Winning last month’s World Cup final cemented Lionel Messi’s place as the greatest footballer of his generation.

But the thrilling match, arguably the greatest final in history, was also a victory for host Qatar. Before Messi lifted the trophy for Argentina, Kylian Mbappé of France scored the first hat-trick in a final since 1966. Both play for Qatari-owned Paris Saint-Germain.

With the prestigious sporting event over, Qatar is seeking to keep momentum behind its push into sport, as the tiny desert state moves to diversify its economy away from oil and gas, further its soft power reach and burnish its credentials as investor.

One option now under consideration is an investment in the English Premier League. Qatar Sports Investments, the state-backed entity that bought PSG in 2011, recently held tentative talks with Tottenham Hotspur, according to a person familiar with the matter, although those at the London-based club denies it has discussed the sale of an equity stake.

QSI also has interests in padel — a niche racket sport mixing elements of squash and tennis — and in Formula One, through the Qatar Grand Prix. Plus, Qatar owns beIN, a dominant sports broadcaster in the Middle East and a big operator in Europe.

“Post-World Cup, there is a new strategy to really turbocharge that investment fund,” said a person familiar with the matter. “Being an ambitious sports fund with no interest in the Premier League is a bit of an anomaly.”

QSI has looked at English football before. In 2019, it held talks with Leeds United over a possible investment, when the club was in the Championship, the division below the Premier League, but failed to reach a deal.

Last year it decided to pursue a multi-club model, with investments in several football teams. The fund made its first move weeks before the World Cup, acquiring a 22 per cent stake for about €19mn in SC Braga, the team currently second in Portugal’s top division. QSI has also been looking at options in Belgium, Spain and Brazil.

It has simultaneously talked to US investors over a potential stake sale in PSG. Nasser Al-Khelaifi, QSI’s chair and president of the football club, told the Financial Times in November that he expected to achieve a valuation for PSG above €4bn in any future deal.

A move by the Qataris into the Premier League would mark a step up in ambitions. But they would almost certainly stick to a minority investment to avoid a conflict with their PSG ownership — Uefa, the governing body, bars clubs controlled by the same entity from competing against each other in European competitions.

It won’t be cheap, either. The sale of Chelsea FC last year to a group of US investors for £2.5bn raised the benchmark for football club valuations, meaning even a small investment in a top tier team could easily run into the hundreds of millions of pounds.

Qatar-watchers said the decision to target an investment in the Premier League, by far the richest and most watched league in football, was logical on a number of levels.

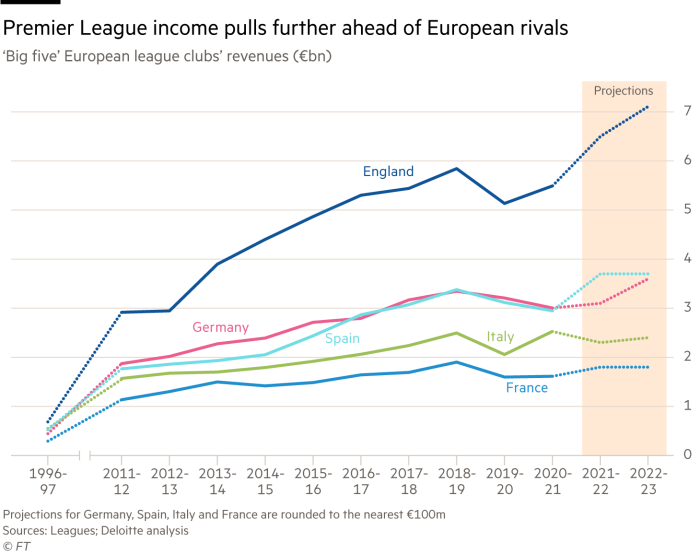

Financially, the league is light years ahead of the competition. Deloitte projects that revenue this year will top £6bn, boosted by big new TV deals in the US and Scandinavia. Meanwhile, the French league is expected to generate income of less than €2bn.

