Alnahdi, K.A., Alali, L.W., Suwaidan, M.K., Akhtar, M.K. 2023. Engineering a microbiosphere to clean up the ocean – inspiration from the plastisphere. Front. Mar. Sci. 10.1017378, Doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1017378

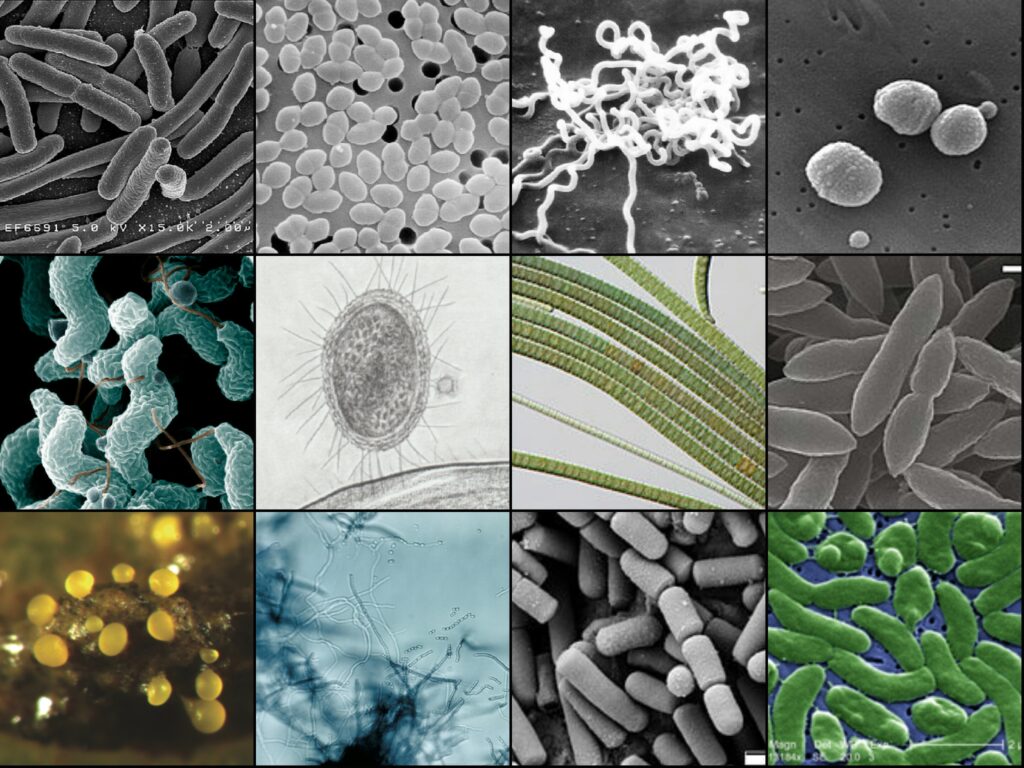

Plastic pollution in the world’s oceans presents a problem for marine life. Microplastics, which are small plastic pieces <5mm in size, may also have a negative effect on many animals. However, one organism that might be able to take advantage of the presence of microplastics in the ocean are bacteria. The “plastisphere” is a term coined in 2013 in a paper by Erik Zettler and colleagues to describe the community of microbial species that form on pieces of plastic. This community is often different from the microbial community in the surrounding seawater, or on other things floating in the ocean. After multiple decades of exposure to plastic, there is also evidence that some bacteria are evolving the ability to “eat” plastic – more specifically, use plastic as a source of energy. This poses an interesting question: could the “plastisphere” be used to degrade plastics in the ocean?

Researchers from the United Arab Emirates wrote an article exploring the possibility of creating a specific microbial community (a “microbiosphere”) in order to help clean up plastic pollution in the ocean. The researchers posed five design features that would need to be incorporated into this type of system.

First, there would need to be some sort of biodegradable material to support the microbiosphere – something that microbes could live on, but that would degrade in the natural environment. Second, the microbial community would need to be made up of a number of different bacterial species and be self-sustaining, and third, the bacteria would need to have some way of attaching to the plastics. These types of attachments in bacteria are typically either from cellular appendages (like flagella for example), or by bacteria making compounds that allow them to stick to surfaces.

Fourth, the bacteria that make up the microbiosphere would need to be able to degrade, or break down, plastics. Furthermore, since plastics are often created to contain chemicals, and certain chemicals will stick to plastic when it enters the marine environment, there would need to be microbes capable of breaking down those chemicals as well. And fifth, the microbial community would need to be made up of non-pathogenic, or non-disease causing, species. Some toxic microbes have been shown to attach to marine plastics, so the community created would need to prevent those toxic microbes from attaching to the microbiosphere.

Many questions still remain about how feasible this kind of strategy would be. How rapidly would the bacteria degrade plastic? Would it work across all ocean environments? Would the microbiosphere still keep degrading plastic after months? Years? How would the microbiosphere come into contact with marine plastic? Still, this train of thought represents a new way of thinking about how we can deal with plastic pollution in the ocean.

I’m a PhD student in Oceanography at the University of Connecticut, Avery Point. My current research interests involve microplastics and their effects on marine suspension feeding bivalves, and biological solutions to the issue of microplastics. Prior to grad school I received my B.S in Biology from Gettysburg College, and worked for the U.S Geological Survey before spending two years at a remote salmon hatchery in Alaska. Most of my free time is spent at the gym, fostering cats for a local rescue, and trying to find the best cold brew in southeastern CT.