We are sailing along the front line of Antarctic climate change, a coastal vista of volcanoes and icebergs that used to be part of the Larsen Ice Shelf until global warming led a chunk the size of Rhode Island to disintegrate and further melting reduced it to a silver sliver. A penguin, perched on floating ice, watches our ship cruise by.

This is most likely the first boat, and we the first people, it will have seen. Le Commandant Charcot, the world’s most powerful non-nuclear icebreaker, is one of the very few vessels to have sailed these waters.

In my cabin, I’m dining with Peter Fretwell, author and scientist at the British Antarctic Survey and, right now, part of an expedition combining scientists and experts on fields ranging from climate change to oceanology with representatives from technology, business, media and the arts.

Fretwell is the expedition’s resident expert on penguins and a global champion for their cause. And the emperor penguin, his primary focus, has become both symbol and victim of Antarctic climate change. These birds breed on sea ice and thus are directly exposed to the impact of global warming. A few days earlier, a study published in the journal PLOS Biology projected that by 2100 up to 80 per cent of emperor penguin colonies would be quasi-extinct, meaning numbers would be reduced to such a level that the population is unable to sustain itself in the long term.

“Heart-breaking,” says Fretwell. “It’s a tragedy that most emperor penguin colonies have never seen humans and yet they are still being lost because of humans.” Seeing the regal, gold-cheeked parents and their fluffy chicks — familiar from countless Christmas cards and the animated movie Happy Feet — up close in their icy habitat, it is hard to hear the sad reality.

The implications of climate change, Fretwell underlines, go well beyond the penguin. “We may be in the most remote part of the planet, but what happens here affects the rest of the world, whether from ice melting and sea levels rising, or the circulation from the deep-water conveyor that starts here and drives many of the currents around the world,” he says.

The deadly blizzards that have been wreaking havoc in the US during our two-week voyage are just the latest example of extreme global weather. And, from this Antarctic vantage point, the prospects are troubling. “This year we have seen the worst Antarctic sea ice loss on record, and that follows on from the previous worst the previous year,” Fretwell explains. Evidence abounds. We sail past the majestic Murdoch Nunatak, one of a string of volcanoes once encased by icefields but now a lonely island.

“We are sailing into a bay that 30 years ago was covered by an ice shelf hundreds of metres thick. That all broke off and melted,” says Fretwell, sipping a glass of water. “That is happening along the Antarctic peninsula — faster and faster. Now we are starting to see those things happening not just on the peninsula but in other parts of East Antarctica, too. And that’s a real worry.”

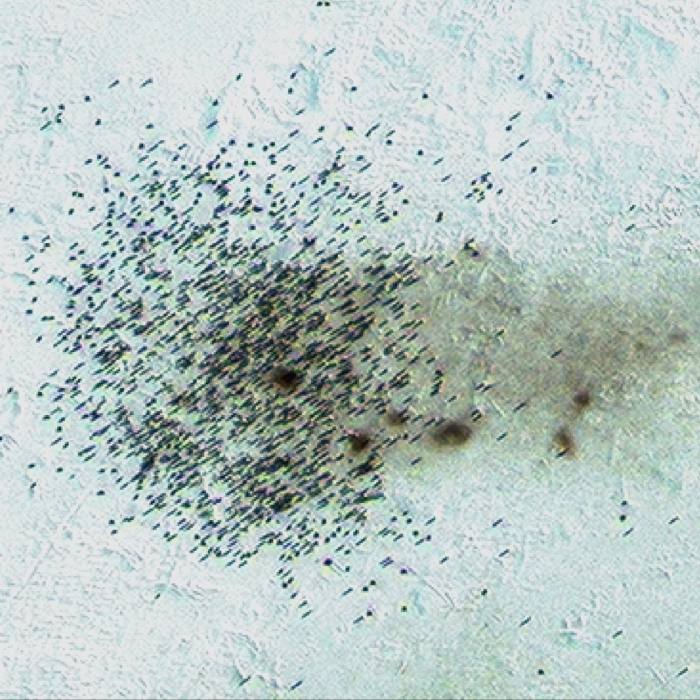

If the planetary picture is alarming for Fretwell, the emperor penguin’s plight seems personal. After all, the scientist is responsible for discovering half of their 60 known colonies, having pioneered the use of satellite imagery to locate them. “Penguins from space” is the title of his onboard lecture, which explains how he noticed dark smudges on the ice floes on satellite photographs and identified them as guano, the birds’ excrement. From penguin poo to penguins per pixel, the technique has enabled the mapping and tracking of the world’s isolated penguin population.

It’s an example of Fretwell’s philosophy of science — combining theory, technology and creativity. The latest satellites can identify individual penguins from 700km above the earth and reach the impossibly remote places where the birds live. But on-the-ground visits are vital. This trip is partly designed to help calibrate the satellite imagery, comparing remote photos with first-hand counts to offset the “shadow effect” when penguins huddle.

