Editor’s note: Grist is hosting a free virtual event on January 9, 2025, at 2 p.m. EST / 11 a.m. PST to analyze the progress and challenges seen at the U.N. climate conference known as COP29. Join Grist’s Jake Bittle in conversation with attendees and experts about where global climate negotiations go from here. Register here.

The essence of the Paris climate agreement was distilled into a single number. The almost 200 countries that signed the pact in 2016 agreed they would try to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Over the past decade, as these countries have rolled out renewable energy installations and decommissioned coal plants, we have been able to evaluate their efforts against this number. (The results have not been promising.)

But the 1.5-degree target was just one element of the Paris accord. The world also committed to throw its weight behind efforts to adapt to the global warming already baked in by centuries of fossil-fueled industrialization. Even if emissions fall, disasters over the next century will displace many millions of people and destroy billions of dollars in property, particularly in developing countries across Africa, Latin America, and Asia. Those countries fought to ensure that adaptation to those hazards was a key pillar of the agreement.

But there’s no one way to measure the success of this commitment. Should the U.N. measure the number of deaths from disasters, or the value of property destroyed in floods, or the incidence of hunger, or the availability of clean water? How will the international community determine the efficacy of adaptation measures like sea walls and drought-resistant crops, given that the disasters they prevent remain so unpredictable?

“There is no one single measure you can use that will apply to all adaptation globally,’” said Emilie Beauchamp, an adaptation expert at the International Institute for Sustainable Development, a think tank, who is participating in adaptation talks at COP29, this year’s U.N. climate conference in Baku, Azerbaijan. “It’s not like when we say, ‘we reduce our emissions.’ You can say we need to reduce vulnerability, but that’s going to change according to whose vulnerability you’re talking about.”

This question is far from academic: Climate change is fueling more frequent and severe disasters, ravaging places with vulnerable infrastructure. In Zambia, electricity service has been reduced to just a few hours a day thanks to drought emptying out a key reservoir. Meanwhile, a year’s worth of rainfall deluged the Valencia region of Spain in just a few days last month, causing flooding that killed more than 200 people. In the United States, warming helped juice the intensity of several major hurricanes that made landfall this year.

