Indonesia’s bleeding toad (Leptophryne cruentata) is critically endangered.Credit: Pepew Fegley/Shutterstock

One-quarter of all plant and animal species are threatened with extinction owing to factors such as climate change and pollution. Starting this week, negotiators and ministers from more than 190 countries are meeting at a United Nations biodiversity summit called COP15 in Montreal, Canada, to address the emergency.

10 startling images of nature in crisis — and the struggle to save it

From 7 to 19 December, they will be trying to seal a new deal to save Earth’s biodiversity. The treaty, known as the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, is intended to establish precise targets for countries to protect and restore nature, including conserving 30% of the planet by 2030 and cutting nutrient pollution, such as reducing nitrogen fertilizer loss from farmland.

Time is running out. “We’re driving species to extinction at a rate about 1,000 times faster than they are created through evolution,” says Stuart Pimm, an ecologist at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, and head of Saving Nature, a non-profit conservation organization.

As COP15 kicks off, researchers and policy experts are concerned that countries still disagree on too many issues to secure a deal that will protect species and ecosystems effectively. Here, Nature looks at the extent of the crisis, and what scientists say countries must do to succeed.

Which species are most at risk, and what’s threatening them?

Among the most at-risk groups are amphibians and reef-forming corals. A global assessment shows that more than 40% of amphibians are threatened with extinction1, including the critically endangered bleeding toad (Leptophryne cruentata), which lives in Mount Gede Pangrango National Park in Java, Indonesia.

These toads were thought to be extinct until the year 2000, when some were spotted by a team led by Mirza Kusrini, a herpetologist at Bogor Agricultural University in Indonesia. But the researchers found that the amphibians were infected with chytrid (Chytridiomycota sp.), a fungus that has devastated global amphibian populations. Kusrini says that climate change is probably making life hard for the tiny toad, which got its common name from the crimson, splatter-like spots covering its body. Warm weather can stimulate fungal outbreaks and shift the timing of behaviours, such as the toads’ breeding season, making the amphibians vulnerable.

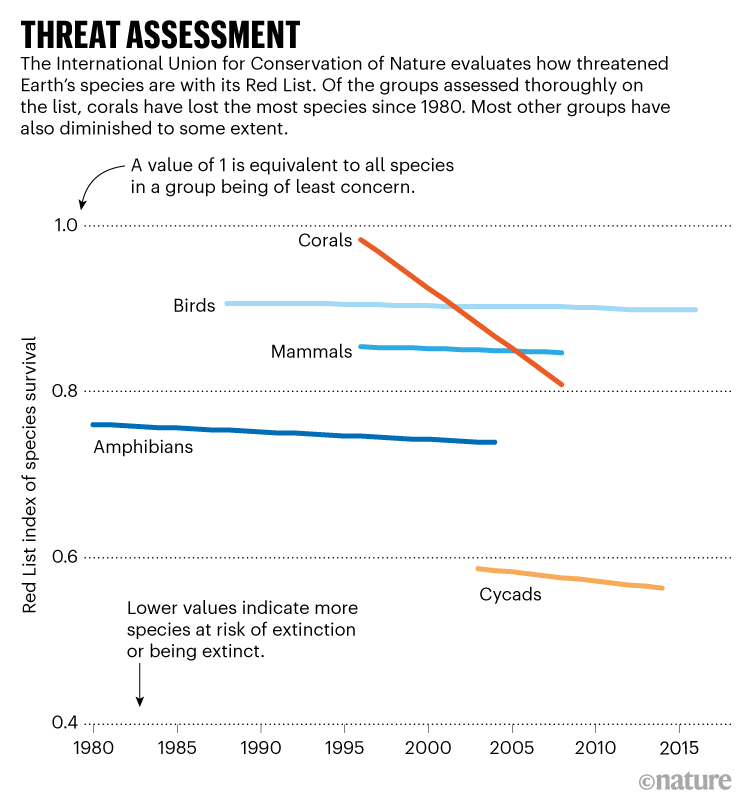

Source: Red List Index/IUCN

Global warming, which has been raising sea temperatures, is also responsible for harming coral reefs around the globe (see ‘Threat assessment’). Over a period of 9 years, up to 2018, 14% of the world’s coral died out — a massive problem, because today, coral reefs support one-quarter of all marine species.

