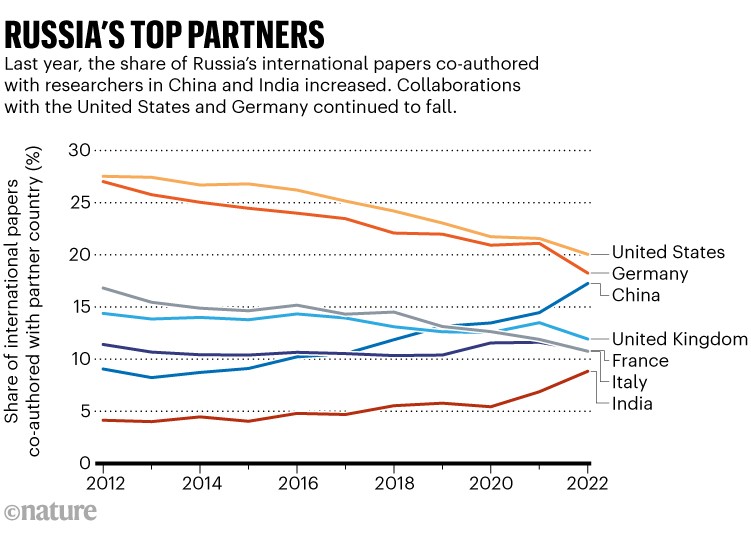

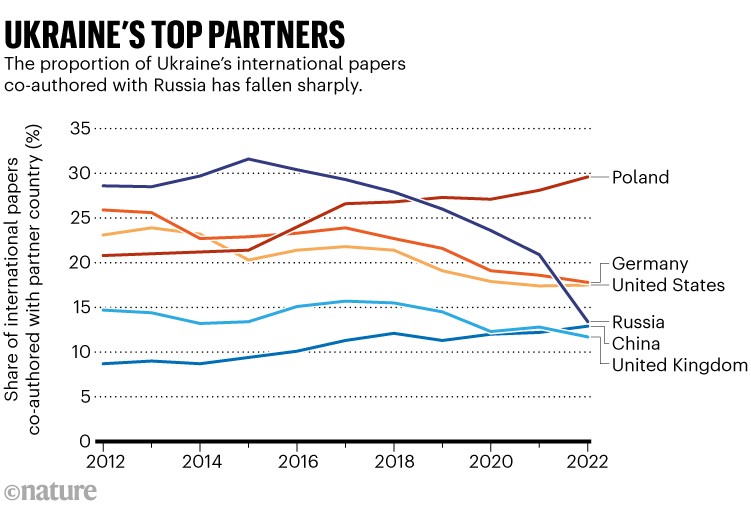

Nature analysed co-authorship patterns on papers in the Scopus database. The results suggest that, in 2022, an increased share of Russia’s internationally collaborative papers had co-authors from China and India, whereas the proportion co-written with US or German authors fell. Ukraine, meanwhile, has sharply reduced its scholarly ties with Russia, and seems to have increased research connections with Poland.

The fight to keep Ukrainian science alive through a year of war

The data available so far can only hint at possible changes, which will become more apparent later this year. Many of the papers published in 2022 were submitted to journals well before Western institutions halted scientific partnerships with Russia in response to the full-scale invasion, which began on 24 February. And databases of scientific papers will continue filling up their 2022 collections for another month or two, owing to routine indexing delays, so the raw numbers of papers will continue to increase. (Relative proportions of co-authorship are unlikely to vary at this stage.)

Co-authorship changes

Last year, just over a quarter of Russia’s papers and review articles — as recorded in Scopus — were internationally co-authored, a similar proportion to the year before. China is now close to overtaking the United States and Germany to become Russia’s top research partner, and India has soared up the rankings to seventh place (see ‘Russia’s top partners’). Among Russia’s top 25 collaborators, the only other countries that have increased their share of its international co-authorships in 2022 are Kazakhstan and Iran.

Source: Nature analysis of Scopus data.

Kieron Flanagan, a science-policy researcher at the University of Manchester, UK, cautions that co-authorships are an imperfect proxy for real research-collaboration patterns, and that it’s too early to draw conclusions from the available data. But he says that it does look like Russia has seen a long-term relative decline in research collaborations with Western countries, and this trend could have accelerated in 2022.

China is increasing its scientific co-authorship share with most countries except the United States, so its rising influence on Russia might not be particularly unusual, says Caroline Wagner, a science and policy researcher at the Ohio State University in Columbus. “The Russia–Ukraine conflict does not appear to have interrupted Russia and China’s cooperation,” she says.

In Ukraine, meanwhile, the proportion of papers with Russian co-authors fell sharply in 2022, and Poland is the country’s clear leading research partner (see ‘Ukraine’s top partners’). Around 38% of Ukraine’s papers in 2022 were internationally co-authored — a slightly higher proportion than in previous years.

Source: Nature analysis of Scopus data.

Nature found similar patterns in a parallel analysis of scientific papers in a different scholarly database, Dimensions (which differs from Scopus in its choice of journals to index). But according to the Dimensions data, Ukraine’s collaboration with Poland has not increased: it has remained at around the same level since 2021.

Cutting research ties

Many research organizations cut collaboration activities with Russia shortly after its invasion of Ukraine. Some funders, including those in Poland and Germany, strongly discouraged researchers from continuing to co-author papers with Russian scientists. The German Research Foundation (DFG) — the country’s main funding agency — said that this didn’t apply to work that had been completed or submitted to journals before the invasion, and a DFG spokesperson adds that the agency is not monitoring its recommendations or introducing punishments for researchers who go against them.

Ukrainian researchers pressure journals to boycott Russian authors

The research community has also discussed individual boycotts of Russian work — including in journals. International journals have generally not banned the consideration of Russian-authored work, and some researchers and journals have warned against indiscriminately isolating the country’s scientists. But at least one title, Elsevier’s Journal of Molecular Science, has said it will no longer consider manuscripts from scientists at Russian institutions. Its editor-in-chief, Rui Fausto, a chemist at the University of Coimbra in Portugal, says that the policy still stands, although Nature’s analysis found at least nine articles published in the journal that had Russian authors and had been submitted after the war began. (Fausto says that he is looking into them.)

The Ukrainian government has strongly discouraged collaboration with Russian researchers and publication in Russian journals, says Michael Rose, who studies the economics of science and innovation at the Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition in Munich, Germany.

The war has come in a general period where nations have become more aware of the competitive geopolitical aspects of research collaboration, Flanagan adds, with countries expanding export controls and introducing restrictions on overseas collaboration in certain activities that have been deemed sensitive to national security.