In the 1980s, a group of community leaders from around metro Detroit began gathering regularly to talk about building community coalitions. At the invitation of New Detroit, they formed a racial justice organization in response to the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. Leaders gathered to broaden the participation of communities of color and act together in difficult times or when there were social problems.

Roughly 30 leaders met monthly, including representatives from the African and African American, Arab, Caribbean, Chinese, and Latino communities. At each meeting, a participating ethnic group presented their community and gave an update on art, culture, and the different socioeconomic issues afflicting them.

“We talked about everything,” says Marshalle Montgomery Favors, program manager at New Detroit. “We talked about surveillance of the community in Southwest Detroit, and the presence of law enforcement … We talked about deep issues that concerned the community such as immigration and issues related to businesses, and the hiring practices in the community.”

After each presentation, they socialized and built relationships by sharing food from the presenting community.

“We wanted to get to know each other beyond a surface level,” Montgomery Favors says. “We were intentional about bringing people together. Diversity doesn’t happen as organically as people would like to think.”

By the early 1990s, Detroit had suffered from decades of white flight and financial disinvestment at the state level. The rapid population decline left the city littered with abandoned buildings, and high levels of unemployment led to widespread poverty and crime.

“We were intentional about bringing people together. Diversity doesn’t happen as organically as people would like to think.”

tweet this

The relationship between Detroit and the mostly white suburbs was fraught with racial tension. This friction was exacerbated in 1992 by the killing of Malice Green, an unarmed Black man, at the hands of white police officers. The incident gripped the Black community and left Detroiters reeling. News of his death spread quickly and the incident became a national story that dominated news cycles for weeks.

With tension permeating the city, building a network of communities of color was imperative. As a result, the participating leaders formed the Cultural Exchange Network, focusing on building individual and personal relationships with other leaders, and going to one another’s cultural events.

“We felt the need to gain more power and gain awareness about the communities, and we knew that united together, we could have more impact,” says Osvaldo Rivera, member of the Cultural Exchange Network.

At that time, Detroit’s demographics were radically changing. Between 1980 and 1990, Detroit had become a majority Black city, and the surrounding suburbs were experiencing immigrant population growth. Thousands of people were migrating from the Middle East as well as India and Albania.

“In Southeast Michigan, immigrant communities have tended to be in enclaves on their own, both due to a history of racism and also the ability for new immigrants to be able to find affordable housing,” says Ismael Ahmed, director of the Concert of Colors.

According to Ahmed, as the immigrant populations grew, there was very little interaction between those communities, and at times the intra-community relationships were hostile. Issues often arose between Arab gas station owners in Detroit and the Black customers they served. The lack of social connection, the largely transactional nature of gas stations, and racist attitudes toward Black people led to racial tension.

“Yet there was no uprising or anything around Black Detroiters, and the Arab-owned gas stations. And the reason there wasn’t was because of the work being done behind the scenes,” says Shirley Stancato, member of the Board of Governors at Wayne State University and the former president of New Detroit.

“You would be amazed at the things that didn’t happen because we were working together behind the scenes and having deep conversations,” Stancato says. “That’s the kind of work that helps build community and develops relationships. You sustain those relationships through the tough times, and that’s a big, big piece of the concept around the Concert of Colors.”

The Concert of Colors at Chene Park

After years of the Cultural Exchange Committee working together to unify communities, an opportunity arose to advance their work and celebrate cultures through music. New Detroit and community leaders saw a cultural event as a means to take the work of the multi-racial coalition-building of the Cultural Exchange Network and create a cultural experience that would promote activism and connect communities through music, art, and food.

In the early 1980s, Mayor Coleman A. Young envisioned an amphitheater along the Detroit Riverfront near downtown — one that would rival other venues and redevelop the city’s long-neglected waterfront. From land historically used for industrial purposes, the city built Chene Park (now known as the Aretha Franklin Amphitheatre). Ron Alpern, the Riverfront Parks Program Coordinator at Detroit Recreation Department, offered the amphitheater to ethnic organizations, including the Cultural Exchange Network, to promote diversity.

With a long history of organizing live events and managing bands, Ismael Ahmed, still the president of the Cultural Exchange Network, had the expertise to produce just such an event. Ahmed tapped into the leadership of the Cultural Exchange Network to help create a line-up of musicians that represented the various cultures and ethnicities of metro Detroit to promote world music.

Cultural impact

Thirteen years after the first concert, communities and musicians across metro Detroit could feel the impact of the Concert of Colors. The free live music event brought together Black, white, ethnic, and immigrant communities from across the region, creating a deep sense of community and well-being that no other festival or music event in Michigan had.