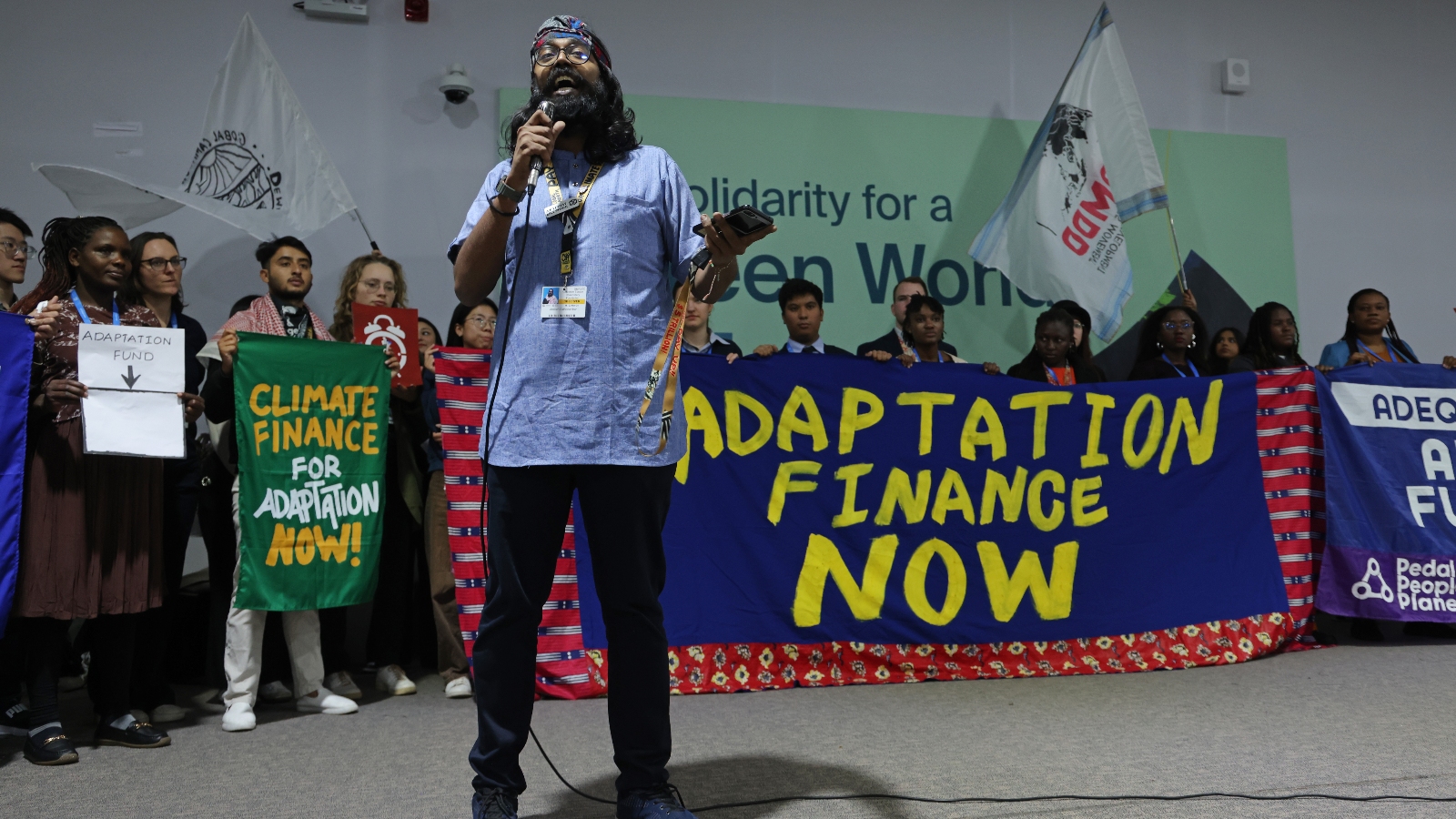

Despite the urgency, adaptation hasn’t received much attention at recent U.N. climate talks. This year’s COP is no exception. While the conferences often open with rich countries making major new funding pledges, this year just $60 million in new pledges went to the world’s biggest adaptation fund. That total, raised by European nations and South Korea, is well short of the $300 million the fund had hoped to raise.

While the main target of COP29 is a new agreement on a global finance goal — which could end up well over a trillion U.S. dollars and is intended to help the developing world with all aspects of the climate fight — wealthy countries have refused to reserve a portion of that target for adaptation, in part because adaptation efforts attract far less private investment than renewable energy. In finance talks, developing nations have asked that billions of dollars be set aside for adaptation — a far cry from the $60 million announced at the start of the conference.

Despite the funding impasse, the world is inching closer to finally defining an effort that could make the difference between life and death for millions of people around the world. The U.N. is halfway through a two-year attempt to finally pick “adaptation indicators,” or global yardsticks that will allow every country to measure its climate resilience. This decade-delayed effort to complete the ambitions of the Paris Agreement will in theory give the world a way to measure adaptation success.

“We’re hopeful,” said Hawwa Nabaaha Nashid, an official at the environmental ministry of the Maldives, an island state in the Indian Ocean. “If there’s a high-quality [outcome], we can answer the question—how well are we adapting and what needs to be done differently?”

There are still big hurdles to clear. The latest text of the adaptation negotiators were considering, which appeared early Thursday, left out some priorities of developing countries, but negotiators expressed more optimism about the adaptation item than they did about other items such as decarbonization and climate finance.

And the task of selecting indicators is daunting in itself. Last year’s COP saw agreement on specific target areas for adaptation, including water, health, biodiversity, food, infrastructure, poverty, and heritage. But to measure progress in these target areas, negotiators have proposed a whopping 10,000 potential indicators. This eye-popping sum highlights just how fluid and context-dependent the notion of “ climate adaptation” really is.

