David Bowie’s vast collection of personal items — including flamboyant Ziggy Stardust costumes, handwritten lyrics and the Stylophone used in “Space Oddity” — has been donated to the UK’s Victoria and Albert Museum by the late rock artist’s estate.

The V&A will showcase more than 80,000 pieces, most of which have never been in the public domain, at its new hub in east London from 2025. It declined to give the value of the archive.

The pioneering musician, whose ideas also influenced film, art and fashion, was an inveterate collector of material relating to his creative process and output over six decades. He died from cancer in 2016.

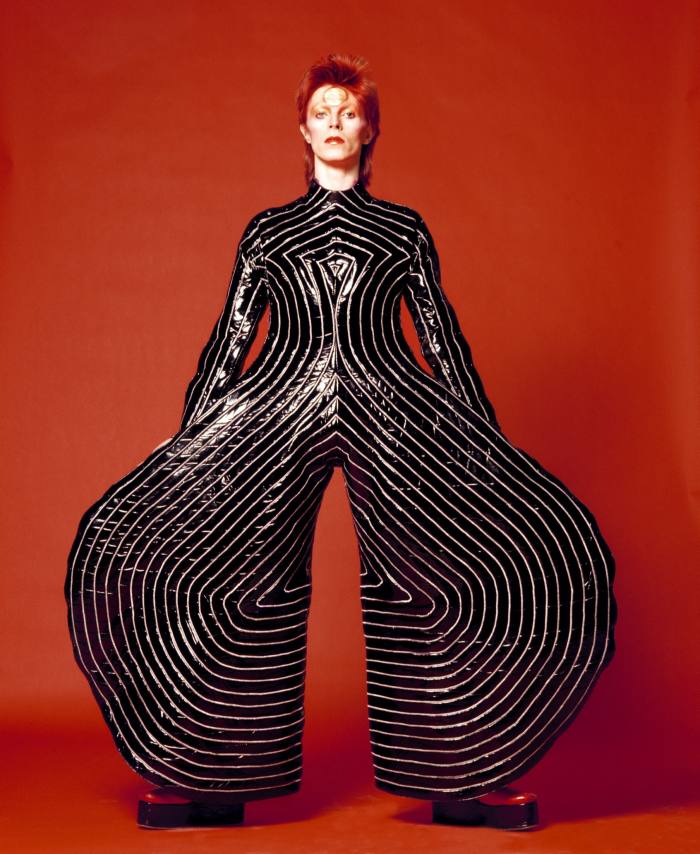

Bowie’s archive includes letters, set designs, thousands of slides, contact sheets and transparencies from photographers such as Terry O’Neill and Helmut Newton, as well as costumes made by fashion designers Alexander McQueen and Kansai Yamamoto.

There are also “intimate notebooks” filled with Bowie’s ideas, projects and musings, which the V&A said would cast new light on his creative thought process, as well as “cut up” lyrics, an experimental process of songwriting introduced to Bowie by the writer William Burroughs.

Guitars, amps and other equipment include Brian Eno’s synthesiser from Bowie’s 1977 album Low.

Kate Bailey, V&A senior curator for theatres and performances, said it was “unprecedented” for a global artist to preserve an archive on such a scale.

“He was keeping and documenting his creative process, whether that was an album cover, a song lyric, a stage set or a look . . . The fact that he had the vision to document and archive it is unbelievable,” she said, adding that Bowie was a lens through which to explore many cultural genres.

The trove of pop and rock history will be held and displayed in a newly created David Bowie Centre for the Study of Performing Arts at V&A East Storehouse in Stratford, east London, with items regularly switched over.

Due to open in 2025, the centre will be funded with £10mn donated by record label Warner Music Group, which owns Bowie’s songbook, and the Blavatnik Family Foundation.

Bowie had a longstanding relationship with the V&A, allowing it access to his effects to stage a temporary 2013 exhibition, David Bowie is, which became one of the museum’s most popular shows, drawing 2mn people across 12 international venues.

Bailey said the show had broken new ground with its multimedia display. Visitors heard different tracks by Bowie — delivered through German partner Sennheiser’s headphones — as they walked between rooms.

Bailey said the V&A had yet to develop a similar approach to displaying the archive, but added: “In the spirit of Bowie, we’ll need to do something that will follow his creativity and vision.”

She said detailed plans on how to display the collection were at an early stage but that the centre aimed to digitise objects and written documents as part of its conservation work and to increase access to the archive.

“His music is lasting. But when you start to see the sense of the visual journeys he went on and his personal research, that’s when it takes on this other kind of richness,” she said.