If that process is precise, Fretwell’s professional journey has been anything but. After leaving school he fell into a job managing a hardware store. Eleven years later, an experience with “a bad boss” led him to change careers.

“I still didn’t know what I wanted to do. One option was to become an artist, but I’d just got married and my wife was an artist, and we felt we can’t have two artists or we will never pay the mortgage. Or I could have been a mountain leader because I loved hiking and got some experience as a mountaineer. But I lived in Northamptonshire at the time and there were no mountains nearby.”

A longstanding interest in science won out and Fretwell returned to university to do a masters in geography. Failure to secure funding for a PhD, however, pointed to a dead end.

Fate intervened in the unlikely setting of a Northampton job centre. “In the first week I went there to sign on as unemployed, a job came up as temporary assistant map curator at the British Antarctic Survey,” he recalls — a title that seemed to revel in its lack of seniority. “It was the lowest grade you could possibly go in on, and I was basically making a loss because I was commuting 80 miles every day, there and back. But I loved the idea because when I was younger I’d read Shackleton and remembered those glorious stories of Antarctica.”

A talent for map drawing, the subsequent departure of a cartographer, Fretwell’s promotion and his innovations in mapping and satellite tracking, took him to the Antarctic’s penguin colonies and the world’s longest and most hazardous commute. The penguins can be grateful for such distant serendipity. But for a bad boss and a job centre visit, our understanding of their plight would not be as great.

An accidental hero for the penguins, perhaps, Fretwell is now focused on his mission. “Science has a big responsibility here in informing the public,” he says. “With emperor penguin science we haven’t really done enough because they are really, really hard to study. We have the most powerful non-nuclear icebreaker in the world and we still can’t get down to one of the penguin colonies we wanted to. We need more science, a clear message, and we need to up the ante.”

Plans are in train. Later this month, on Penguin Awareness Day, Fretwell and colleagues will unveil the discovery of a new colony, found by satellite, and will publish the first population trend on emperor penguins. This voyage itself will help get the message out, he believes.

The expedition was conceived and funded by Alex Ionescu, a technology expert and co-founder of CrowdStrike, a cyber security company. The exploration and research have been organised by Sedna, an international polar exploration consortium of scientists and academics. Their daily lectures range from the latest molecular data from the Southern Ocean to “The principles of planetary climate and the importance of the polar regions”.

In addition, the scientists are taking samples — including methane emissions, phytoplankton and rare earth minerals — to deepen understanding of this rapidly changing ecosystem.

“This is a very unique trip where we have 20 scientists on board and a mix of captains of industry, writers, artists, film directors, technology experts,” says Fretwell. “So the cruise itself is a conduit between the scientists and the people who can help make a difference. It really helps, because the scientific message needs to get out and scientists aren’t always the best communicators.”

And there is some positive news to communicate. The expedition has been to Snow Hill Island where, even though it was late in the breeding season, Fretwell found chicks that were fledging and viable. “So that colony seems to be doing all right and although the ice has broken up to a certain extent, these chicks are probably still going to be OK,” he says.

Far away from Snow Hill Island, though, powerful trends and political decisions will dictate the penguins’ fate. “We already have 30 years of warming in the atmosphere, even if we stop using carbon fuels now,” says Fretwell. “You could argue that without the treaties and agreements and the COPs, the rise in carbon emissions might have been exponential, but we are still on a linear trend upwards, which is really worrying.”

Is there enough urgency, I ask. “The clue is in the name,” he replies. “COP27. It’s the 27th time we have tried to address this,” he says, referring to the November climate change summit in Egypt. “It is just a matter of fact that politicians, from wherever they are, always fight for their own national cause. From a penguin perspective, though, there is no constituency. There are very few advocates for penguins because there is no population in Antarctica.”

Fretwell believes there is still time. “We must adapt and we can adapt as societies as to how we manage our resources. We need to change the narrative from the current theme of developed world versus the developing world and look at this as a global crisis.”

But the clock is ticking loudly. While Fretwell has recently found a new colony, he doesn’t foresee any more big discoveries, while existing communities are already suffering.

In the Bellingshausen Sea, on the other side of the Antarctic peninsula, four colonies had a total breeding failure last year. “A colony can occasionally have a bad year. But that is the first time we have ever seen a regional breeding failure with emperor penguins,” he says.

In layman’s terms, breeding failure means the grey fluffy chicks that tug at the heartstrings fall in the water and freeze or drown. It’s a depressing image that does little for our appetite for lunch, but much to underline the importance of Fretwell’s mission.

John Ridding is chief executive of the Financial Times Group

Details

John Ridding was a guest of Alex Ionescu. Le Commandant Charcot (ponant.com) is returning to the Weddell Sea for two voyages dedicated to studying emperor penguins in November; prices for the 12-night trip start at $26,870. For more on Peter Fretwell’s work, see bas.ac.uk

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter