Originally published October 2011; updated December 2022.

It’s one of the first eye-openers for people who are just starting to pick up birdwatching: the experience of hearing a birder call out names of birds in quick succession as a flock passes by, seemingly without looking. But like anything, it’s mainly practice—and it’s surprisingly easy to learn. You can watch (and listen to) birds pretty much anytime you’re outside. You mainly just need patience, careful observation, and a willingness to let the wonder and beauty of the natural world overtake you. Here are some tips on how to get started:

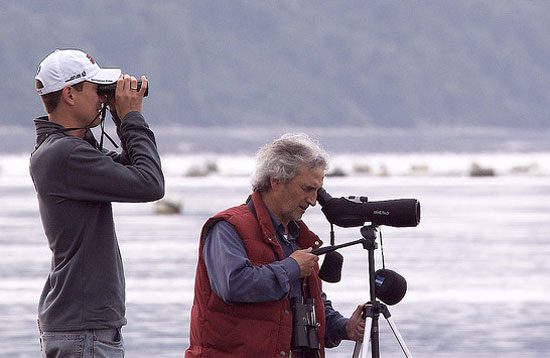

1. Binoculars. Your enjoyment of birds depends hugely on how great they look through your binoculars, so make sure you’re getting a big, bright, crisp picture through yours. In recent years excellent binoculars have become available at surprisingly low prices. So while binoculars under $100 may seem tempting, it’s truly worth it to spend $200 to $300 for vastly superior images as well as better warranties, waterproof housing, and a great feel.

Great models for beginning birders include the Opticron Oregon, Celestron Nature DX ED, and Hawke Nature-Trek 8×42. (More reviews of binoculars here.) In general, 8-power binoculars are a nice mix of magnification while still allowing you a wide enough view that your bird won’t be constantly hopping out of your image. Here’s more advice about buying optics without breaking the bank.

2. Field Guide. Once you start seeing birds, you’ll start wondering what they are. An informal poll of my coworkers showed a clear field guide favorite: the Sibley Guide, in either its full North America version or smaller, more portable Eastern and Western editions. Other useful guides are Kaufman’s, Peterson’s, and the National Geographic guide. Don’t forget that on the Web you can get information and sounds for more than 600 species for free on our All About Birds site or on your phone with the free Merlin Bird ID app.

3. Bird Feeders. With binoculars for viewing and a guide to help you figure out what’s what, the next step is to bring the birds into your backyard, where you can get a good look at them. Bird feeders come in all types: we recommend starting with a black-oil sunflower feeder. Add a suet feeder in winter and a hummingbird feeder in summer (or all year in parts of the continent). From there you can diversify to millet, thistle seeds, mealworms, and fruit to attract other types of species. Our Feeding Birds section is a great place to learn about this.

4. Spotting scope. By this point in our list, you’ve got pretty much all the gear you need to be a birder… until you start looking at those ducks on the far side of the pond, or shorebirds in mudflats, or that Golden Eagle perched on a tree limb a quarter-mile away. Though they’re not cheap, spotting scopes are indispensable for getting those last few clues about a species ID—or to simply revel in intricate plumage details that can be brought to life only with a 20x to 60x zoom. And scopes, like binoculars, are coming down in price while going up in quality.

5. Camera. With the proliferation of digital gadgetry, you can take photos anywhere, anytime. Snapping even a blurry photo of a bird can help you or others clinch its ID. And birds are innately artistic creatures—more and more amateur photographers are connecting with birds through taking gorgeous pictures. There’s also the popular pursuit of digiscoping—pointing your camera through a spotting scope or binoculars.

6. Skills. Once you’re outside and surrounded by birds, we recommend practicing a four-step approach to identification. First you judge the bird’s size and shape; then look for its main color pattern; take note of its behavior; and factor in what habitat it’s in. We’ve got free online tutorials to let you practice each of these skills, and a free Inside Birding video series that walks you through each one.

7. Records. Birders like the ones who inspired the 2011 movie The Big Year are called listers—people who love (or are obsessed with) compiling lists of the species they’ve seen. But you don’t have to be a lister to reap benefits of writing down what you see—think of notes as a kind of diary with a focus, chronicling the days of your life through the birds you’ve seen and places you’ve been. Many people keep their records online in our free eBird project, which keeps track of every place and day you go bird watching, allows you to enter notes and share sightings with friends, and explore the data all eBirders have entered.

8. Apps. If you have a smartphone, you can carry a bookshelf in your pocket. Most of the field guides mentioned above are available as apps, and most of them add in sounds you can listen to as well. Merlin Bird ID can help you ID more than 7,500 species across the planet; and eBird Mobile can keep track of your checklists and help you find your way to birds you want to see. And our All About Birds species guide also works on mobile devices, giving you access to free ID information and sound recordings straight from your phone’s Internet browser.

9. Connections. Birdwatching can be a relaxing solo pursuit—a walk in the woods decorated with bird sightings. But birding is also a social endeavor, and the best way to learn is from other people. Get connected with your local birding club—there’s a decent chance that someone’s leading a bird walk near you this weekend—and they’d love to have you come along.

What did we miss? Drop us a note in comments to let us know your own must-have equipment for bird watching.