“The Concert of Colors was the only festival whose guiding principle was diversity, where you could hear music and be able to meet people from all over the world. It was pretty amazing,” says Phil Clark, 72, a lifelong Detroit resident who attended the event yearly.

Organizers of the Concert of Colors understood that music brings people together in powerful ways and could improve people’s unconscious attitudes toward other cultural groups, and that was the point. In addition, live music carried out a range of psychological and social functions shaping people’s emotions and behaviors toward one another.

“One of the things that the Concert of Colors tapped into is this understanding that music is one of the most effectively unifying cultural experiences that people can have,” says Detroiter Ofelia Saenz. “That it’s a conduit for understanding and bringing people together.”

With tension permeating the city, building a network of communities of color was imperative.

tweet this

In addition to the rich diversity on stage and off, one of the main components of the Concert of Colors’ success was that it was intentionally inviting to families. Having children at an event deepened a sense of community. And for a city with high unemployment and stagnant wages, it shouldn’t be lost that COC is one of the few events a family could bring their kids to for free.

“The concert was a family affair because you take your kids there. And there was such a sense of family that was created because people would go every year and ask, ‘What about your cousin? What about your daughter? I remember when your kids were eight years old, and now they’re in their early thirties,’” says Rivera, who in addition to being a founding member of the Cultural Exchange Network, is also a Latino community leader in Detroit.

For Detroiter and concert-goer Karla Robinson, the concert brought out the “humanity and goodness of the people” who attended.

“I would sit on the grassy mound behind the seats where all the moms hung out. Our kids played together, and we shared snacks and water,” she says. “When you have kids, you are always on guard, and at the Concert of Colors, I could actually relax and enjoy the music because I knew the other moms were watching my kids just like I watched out for theirs. You can’t get that feeling anywhere.”

Leaving Chene Park

In 2006, the Concert Of Colors was dealt several devastating blows. The partnership with Chene Park and the City of Detroit ended leaving the future of the Concert of Colors uncertain.

“The amount of money we were being asked to pay each year continued to grow until we couldn’t pay it. Chene Park was over $100,000 dollars for the three days, just for the security, set up, and venue,” Ahmed says. “The last couple of times, the head of the Detroit’s recreation department got on the phone with me and started calling funders and corporations to try to raise the difference, but it just became too difficult.”

During that same period, Detroit began creeping into the Great Recession. The downturn devastated Detroit’s already fragile economy and would last longer than in any other major city in America. As a result, all sponsors lowered their giving amount, and Concert of Colors’ main corporate sponsor, Daimler Chrysler, stopped giving their yearly contribution of $300,000.

“There was disinvestment from both corporate and from foundations, and the Concert of Colors had less to work with,” Ahmed says. “That same year, New Detroit, who was putting in $100,000, said they could no longer afford to do it.”

Committed to the festival’s long-term success, organizers decided that instead of ending the festival they would find a way to continue.

“They were all very, very different, with different cultures, gorgeous cultures, beautiful cultures that could be shared,” Ahmed says. “The Concert of Colors is unique, it relies on communities of color and presents music and art that nobody else presents. I fell in love with it — there’s nothing like it, not only in Detroit but pretty much countrywide. It would be a terrible loss to walk away from it.”

New performance location and new partnerships

In late 2005, with New Detroit no longer the host organization, no venue, and little money, COC organizers had to restructure the festival and find a way to continue.

The first thing Ahmed did was find a new host organization where the year-long process of producing the festival could take place.

“I brought it into ACCESS, where we could do it with our own staff. I was the director of ACCESS then,” Ahmed says.

With a host organization in place, Ahmed began to approach music and concert venues, including the Detroit Symphony Orchestra (DSO), where he met the newly appointed president, Anne Parsons. It was very early on in Parsons’s tenure at the DSO.

Concert of Colors finances

1993: Concert of Colors organizers started with a budget of $100,000.

1997: COC budget had grown to $700,000.

2002: Ten years after the first concert, organizers ended the decade with a budget of $1.2 million.

2006: COC’s operating budget shrinks to $350,000 and continued to decrease.

One afternoon, Kendra Whitlock, the manager in charge of partnerships and programming, approached Parsons with an idea. “We’ve had this amazing world-music festival on the riverfront for years and they’re facing challenges,” Parsons recalls. “And they’re not sure they can continue on the riverfront. And they’re looking for a venue.”

At the time Parson and her team were looking to create viable, sustainable partnerships with communities that fit with the mission of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra.

Parsons agreed to meet with Ahmed. “During our meeting, I did a lot of listening to Ismael,” Parsons says. “And without hesitation I said, ‘We would love to be your partner.’”

