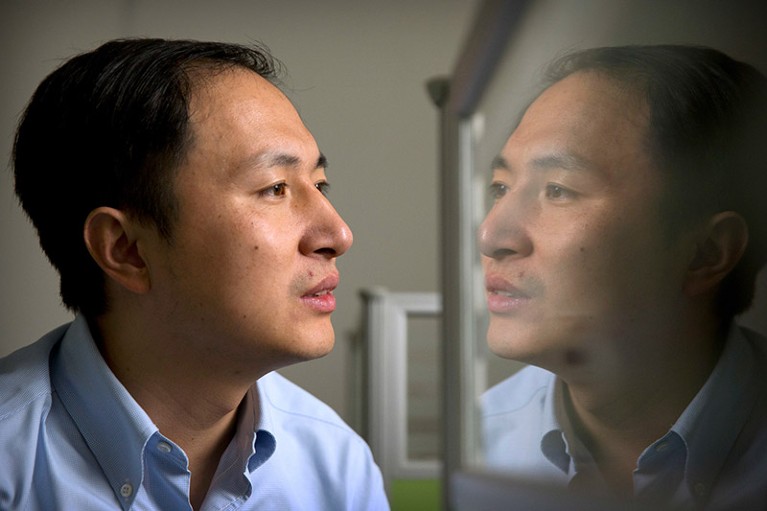

Biophysicist He Jiankui, who was released from prison last year, has declined to answer questions about his genome-editing experiments.Credit: Mark Schiefelbein/AP/Shutterstock

He Jiankui, the Chinese biophysicist who shocked the world by creating the first children with edited genomes, says the kind of controversial experiments he performed more than four years ago should be banned, but is otherwise refusing to speak about the work that landed him in jail for three years. He’s silence is frustrating some scientists, who say he should answer questions about his past research before publicizing his latest plans to use genome-editing technology in people.

On Saturday, He spoke at a virtual and in-person bioethics event that was promoted as “the first time that Dr. He has agreed to interact with Chinese bioethicists and other CRISPR scientists in a public event”. But during the talk, He did not discuss his past work and refused to answer questions from the audience, responding instead that questions should be sent to him by email.

“This meeting has been very disappointing, notably the failure of He Jiankui to answer any questions,” says Robin Lovell-Badge, a developmental biologist at the Francis Crick Institute in London, who attended the event.

“A publicity stunt like today shows he doesn’t have much credibility at least in the eyes of his peers,” says Eben Kirksey, a medical anthropologist at the University of Oxford, UK.

The CRISPR-baby scandal: what’s next for human gene-editing

Hours before the event, He wrote a tweet that he was not comfortable discussing his past work. “I feel that I am not ready to talk about my experience in past 3 years,” he tweeted. He also said he would no longer attend the University of Oxford in March for a series of interviews with Kirksey, and said that he would not be attending an international genome editing summit at the Francis Crick Institute, where researchers will discuss the ethics of germline editing, also planned for March.

Kirksey declined to comment on the status of the Oxford interviews, but says He needs to clarify details about the circumstances surrounding his past experiments. In 2018, the world learned that He had used CRISPR–Cas9 to edit a gene known as CCR5, which encodes an HIV co-receptor, with the goal of making the children resistant to the virus. He implanted the embryos, which resulted in twins and another baby born to separate parents. The parents had agreed to the treatment because the fathers were HIV-positive and the mothers were HIV-negative.

He’s experiments were widely condemned by scientists, and several scientific groups have since concluded that genome editing should not be used to make changes that can be passed on to future generations.

It is not known whether He’s previous work succeeded or left the children free from side effects. Without evidence of that, Kirksey remains sceptical about He’s future scientific plans.

Since being released last year from prison for violating medical regulations in China, He has revealed on social media that he has set up a not-for-profit research laboratory in Beijing focused on developing affordable therapies for hereditary diseases such as Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD).

He’s research plans

The weekend event was organized by the BioGovernance Commons initiative, monthly online meetings on ethical and regulatory issues between academics in China and thoseacross Europe, North America and Asia, and was hosted by the University of Kent. More than 80 researchers from 13 countries attended virtually, and He, together with some 20 academics and students, were at a venue in Wuhan.

He, who gave a 25-minute presentation in Chinese, with simultaneous English translation, briefly described his plans to develop a gene-editing drug for people living with DMD, for which he is currently raising funding from philanthropic organisations. He said he would not be accepting investments from commercial entities to ensure that the therapies they develop are affordable, and that an international ethics committee would provide guidance on the work.

He also said that “heritable embryo gene editing should not be allowed in human clinical practice, either in China or other countries.” Although genome editing on embryos destined for implantation is banned in China, he said the implementation of regulations on gene editing technologies still lacked clarity. “Scientific research must be subject to constraints of ethics and morality,” he said at the end of his presentation. But He spent most of his talk describing the basics of genome editing technology and its application in agriculture, infectious disease, diagnostics and human health.

Researchers who attended the talk were disappointed. “It bordered on being insulting to the conference organizers and the participants to have used up the time with details and information that were not relevant,” says Françoise Baylis, a bioethicist and professor emerita at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, Canada. Baylis said He gave little information about his previous and current research endeavours.

Anna Lisa Ahlers, a social scientist and China studies scholar at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin, commended He on agreeing to speak to the group but says his presentation fell short of scientists’ expectations. “From his talk, I would have gotten the impression that he is a salesman.”

He’s presentation and failure to engage with scientists at the event shows he has not considered the social and ethical implications of his research, which suggests that he is not ready to work on genome editing, says Joy Zhang, a sociologist at the University of Kent in Canterbury, UK, and one of the event organisers. “We don’t want another scandal where desperate patients will be exploited for ventures on experimental or even illegal therapies,” says Zhang.

Nature asked He to comment on criticisms about his talk from scientists. He responded by sharing a link to his earlier tweet.

Too much publicity?

Some researchers worry that interest in He Jiankui is diverting attention away from more important ethical issues around heritable genome editing. “This event puts the spotlight on He Jiankui — Will he apologize? Is he displaying remorse?,” says Marcy Darnovsky, a public interest advocate on the social implications of human biotechnology at the Center for Genetics and Society in Oakland, California. Instead, she thinks researchers should focus on discussing whether there is a medical justification for heritable genome editing.

Following He’s announcement in 2018, the US National Academy of Medicine, the US National Academy of Sciences and the UK Royal Society concluded in a 2020 report that gene editing technology was not ready for use in human embryos destined to be implanted. And in July 2021, a committee convened by the World Health Organization advised against the use of heritable gene editing. Some 70 countries prohibit heritable genome editing, according to a 2020 policy review1.