Research shows that climate change is quickly becoming a large threat to biodiversity2. But still, the most-destructive forces are the conversion of land and seas for agricultural uses and people exploiting natural resources through fishing, logging, hunting and the wildlife trade. About 75% of land and 66% of ocean areas have been significantly altered, usually for producing food.

What might happen if species disappear?

It’s difficult to predict, because doing so requires knowledge of which species are present in a particular ecosystem, such as a rainforest, and what functions they have, says Shahid Naeem, an ecologist at Columbia University in New York City. Much of that information is often unknown. However, scientists have shown3 that ecosystems with less biodiversity are not as good at capturing and converting resources into biomass, such as happens when plants capture nutrients or sunlight used for growth.

Why deforestation and extinctions make pandemics more likely

Neither are less-diverse ecosystems as good at decomposing and recycling biological materials and nutrients. For example, studies show that dead organisms are broken down, and their nutrients recycled, more quickly when a high variety of plant litter covers the forest floor4. Ecosystems with low biodiversity also have low resilience — they are not as able to bounce back after a perturbation or shock, such as a fire, as more-diverse systems are, Naeem says.

“If we lose parts of our system, it simply won’t function very efficiently, and it won’t be very robust,” he adds. “The science behind that is rock solid.”

Ecosystems also provide clean water and can sometimes prevent diseases from spreading to humans. When species are lost, these services deteriorate, Kusrini says. For example, most amphibians eat insects, many of which are considered pests, such as cockroaches, termites and mosquitoes. Studies have shown a rise in cases of malaria — spread by mosquitoes — in areas in Central America where amphibian populations have collapsed5. “You know when they disappear”, Kusrini says, because insect numbers rise and people start using more pesticides to kill them.

What solutions do researchers say are needed to protect biodiversity?

Protecting and conserving habitats is central to saving species. This idea is captured in the framework being negotiated at COP15. The draft includes the goal of conserving at least 30% of the world’s land and sea by 2030. But for protections to be most effective, they must include regions that are rich in biodiversity, such as tropical forests, Pimm says. Despite an increase in protected areas worldwide over the past ten years, species numbers have still declined, because these safeguards were not in the right places, studies show6.

Delegates at COP15 in Montreal show their support for a new agreement among nations to protect Earth’s biodiversity.Credit: UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CC BY 2.0)

“What we’re going to be looking for at COP15 is more quality, not just more quantity,” Pimm says.

Eradicating invasive species is another important conservation strategy, and the framework’s draft currently calls for cutting the introduction of such species in half. Some estimates suggest that invasive predators, such as cats and rats, are responsible for more than half of all extinctions of birds, mammals and reptiles7.

It’s important that nations agree on a framework with at least some quantifiable targets, so that progress can be measured, and so that countries can be held accountable if they fail to meet their targets, researchers say. “I’m afraid what will happen is, they will produce a long list of ‘waffle’,” Pimm says. “We need quantification.”

Will nations manage to agree on a new deal to protect nature?

As COP15 begins, the outlook is not good. The text of the draft is still littered with unresolved issues. At a press conference on 6 December, Elizabeth Mrema, executive secretary of the Convention on Biological Diversity — the global treaty that underpins the new biodiversity deal — said that national negotiators had made insufficient progress in a final round of discussions before the start of the summit. She urged countries to compromise, otherwise they will fail to reach a deal. “The state of the planet is in crisis,” Mrema said. “This is our last chance to act.”

Troubled biodiversity plan gets billion-dollar funding boost

One key contentious issue is how to finance biodiversity conservation, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, which are home to much of the world’s biodiversity. These nations, including Brazil and Gabon, would like a new fund to be established with US$100 billion added per year in aid. So far, that proposal has not gained traction with wealthier countries. “They really need to have the financial commitments, because things don’t get done without the money,” Naeem says.

Despite the pessimism, Naeem is certain that scientists and advocates will keep pushing for a deal. “There would be real change” if countries were able to achieve a universal decrease in biodiversity loss, he says.