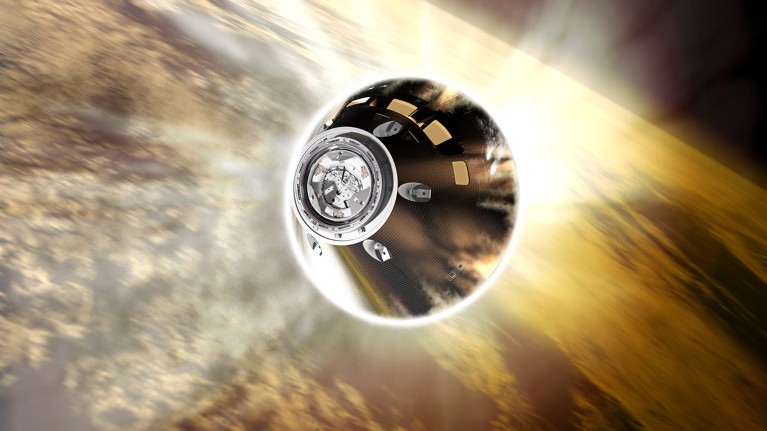

The heat shield on NASA’s Orion capsule will endure temperatures around 2,800 °C during re-entry, as depicted in this artist rendering.Credit: NASA

Over the past three weeks, NASA’s Orion capsule has flown to the Moon and most of the way back, in a near-flawless test of a new spaceship. It now faces its biggest challenge since launching atop a massive rocket as part of the Artemis I mission — surviving a fiery re-entry through Earth’s atmosphere and splashing down in the Pacific Ocean on 11 December. In the process, it will test a re-entry manoeuvre that has never been used by a passenger spacecraft.

NASA’s Orion spacecraft reaches the Moon — in pictures

The capsule isn’t carrying any astronauts. But one day, it’s supposed to. NASA needs to get Orion home safely to keep on track with its Artemis programme, which aims to eventually return humans to the Moon’s surface.

For re-entry to go just right, the capsule will need to slow down from around 40,000 kilometres per hour when it hits the top of Earth’s atmosphere, to just 32 kilometres per hour when it drops into the Pacific. The brunt of that braking energy will be borne by Orion’s heat shield, which will endure temperatures of around 2,800 °C — hotter than what’s needed to make steel.

All eyes will be on the heat shield, constructed from the same epoxy resin that was used during the Apollo programme in the late 1960s and 1970s, but which has now been applied in a different fashion to Orion. “We are looking forward to [re-entry] tremendously,” says Debbie Korth, the deputy programme manager for Orion at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.

Record setter

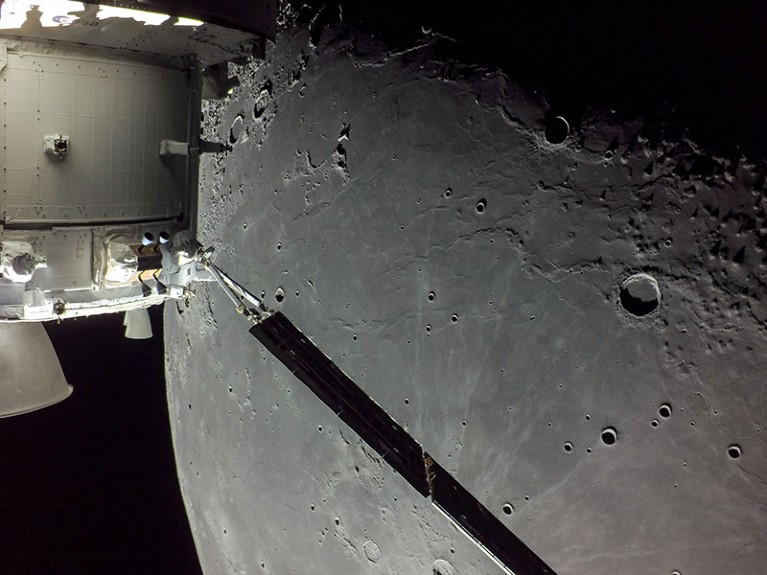

Artemis I launched on 16 November, sending Orion whizzing past the Moon six days later. On 25 November, the capsule fired its engines to enter a high-altitude lunar orbit, which set a distance record — 432,210 kilometres — for the farthest that a capsule designed to carry humans and to return to Earth has travelled from the planet’s surface. By the time it splashes down, Orion will have travelled more than 2.2 million kilometres.

During Orion’s second Moon flyby, it snapped this image of the far side of the lunar surface, on 5 December.Credit: NASA/JSC

Mission controllers have encountered some minor glitches during the flight, including a problem with power flow between two parts of the spacecraft. But most of the journey has gone remarkably well.

Orion’s interior — where four astronauts will sit the next time it flies, on the Artemis II mission — is currently staffed by one mannequin and a floating Snoopy doll. NASA is not testing any life-support systems on this flight, so temperatures in the crew cabin are a bit chilly, around 10–12 °C.

What is being tested are the effects of space radiation on simulated humans. The capsule holds two faux human torsos; one of them is strapped into a vest to protect it against radiation, and the other is not. Detectors on the torsos measure radiation dosage as Orion flies out of and back into Earth’s magnetic shield, which protects our planet against harmful solar energy. Other experiments inside Orion are measuring the effects of radiation on organisms including yeast. None of these data can be collected and studied until after splashdown.

Hop, skip and a jump home

Orion is on a precisely engineered path to return to Earth off the coast of San Diego, California, at 9:40 a.m. local time on its designated return date. “We’re targeting for a very thin slice of atmosphere,” said Nujoud Fahoum Merancy, NASA’s chief of exploration mission planning, during an agency broadcast on 5 December.

Engineers have extensively tested the systems that will help upright Orion when it splashes down on 11 December. (The test shown here was performed in the Atlantic Ocean in 2019.)Credit: NASA

Like a stone skipping across the surface of a pond, the capsule will hit the atmosphere around 122 kilometres above Earth’s surface, then plunge to around 61 kilometres before deliberately skipping higher, to just under 91 kilometres, before descending again. This unique ‘skip’ entry, which has never before been used to return a passenger spacecraft to Earth, will allow Orion to adjust the distance it travels while re-entering, and thus to pinpoint its landing more precisely. This could help the capsule land closer to a US navy ship stationed nearby in the water to recover it.

Lift off! Artemis Moon rocket launch kicks off new era of human exploration

During re-entry, much of Orion’s energy will be imparted to Earth’s atmosphere, causing the pressure and temperature in the air flowing around the vehicle to spike. The air will get so hot that nitrogen and oxygen molecules in the atmosphere will break apart, causing a flow of ionization around Orion that will block communications for several minutes. “That will be the most nerve-wracking part of the mission for me,” says Joe Bomba, an engineer at Lockheed Martin in Littleton, Colorado, who worked on developing Orion’s heat shield.

The capsule will jettison part of its cover around 7 kilometres above Earth’s surface and then deploy 11 parachutes in rapid sequence, to slow the capsule for splashdown. Recovery teams on the waiting ship will then pull the capsule on board its hangar-like ‘well deck’.

Only then will Bomba breathe a sigh of relief. “Being an engineer,” he says, “I’m not going to sleep well until we’re in the well deck.”