In the early 2000s, the Midtown district had multiple performing arts venues but few other attractions. After 5 p.m., the area was desolate. Suburbanites attending concerts came and immediately got on the freeway and went back home when the concert or event was over.

“I was so excited by the idea that we could activate Midtown through our building and through a partnership with someone like Ismael and with a festival that was already established,” Parsons says. “It was an enormous opportunity for us because we were trying to change the perception of the role of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra in the community.”

Parsons, like Ahmed, understood the power of music. The Concert of Colors not only boosted cultural pride, but had a positive social, and economic impact on the community.

“Music was the language that everyone could speak,” Parsons says. “It was a connector. It brought people together and it promoted understanding.”

The partnership meant a significant financial commitment on behalf of the DSO.

“I think our costs were something like $75,000 for the weekend, and so stagehand labor was a big part of that,” Parsons says. “There was a way of cutting the cost down, and so we just kept whittling away at that …. trying to figure out how to make it manageable.”

One of the challenges facing organizers was changing the location to DSO’s Max M. Fisher Music Center. For more than 15 years, the Concert of Colors played at Chene Park, an outdoor venue with sweeping views of the Detroit River, and a lawn where people could sit, which created a mid-summer cultural experience.

Would having an indoor concert lose the intimacy it had at Chene Park? Would people be too disappointed that they were not outdoors or near the Detroit River?

While some were dissatisfied with the new location, most followed the music to Midtown. “The first year we were pretty happy with the turnout,” Parsons says. “We never had to turn people away, we had a constant stream of people coming and going the whole time.”

Midtown

In 2011, three years after the official start of the Great Recession, Detroit still suffered from a crippling housing crisis and a 12% unemployment rate, double the national average. Concert of Colors organizers still struggled to raise money and many said they should charge an entry fee to offset the cost. But keeping the concert free was imperative for organizers.

“Everybody should be able to enjoy each other’s culture and music and art, and even small fees tend to undermine that,” Ahmed says.

The alliance with the DSO ushered in a new era for the Concert of Colors and served as a conduit to other partnerships. Ahmed approached other venues in the area and formed collaborations with the Detroit Institute of Arts, Charles H. Wright Museum of African History, and the Scarab Club. By 2011, six years after they changed locations, COC had grown into a two-day event.

“We didn’t have a lot of money, but we had a lot of friends,” Ahmed says.

The Concert of Colors was a regional attraction, and because of the new partnerships, COC now had a larger geographic footprint, which allowed attendees to walk from venue to venue, enjoying live music from around the world, exposing many suburban visitors to respected cultural institutions for the very first time.

“We didn’t have a lot of money, but we had a lot of friends.”

tweet this

“It was an honor to be asked to be involved with the Concert of Colors,” says Larry Baranski, director of public programming at the Detroit Institute of Arts. “It was an experience of joy that was designed for everyone. It resonated is the thing, there are a lot of concepts that are tried and they just don’t resonate, ‘Concert of Colors was something that worked almost immediately.’”

Midtown Inc. also came on as a partner and threw its weight behind the event, adding New Center Park to the list of venues. Sue Mosey, executive director of Midtown Detroit, Inc., understood the Concert of Colors was an important addition to Midtown’s cultural landscape.

“People often overlook that festivals can be vehicles for forming communities and shaping the identity of a city,” says Mosey. “In this case, music is the global language that brings all types of people together to experience joy, happiness, and fun.”

Don Was All-Star Revue and Detroit’s music scene

The live music performed at the Concert of Colors exposed generations of metro Detroiters to music they would have otherwise never heard, and in the process infused an already musical city with beats from around the globe.

“I was lucky enough to hear everybody from Ray Charles to King Sunny Adé and groups that I would not ever have heard of if it weren’t for the Concert of Colors” says Phil Clark, who lives in Southwest Detroit. “I saw the Paris Combo and I still listen to them.”

Famed Arab musician Cheb Khaled performed on the main stage in 2005. Playing bass with Khaled that year was musician Don Was, a legend in the music industry, and one of the most sought-after producers in contemporary music. Was has worked with the Rolling Stones for 30 years, and produced albums for Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson, Bob Seger, Alison Kraus, and dozens of others.

Was says the mid-summer cultural experience of the Concert of Colors left an indelible mark on him.

“I was just blown away. It felt like home, you know, and I really felt that community. There was just a feel to it that was not only familiar, I think it’s unique to Detroit. There is a unique kind of cultural jambalaya going on here as a result of the auto business and it was just the best of it,” Was says. “To see every kind of person hanging out, eating different foods and getting along and just having the beautiful day sitting in the grass and hearing music, and I was really taken by it.”