The Gulf has deepening ties in the Premier League. A member of Abu Dhabi’s royal family acquired Manchester City in 2008, before building out a network of clubs around the world. The team has gone on to win the Premier League six times since the takeover, although victory in the pan-European Champions League so far remains elusive.

Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund led a consortium that bought Newcastle United for about £300mn in 2021. Following more than £200mn of player purchases, the team is now third in the league.

“Sport is a key network to build economic influence,” said Paul Michael Brannagan, senior lecturer in sport management and policy at Manchester Metropolitan University. “These countries are all doing the same thing. If you’re Qatar, and you see that your closest regional neighbours both have Premier League teams — you’re not at the party, you’re on the sidelines.”

QSI’s current investment in PSG has been a success on the pitch — the team has won eight of the past 10 French titles although, like Manchester City, PSG has yet to win the Champions League.

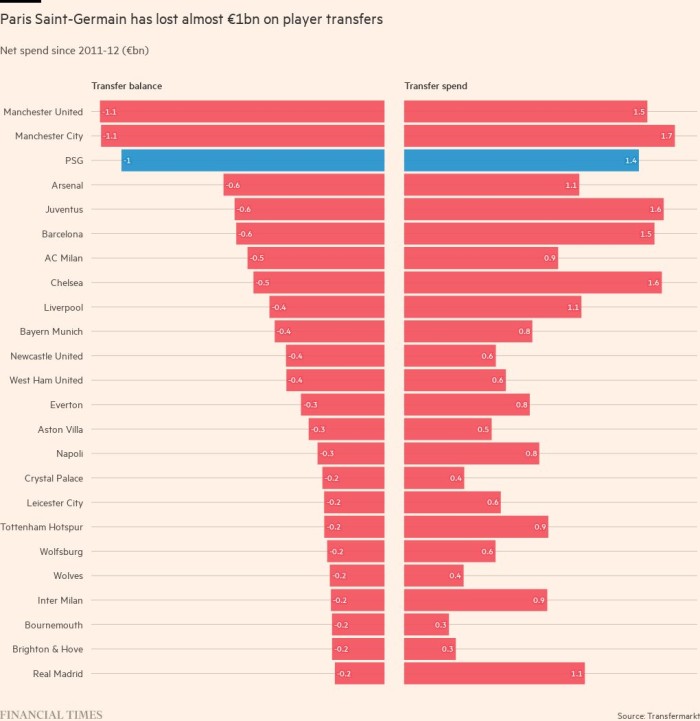

But the costs of the project have been high, especially in a league with the lowest income of Europe’s big five. In the past decade, PSG’s owners have spent €1.5bn on transfer fees, according to Transfermarkt, resulting in a net loss from player trading of €982mn. Only Manchester City and Manchester United have lost more from transfers in that time, while many of PSG’s French rivals have made profits from trading activity.

Those figures fail to take player wages into account. Following the arrival of Messi and a new contract for Mbappé, PSG’s wage bill soared 45 per cent to €708mn last season, according to Football Benchmark, a record in the sport. The increased spending pushed PSG to a post-tax loss of €369mn, in a year when elite rivals Manchester City and Real Madrid both recorded a profit.

As QSI weighs its options in English football, two factors are likely to influence any decision. As with Paris, location will be key. London is already a destination for Qatari investment — it owns luxury department store Harrods, the Shard skyscraper, and a 20 per cent stake in Heathrow airport — so buying into a team based in the city would “make sense”, said Brannagan.

With Abu Dhabi already involved in Manchester, and Saudi Arabia’s presence in England’s north-east, the UK capital remains an untapped football market for Middle Eastern money.

Qatar will also probably look for a team not currently challenging at the top of the table, as was the case when Manchester City, Newcastle and PSG attracted money from the Gulf. As such, investing in Manchester United or Liverpool — both of which are currently looking for new investors or potentially outright sales — appears unlikely.

“You don’t want to buy a successful team because how do you improve the performance?” said Brannagan. “You look at teams that aren’t used to winning trophies. You haven’t got anything to lose if you buy a club that doesn’t win anything.”