Some potential indicators, like “area of contorta pine” (a European Union proposal on biodiversity) and “number of boreholes drilled” (a water proposal from developing countries) seem far too specific, since most of the world doesn’t have significant amounts of contorta pine or get its water by drilling boreholes. Others, such as “types of synergies created” seem so vague as to be almost useless. Some, such as “number of mining operations in protected areas reviewed and temporarily suspended” don’t seem to have anything to do with adapting to climate disasters.

“By the very nature of adaptation being more diffuse and broad, you get a multitude of indicators, sub-indicators, and criteria,” said Kalim Shah, a professor of environmental science at the University of Delaware who has assisted small island states like the Marshall Islands with adaptation planning. “It’s much more diffuse, and maybe that’s part of the problem: too many cooks in the kitchen.”

The major roadblock in these discussions is money. In every negotiation, poor countries have demanded clear language acknowledging that adaptation is impossible without adequate funding, while rich countries have tried to exclude such language and focus on planning and logistics. In the fight over the indicators, the developing world is seeking a commitment to include an indicator that measures “means of implementation” — in other words, a metric for how capable countries are of carrying out their adaptation plans. This would amount to an acknowledgement that funding and capacity are critical to climate adaptation of any kind, whether it’s building new sand dams for pastoral herders or tracking the spread of dengue fever. But even that acknowledgement appears to be controversial.

“It is still a big contention,” said Portia Adade Williams, who is negotiating adaptation needs on behalf of Ghana. “I’m still not sure how we are going to end it. But from a developing country point of view, this would be a complete red line, to have a decision that doesn’t allow us to track [capacity].”

Nashid, of the Maldives, said the country can’t consider scaling up its adaptation efforts without more money.

“We have to exhaust our limited domestic budget to finance our adaptation efforts, taking away from other priority areas such as healthcare and education,” she told Grist.

The country has used huge amounts of reclaimed land to build quasi-artificial islands that can house displaced populations from lower-lying isles.

The capacity issue is especially acute for island nations with small populations, who don’t always have the infrastructure needed to navigate the complex bureaucracy of the multilateral U.N. funds that support adaptation. These low-lying nations often face an almost existential threat from rising sea levels, so they won’t necessarily benefit from just one capital project paid for by these funds — they have to adapt their entire territories in order to survive.

“By the time all these little things have happened for you to get the money, the risks have increased,” said Filomena Nelson, an adaptation negotiator from Samoa who works for the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme, an intergovernmental authority that manages environmental protection across Pacific islands. “It takes forever, it’s complicated, it’s a vicious cycle.”

When negotiators can’t discuss money, adaptation talks tend to get mired in the realm of the abstract. This was evident in Baku this week, where negotiators in one adaptation talk confronted a multi-dimensional graph about “transformational adaptation” with three axes: “time,” “changes in paradigms,” and “changes in the fundamental attributes of socio-ecological systems.” That chart was accompanied by another evaluation matrix that resembled a Rubik’s cube. One observer joked that she wanted to get it printed on a shirt.

In the meantime, the need for action is only getting more urgent.

The United Nations’ annual report on adaptation, which became public just before COP29 began, underscored the life-or-death stakes of an issue that often feels like a forgotten middle child at global climate talks. The U.N. expert who led the report introduced it by saying that “people are already dying, homes and livelihoods are being destroyed, and nature is under assault.” The report estimated the unmet need for adaptation investment at up to $359 billion every year. Notably, this need was not expressed in forested acres or boreholes drilled, but in U.S. dollars.

In recent years, as developed countries have belatedly endorsed the idea of a fund for redressing climate-fueled damage — and as the world has verged on breaching the 1.5 degrees C threshold laid out by the Paris accord — some have started to discuss the demise of small island states as an inevitability rather than a possibility. But Nelson said that while some disaster losses are inevitable, Samoa and other countries aren’t ready to admit that they will have to leave their homelands, an outcome that many experts fear will be likely with 1.5 degrees or more of warming.

“We will not give up our land just because we’re facing these issues,” she said. “This is where we come from — if we give up now, it sends the wrong signal.”