During that visit, Don Was formed an enduring friendship with Concert of Colors organizer, Ismael Ahmed.

“I met Ismael that night. We had dinner after we played. And then I learned his history of activism, we had a whole lot in common politically and musically,” Was says. “We bonded over a love of the MC5, and union organizing and that kind of thing. And we just became really good friends from that.”

A few years later, Was says he was thinking back on his experience at Concert of Colors and reached out to Ahmed with an idea of producing a show that displayed Detroit’s rich musical talent.

“I’m president of this record label, Blue Note Records, which is arguably the most formidable jazz label in history. All the greats, from Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk and Sonny Rollins, through Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter … there’s an inordinate number of Detroit musicians featured on these albums throughout history, it’s staggering,” Was says. “There’s something very special about Detroit, and Detroit’s music to me.”

Orchestra Hall, the stunning Beaux-Arts building with world-class acoustics and home of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, became the perfect location for what would be an amalgamation of Detroit musicians from various genres of music coming together under the direction of Don Was to perform a free concert for the people of the city.

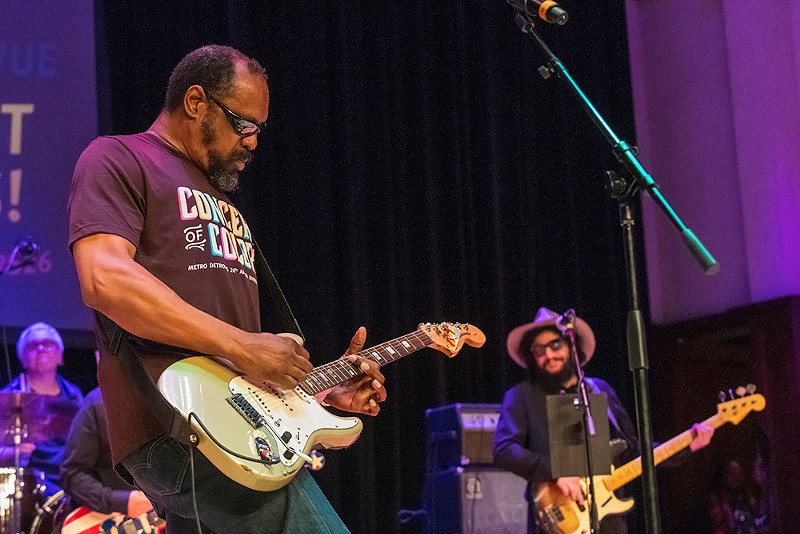

Christened the Don Was Detroit All-Star Revue, Was and the band played music made in Detroit— an homage to the city’s music heritage, and paid tribute to Detroit luminaries such as John Lee Hooker, George Clinton, and Bob Seger. The concert became an instant hit. And every year since, people flock to Orchestra Hall often waiting in long lines to get a seat, to hear incredible music made in Detroit by the city’s most talented musicians.

Yet, as much as the crowds enjoy the concert, the experience is equally unforgettable for the musicians.

“It’s a great honor,” says Laura Rain, lead singer for Laura Rain and the Caesars. “The high caliber of musicianship with Don Was, a rockstar, and all the cats on the stage, you want to bring your best and show everybody that you’re there to play the music. We are always in awe when we get asked to come back.”

For Oscar-winning composer Luis Resto, it’s about the music community. “That moment you’re performing, it’s wonderful, to be able to be with colleagues on stage for that moment in a song, you know, the unification and the communication that happens, sometimes without words and the energy and the support and love that comes through people playing together.”

Resto says being chosen to perform with Don Was is an affirmation “that musicians are able to have this moment because of what they’re doing. That it impacted someone’s ears to guide them to this moment. And it happens to be with Don Was. And I think that in itself gives them a real impetus to dig in and move forward in whatever path they’ve been doing.”

Don Was Detroit All-Star Revue has performed for 15 years as part of the Concert of Colors, a highlight in a free music festival that brings all cultures together.

“It’s like a family reunion,” Was says. “I’m gonna do it ‘till I drop.”

The 30th Anniversary of the Concert of Colors will be held from Saturday, July 16-Sunday, July 24 at various venues across metro Detroit. This year’s lineup features Ukrainian folk quartet Dakhabrakha, Alejandro Escovedo, Martha Redbone, the Burnt Sugar Arkestra with Vernon Reid of Living Colour, and the Don Was Detroit All-Star Revue Tribute to Iggy Pop & the Stooges. See concertofcolors.com for the full schedule.

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, or TikTok.